How Authors Write

The technologies of composition, not new media, inspire innovations in literary styles and forms.

Early in Nicholson Baker’s slim first novel, The Mezzanine (1988), whose entire action takes place during an escalator ride at lunchtime, the narrator describes buying milk and a cookie, and then pauses to consider, in a page-long footnote, the “uncomfortable era of the floating drinking straw”:

I stared in disbelief the first time a straw rose up from my can of soda and hung out over the table, barely arrested by burrs in the underside of the metal opening. I was holding a slice of pizza in one hand, folded in a three-finger grip so that it wouldn’t flop and pour cheese-grease on the paper plate, and a paperback in a similar grip in the other hand—what was I supposed to do? The whole point of straws, I had thought, was that you did not have to set down the slice of pizza to suck a dose of Coke while reading a paperback.

Baker speculates about how the straw engineers had made “so elementary a mistake,” designing “a straw that weighed less than the sugar-water in which it was intended to stand”; pardons the engineers who had forgotten to take into account how bubbles of carbonation might affect a straw’s buoyancy; explains how such unsatisfactory straws came to be sold to restaurants and stores in the first place; and, in a kind of musical resolution, concludes by remembering the day when he noticed a plastic straw, “made of some subtler polymer,” once again anchored to the bottom of a soda can.

The point of this footnote and 49 like it is to subject everyday objects to such close attention that they will, in the words of Sam Anderson in the Paris Review, “start to glow with significance.” Justifying the footnotes (in another footnote), Baker writes that “the outer surface of truth is not smooth, welling and gathering from paragraph to shapely paragraph, but is encrusted with a rough protective bark of citations, quotation marks, italics, and foreign languages, a whole variorum crust of ‘ibid.’s’ and ‘compare’s’ and ‘see’s’ that are the shield for the pure flow of argument as it lives for the moment in one mind.”

The Mezzanine

Nicholson Baker

Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1988

“Host”

David Foster Wallace

from Consider the Lobster

Little, Brown, 2005

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Laurence Sterne

R. and J. Dodsley, 1759–1767

On the Road

Jack Kerouac

Viking, 1957

The Emigrants [Die Ausgewanderten]

W. G. Sebald

Vito von Eichborn, 1992

A Visit from the Goon Squad

Jennifer Egan

Alfred A. Knopf, 2010

Writers had used short footnotes for artistic effect before The Mezzanine (Borges, for one, had employed them as dusty jokes). But when Baker told Anderson that “nobody was doing footnotes back then,” he was plausibly laying claim to an innovation: footnotes so long and involved they drowned the narrative, so that the reader, like a disoriented swimmer, would surface at the note’s termination, spluttering, “Where am I?”

How did Baker invent such a literary device, which afterward grew to overluxuriant complexity in the writings of David Foster Wallace and his imitators (including the infamous “Host,” which is mostly footnotes, and where Wallace attempted a footnote to a footnote to a footnote)?

As it happens, we know. Baker says he wrote The Mezzanine on an early portable computer called the Kaypro, “a really lovely machine” with “two floppy drives” that “looked like a small . . . piece of medical equipment.” He had always loved footnotes; the Kaypro’s word processing program made it easy to insert and format them. A typewriter would have placed natural limits on the length of a footnote. Had the thought occurred, a very determined Baker might have added long footnotes by re-creating Proust’s “paperoles,” those additional sheets of paper that the French writer glued to the manuscript of À la recherche du temps perdu in order to elaborate endlessly upon his characters. But the Kaypro invited expansiveness, and Baker accepted. Wallace and others followed, performing similar tricks with the software they used.

At a time when new media are proliferating, it is tempting to imagine that authors, thinking about how their writing will appear on devices such as electronic readers, tablet computers, or smartphones, consciously or unconsciously adapt their prose to the exigencies of publishing platforms. But that’s not what actually happens. One looks in vain for many examples of stories whose style or form has been cleverly adapted to their digital destinations. Stories on e-readers look pretty much as stories have always looked. Even The Atavist, a startup in Brooklyn founded to publish multimedia long-format journalism for tablet computers, does little more than add elements like interactive maps, videos, or photographs to conventional stories. But such elements are editors’ accretions; The Atavist’s authors have not been moved, as Baker was, by the creative possibilities of a new technology. Writers are excited to experimentation not by the media in which their works are published but, rather, by the technologies they use to compose the works.

There have been odd exceptions, of course. In Tristram Shandy, published from 1759 to 1767, Laurence Sterne employed all the techniques of contemporary printing to remind readers they held a book: there is a black page that mourns the death of a character, a squiggly line drawn by another character as he flourishes his walking stick, and on page 169, volume 3, of the first edition a leaf of paper marbling, a type of decoration that 18th-century bookbinders offered their wealthier clients. With this technology, pigments are suspended upon water or a viscous medium called “size,” creating colorful swirls, and are then transferred to a paper laid by hand upon the liquid. Each copy of the first edition of Tristram Shandy thus included unique marbling; the process was so expensive and time-consuming that later editions printed a monochrome reproduction instead. Sterne, an eccentric and tubercular Anglican priest, badgered his publisher, Dodsley, to include the page (which he called “the motley emblem of my work”) in order to suggest something about the opacity of literary meaning.

Yet such responses to publishing technologies are rare. Besides the way Baker and Wallace used the “Insert Footnote” function in word processing software, writers have more often found inspiration in typewriting, photocopying, blogging, and, most recently, presentation software such as Microsoft PowerPoint and social media like Twitter.

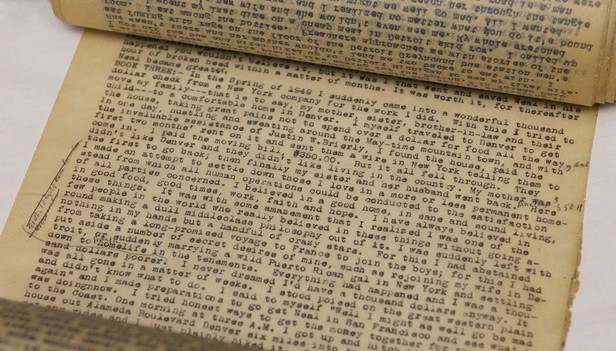

Jack Kerouac claimed to have written On the Road in 1951 during a three-week, Benzedrine-fueled delirium of “spontaneous prose,” typing continuously onto a 120-foot roll of teletype paper. In reality, he worked from dozens of small notebooks kept during his years on the road with Neal Cassady, typed on a homely roll created by taping together sheets of tracing paper, and revised the scroll’s text at leisure; but his first draft really was produced without paragraph breaks on a continuous roll of paper. (The scroll still exists—except for its final section, where Kerouac laconically scrawled, “Ate by Patchkee, a dog”—and is on display at the British Library in London until the end of the year.)

If the physical artifact of the scroll is astonishing to see, the prose it made is celebrated for its ecstatic lyricism. It was a tremendous influence on Allen Ginsberg and all the Beat writers who wanted a jazzy style commensurate with the manic energy of postwar America:

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, and all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear?

Tools of typing are not the only technologies of composition that can inspire. The German writer W. G. Sebald composed strange meditations, neither obviously fiction nor nonfiction, about the terrible events of the 20th century. He once said of the Holocaust that “no serious person thinks of anything else,” but he approached the subject obliquely. His books begin quietly (“At the end of September 1970, shortly after I took up my position at Norwich, I drove out to Hing-ham in search of somewhere to live,” and “In the second half of the 1960s, I traveled repeatedly from England to Belgium”) but pursue a deteriorating orbit around the central tragedy, like a satellite falling into a sun. The Emigrants (in German, Die Ausgewanderten), published in 1992, seems a straightforward account of the blighted lives of four Germans in exile; only gradually does the reader sense all the missing, those who never escaped but died. In Austerlitz (2001), Sebald feels his way through the life of the eponymous hero, brought to England in 1939 aboard a Kindertransport, raised by adoptive Nonconformist parents in Wales, who, late in life, returns to Prague and Paris in order to learn the fate of his biological parents.

The books are notable for their formal qualities: virtuosic digressions, descents into the past through nested narrators, and convoluted sentences that extend over many pages. Most idiosyncratic of all is Sebald’s use of uncaptioned, grainy black-and-white photographs. Some are clippings from newspapers and magazines; others are snapshots, taken with Sebald’s little Canon camera; others are of buildings, presumably destroyed in the Allied bombing, and many more of people, also presumably lost. The photographs have the melancholy air of found art; but while the author implies that some of the photos were found in his family’s photo albums, he does not say which. After Sebald died in a car crash in 2001, the Guardian’s obituary recalled how he constructed his books at the University of East Anglia, in England, where he was a professor of European literature: “He was an exacting customer at the University’s . . . copy shop, discussing what might be done with his images, adjusting the size and contrast.” Sebald is really inimitable; but that has not stopped hundreds, including Will Self, from trying, so that “Sebaldian” (which mostly means a mournful combination of long sentences and photographs) has become a critics’ adjective.

Even when a writer’s style is informed by a publishing platform, it’s more often because that technology is also an authoring tool: blogging programs, such as Movable Type or WordPress, are content management systems that publish blogs to the Web, but they are also sophisticated word processors that make it easy to link to other blogs, use block quotes, or embed photographs and videos. The distinctive voice of modern bloggers—impulsively reactive, colloquial, intimate, allusive, and, above all, chatty—owes much to such software. Emily Gould, who has contributed to MIT Technology Review, is as responsible as anyone for the reigning style. In 2006, her blog, Emilymagazine, was noticed by the editors of Gawker, who hired her to write gossip about other young people working in media in New York. She was funny, acute, and oversharey; she became a microcelebrity and found her manner and coinages aped by other bloggers. Gould soon left Gawker tired of gossip, and became more circumspect, but she is still funny. A not untypical post on Emilymagazine, from 2010, begins:

While researching a This Recording post about how Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash’s love affair affected their respective artistic outputs—because, I guess, I have assigned myself to be the Us Weekly of 40 years ago?—I fell into a YouTube odyssey of Graham Nash’s British Invasion band The Hollies, specifically, an odyssey of iterations of this song, Carrie-Anne.

The sentence is packed: preceded by an embedded video, it self-referentially links to another post, alludes to shared assumptions about celebrity magazines, parodies the modern-girlish habits of self-deflation and what linguists call “high rising terminals” (where pitch rises to a kind of pseudoquestion), and introduces the subject of the post, a saccharine example of ’60s pop.

A recent example of how authoring tools can suggest novel styles of writing can be found in Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, which won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The novel, a collection of 13 interconnected short stories, describes the depredations of time (the goon squad of the title, because “time’s a goon”) upon a cast of characters who first meet in San Francisco’s punk scene in the late 1970s. Chapter 12, “Great Rock and Roll Pauses,” is written in the form of a series of Microsoft PowerPoint slides (complete with bullet points, Venn diagrams, and other infographics) and presented as the creation of Alison, the 12-year-old daughter of one of the protagonists. Ally resorts to -PowerPoint because it is her native idiom; but Egan obviously delighted in overcoming the artificial constraints of the format in order to tell the simple story of a girl’s relationship with her autistic brother and his pathetic obsession with musical pauses. (The author has posted Ally’s slides with their accompanying music on her website.)

Egan continues to be inspired by technologies of composition. Last spring, she published a short story on the New Yorker’s twitter account, @NYerFiction, entirely in the form of tweets. The story, “Black Box,” was later printed in an issue of the magazine devoted to science fiction. Egan has explained that she wanted to write a story that would seem to be told inadvertently, using a narrator’s notes to herself: “My working title for this story was ‘Lessons Learned,’ and my hope was to tell a story whose shape would emerge from the lessons the narrator derived from each step in the action, rather than from descriptions of the action itself.” In the story, a “beauty,” a spy working in the south of France to seduce and collect intelligence from a repellent “Designated Mate” and his colleagues, records a mission log that she and her fellow beauties might later find helpful. Because the logs are silent self-communings, and because she is alone, the overwhelming impression is of the narrator’s vulnerability and bravery:

The first thirty seconds in a person’s presence are the most important.

If you’re having trouble perceiving and projecting, focus on projecting.

Necessary ingredients for a successful projection: giggles; bare legs; shyness.

The goal is to be both irresistible and invisible.

When you succeed, a certain sharpness will go out of his eyes.

Egan, Gould, Sebald, Kerouac, and Baker were all writing in eras when new media were everywhere, but what computer scientists call “platform shift” did not get their juices going. The technologies of composition did. Why this should be so is not mysterious. The explanation is that literary writers are solitary creatures: their days are spent alone, with keyboards and pens under their fingers and a humming photocopying machine down the road at the university. Those things are real, and what one can do with them exciting, while websites, e-readers, and even books seem abstractions, mere mechanisms of distribution.

Jason Pontin is the editor in chief of MIT Technology Review.