Business Impact

What Technologies Will Crowdfunding Create?

Super-users, hobbyists, and gadget fans are investing in innovations they want, and creating a new generation of entrepreneurs along the way.

It’s becoming a common story. A project listed on Kickstarter, the Internet crowdfunding website, ends up wildly exceeding its financial goals. Suddenly, someone is in business.

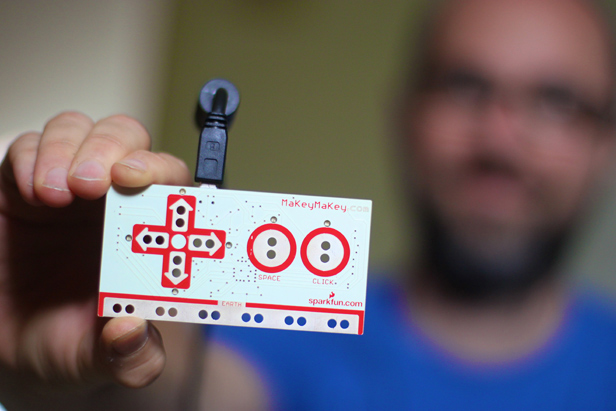

That’s what happened to inventor Jay Silver, creator of MaKey MaKey, an “invention kit” consisting of a processor board and alligator clips that turns objects with high electrical resistance—bananas, Play-Doh, human flesh—into computer controllers. Silver listed the project on Kickstarter this year hoping to raise $25,000. He ended up with $568,106.

Since then, it’s been a race to negotiate with Chinese manufacturers, customs agents, and wholesalers to produce and ship what will be the first product of Silver’s newly incorporated company, JoyLabz. “I was going to start this company in a few years, but my crowdfunding success accelerated the timing,” says Silver, who is 33.

In the U.S., Internet funding occurs on Indiegogo, GoFundMe, and similar websites that permit people to donate money to projects, including films and journalism. Often they’re promised something in return, like a T-shirt or movie ticket. Silver and his partner, Eric Rosenbaum, promised MaKey MaKey kits to anyone who gave them $35; they ended up getting donations from 11,124 people.

Crowdfunding is supporting inventions which might otherwise have limited economic prospects, including gadgets appealing to narrow markets, hobby kits, and a 4,000-pound spider robot that can seat two (see “10 Emerging Technologies: Crowdfunding”). Perhaps most of all, it has become a fertile outlet for self-described “makers” such as Silver, who says his goal is to create “a more democratic world where everyone modifies their own space.”

Makers are a breed of super-hobbyists who have been coalescing into a social movement around technologies like 3-D printing. Because of the availability of crowdfunding, their projects are becoming more ambitious, and some are turning into companies. One project called Ninja Blocks—the invention is a rubbery block of sensors that uploads reports to the Internet—raised $102,000 on Kickstarter, generating attention that allowed its creators pull in another $1 million from investors.

“The business side of the maker movement is hockey-sticking right now,” says Silver, who recently took a day job as “maker research scientist” at Intel’s Interaction and Experience Research Laboratory, the first person to hold that title. “I don’t know if people realize that. If you have a good idea, there is nothing stopping you from doing it, including the funding.”

Crowdfunding is working best where existing funding models are failing. Some video game designers, for instance, have turned to crowd sites to bypass the Hollywood studio–like system of game publishers, who invest heavily in just a few blockbuster titles.

“It’s forcing a model of new ways of funding into area where the funding methods have been static and somewhat broken,” says Ethan Mollick, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, who has studied Kickstarter. “Crowdfunding is not the solution for your next clean-energy project. But there are a lot of smaller innovations that could end up being world-changing, and a lot of entrepreneurs being created.”

Owing to changes in U.S. securities regulations, starting next year entrepreneurs will be able to sell shares to the public over the Internet, a concept being called “equity crowdfunding.” Companies will be able to raise as much as $1 million per year from the public. Individuals, for the most part, will be allowed to invest up to 5 percent of their income. The rule changes are expected to lead to a significant increase in crowdfunding, which by one estimate totaled about $1.5 billion globally in 2011, some of it for social causes.

While some investors will be in it for money, the riskiness of investing in startups is likely to mean that equity crowdfunding ends up resembling the donation model, says Nicholas Tommarello, CEO of WeFunder, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, company developing a commercial crowdfunding portal. He says bars, bakeries, and technologies that are fun or solve social problems are likely to be popular categories.

“People want to give back, see progress, live vicariously, and learn something,” says Tommarello. “Enterprise software to help logistics companies save 10 percent probably isn’t going to work.”

Much of the money may flow to what are known as “user innovators”—people who invent products they need or want, initially for their own use. (In the most famous case, Tim Berners-Lee invented the Web as an improvement on the Internet.) A study by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation released in February estimated that 47 percent of startups pursuing innovative products had been created by people who fit this profile (the full report is here).

“A lot of breakthroughs are created by product users, not in centralized R&D labs. And crowdfunding will be a new way to pay for that,” Mollick says. By raising money over the Internet, companies will simultaneously get financing, discover how large their markets are, and connect to advanced users who will be their first customers.

That is what happed to Silver, who initially turned to Kickstarter because he’d been making MaKey MaKey circuit boards by hand while completing graduate work at MIT’s Media Laboratory. He needed a larger supply to use in academic workshops and show off at hobbyist gatherings known as Maker Faires. With 800 pre-orders, he learned, he could get a much lower price from SparkFun, the company in Colorado that agreed to manufacture the first run.

MaKey MaKey is mostly an entertainment device—Silver calls it an art form—that can be used to, for instance, make alphabet soup letters into a functioning keyboard. The system could have commercial uses, too, in such tasks as creating rapid prototypes of a push-button computer interface, like an ATM screen or interactive museum display.

This summer, Silver shifted manufacturing to China, and several thousand more MaKey MaKey kits have since arrived. They will be sold as do-it-yourself gifts in online stores like Uncommon Goods and ThinkGeek, as well through a website created by Silver.

Silver says his company is now in a position to work on other projects, including an iPhone app that would help the user achieve higher states of consciousness. That may sound crazy, but Silver says it will depend on what the crowd thinks. “If I have a good idea that is recognized as such, I don’t need to sell a CEO on it,” he says. “If there are a thousand people who think that a thing should come into the world, then we are done. Then it will come into the world.”