Although the claim by a UK researcher that he identified Jack the Ripper from a semen stain on an 130-year-old shawl is drawing derision, new forms of DNA analysis mean old letters, pipes, and locks of hair may be ready to shed their secrets.

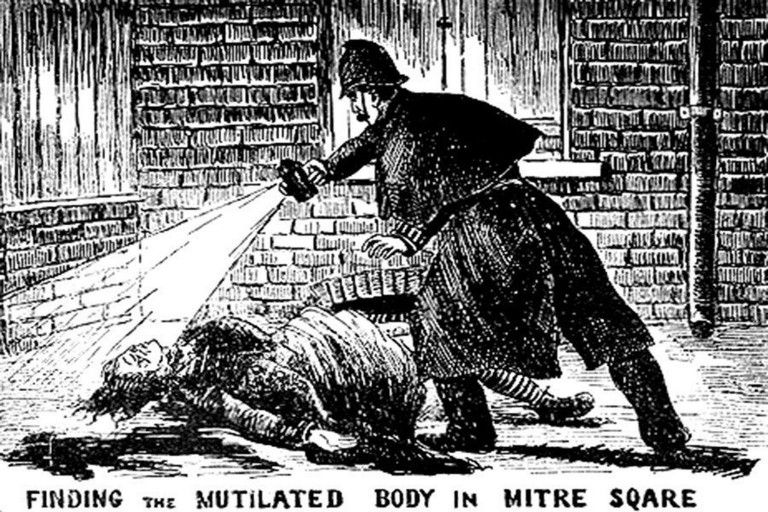

London killer: According to a paper in the Journal of Forensic Sciences, a researcher says DNA obtained from what he calls the “only piece of physical evidence” linked to the infamous Victorian-era killings may belong to a Polish immigrant and longtime suspect, Aaron Kosminski.

Experts are doubtful. On Twitter, journalist and geneticist Adam Rutherford called the report “terrible science” and bad history, too, since the shawl’s provenance is suspect.

Old objects: What is real is a nascent industry specializing in extracting DNA from artifacts, such as stamps licked by Grandpa and antebellum tobacco pipes buried on former plantations.

If researchers manage to get a DNA sample, they be able to learn something about what our ancestors were doing, who they were, even their hair and eye color.

Famous DNA: While it remains a tricky business to extract DNA from old letters, some companies are offering to do it. TotheletterDNA, based in Queensland, Australia, says it will try to look for and test DNA left behind on stamps and envelopes for about $550.

Gilad Japhet, founder of the ancestry DNA testing company MyHeritage, claimed at a conference last year that he has letters written by Albert Einstein and Winston Churchill and is trying to obtain DNA from them.

“Maybe our ancestors did not realize it,” Japhet is quoted in The Atlantic as saying, but “when they were licking those stamps and the envelope flaps, they were sealing their precious DNA for you forever.”

Zodiac Killer: According to the Sacramento Bee, police are now getting into the artifacts game by analyzing envelopes that the Zodiac Killer used to send cryptic messages to several newspapers in the 1960s. While the serial murderer was careful to escape detection, he probably didn’t realize that licking an envelope could give him away, since DNA testing wasn’t yet widely used at that time.

Privacy questions: Once police or curious researchers have some DNA, they can use genetic genealogy to zero in on who it belongs to. That’s most often done by uploading the information to an open-source website of DNA profiles called GEDMatch, where it’s possible to locate relatives on the basis of genetic information.

The company that operates GEDMatch says it allows researchers working with old DNA from an object free access, so long as the “previous owner or user of the artifact is known to be deceased.” For now, the company doesn’t want you testing contemporary objects—say, to learn who has been sticking gum under the desk—but that could be next.