The Frontline Reporter

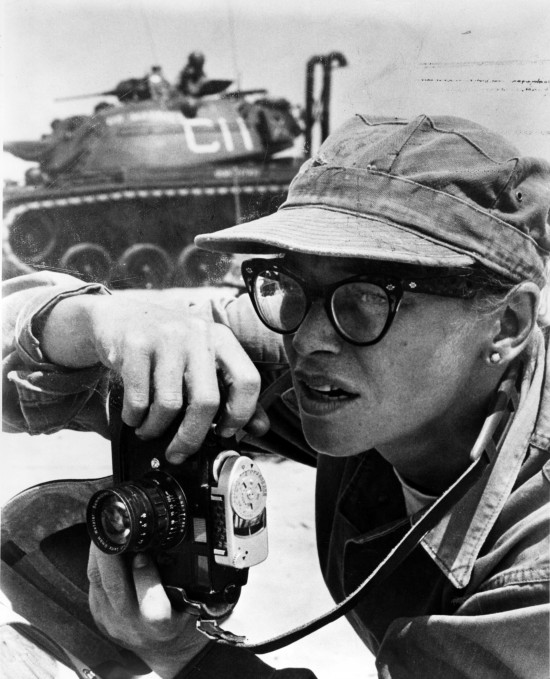

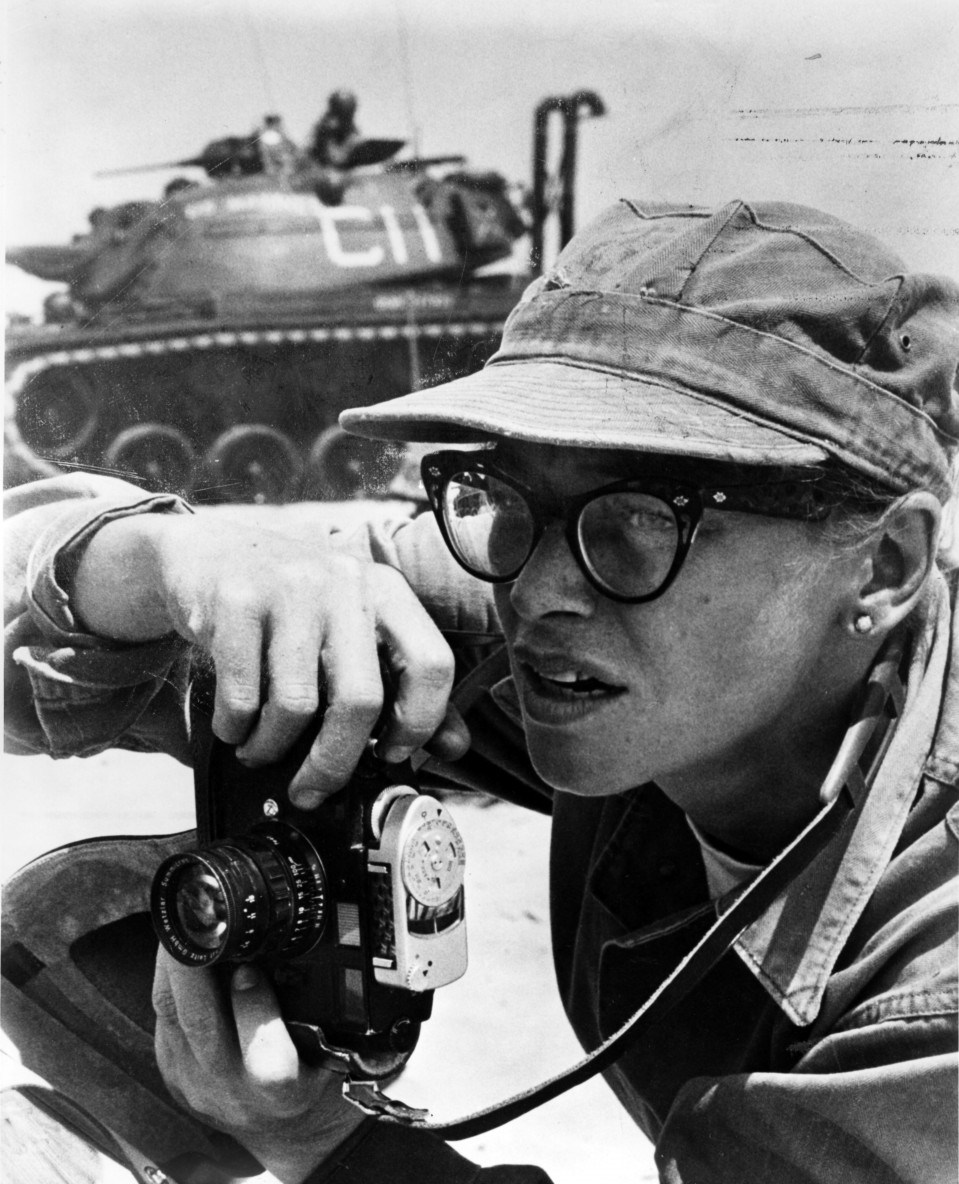

Dickey Chapelle ’39 blazed a trail for combat photojournalists.

Georgette “Dickey” Chapelle ’39 had been a credentialed war correspondent for nearly three years before she finally got a chance to cover combat, in 1945. Sent to a hospital ship to take photos of wounded soldiers evacuated from the U.S. assault on Iwo Jima, the small woman with the large Speed Graphic camera managed to get ashore to witness the fighting. When she reached the front, she didn’t at first realize that the “insects” she heard flying past her head were sniper’s bullets—or that she was the target.

Chapelle’s journey to the front lines began with a two-year stint at MIT, where she’d enrolled after deciding to become an aerial explorer like Admiral Richard “Dick” Byrd, whose nickname she decided to adopt. One of only seven women admitted in 1935, she had entered the Institute as Dickey Meyer, a 16-year-old aeronautical engineering student. While living in Boston, she gravitated toward the Charlestown Navy Yard and local Coast Guard bases and hung out with seaplane pilots, which led to the sale of her first story to the Boston Traveler. But the start of her journalism career marked the end of her academic career. Having missed too many classes and earned low grades, she was asked to leave MIT after her second year.

She went on to do publicity writing for the aviation industry and marry photographer Tony Chapelle, and when he rejoined the Navy after Pearl Harbor, she became a war correspondent. A month after covering Iwo Jima, she became the only female photographer assigned to the invasion fleet anchored off Okinawa in the bloodiest battle of the war in the Pacific. In spite of direct orders not to go ashore, Chapelle went anyway. The first general she came across told her driver, “Get that broad the hell out of here.” Eventually she made her way to the U.S. Marines Sixth Division command post, where Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd granted her permission to travel with a medical unit.

Chapelle covered combat operations for 10 days before the Navy caught up with her and pulled her off the island, withdrawing her military press credentials. She was sent home.

When the war ended, she worked at Seventeen magazine as a staff photographer and associate editor and then traveled extensively with her husband throughout Europe and the Middle East, documenting the rebuilding of the postwar world for the American Friends Service Committee, CARE, and other relief agencies. After their 15-year marriage ended, Chapelle contacted Shepherd, by then a four-star general and the commandant of the Marine Corps, who helped her obtain military press accreditation in 1955.

For the next decade, Chapelle covered wars around the world, including the Hungarian uprising, the war in Algeria, and the Cuban revolution. On assignment for Life magazine, she was arrested by Russian soldiers as she helped deliver penicillin to Hungarian refugees fleeing into Austria. Accused of being a spy, she was interrogated by the Hungarian secret police, threatened with execution, and held for nearly two months in Budapest’s notorious Main Street Prison, also known as the “house of terror,” before being released.

Chapelle went to Vietnam in 1961 and reported on U.S. forces advising South Vietnamese troops near the border with Laos. Some of this work appeared in a 1962 photo essay in National Geographic, which included her photo of a U.S. Marine manning a machine gun at a helicopter door, revealing for the first time that U.S. advisors were doing more than merely advising Vietnamese troops. That photo was named the 1963 Picture of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association. She also received the Overseas Press Club’s George Polk Award in 1962 for her Vietnam reporting.

On her fourth trip to Vietnam, in November 1965, Chapelle was covering Operation Black Ferret, a Marine search-and-destroy mission, when a Marine lieutenant walking just ahead of her tripped a booby trap. A spray of shrapnel wounded five Marines and a Navy corpsman and killed Chapelle. She was the first American female war correspondent to die while covering combat operations.

The following year, U.S. Marines named a field hospital in Vietnam in her honor. At the dedication, Lieutenant General Lewis Walt recalled what she had told him at dinner the night before she died: “When my time comes, I want it to be on a patrol with the Marines.” Five decades later, Dickey Chapelle was named an honorary Marine. —John Garofolo

A veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom, John Garofolo is the author of Dickey Chapelle Under Fire: Photographs by the First American Female War Correspondent Killed in Action. See some of Chapelle’s photos (and a few of Chapelle herself) below.