You Can Now 3-D Print a Toupee

Researchers have figured out how to use a 3-D printer to make plastic hair of varying thicknesses for things like toys and brushes.

In a pinch and need a new paintbrush, or perhaps a hairpiece?

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have come up with a method for using 3-D printers to fabricate plastic hair—a technique they call “furbrication” that’s similar to what happens when you pull a hot glue gun away from an object it has been touching.

Typically, 3-D printers take a substrate like metal or plastic and add one layer on top of another, following the instructions of a model made with modeling software, to build an object like a chess piece.

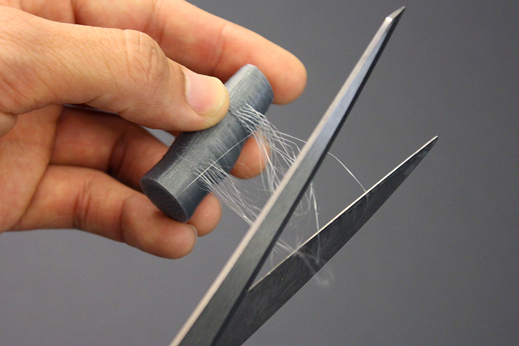

To create the hair, the researchers, led by graduate student Gierad Laput, instruct the printer head—which is the part of the 3-D printer that layers the substrate—to dot the surface of a model with a little ball of melted plastic. Then, instead of adding another layer as it usually would, the printer head pulls away. As it does, a thin, soft string of plastic forms between the printer head and the model’s surface.

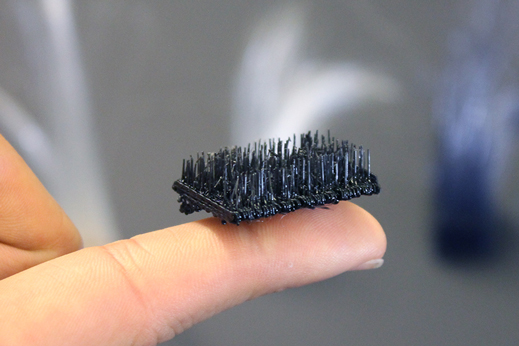

When this is repeated over and over, as this video the researchers made demonstrates, a clump of hair, fur, or brush bristles forms; length and thickness are ultimately determined by how fast and far away the printer head pulls from the surface. A paper on the work will be presented in November at a conference in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Today, 3-D printers can cost as low as a couple hundred dollars. This has opened up the potential for people to design and manufacture objects, from garden gnomes to jewelry, right from their garage. But in comparison to what makers hope 3-D printing will be capable of—printing circuit boards or replacement bones, for instance—it still has a long way to go.

Given that, Laput hopes this technique will make it possible to 3-D print things as frivolous as troll dolls with wavy hair and as useful as brushes and perhaps a form of Velcro.

Laput says that folks who already have a 3-D printer—even a cheap one—can do this at home by using add-ons for modeling software that the group developed, which let users specify the type of hair.

The group used PLA plastic, one of the cheapest and most basic additive printing substrates. The hope is to someday use something more complicated, like metal, which Laput believes would lead to even more applications.

“You can imagine hair that has magnets,” he says.