Getting to 2°

Emotions (and temperatures) run high in a mock climate negotiation.

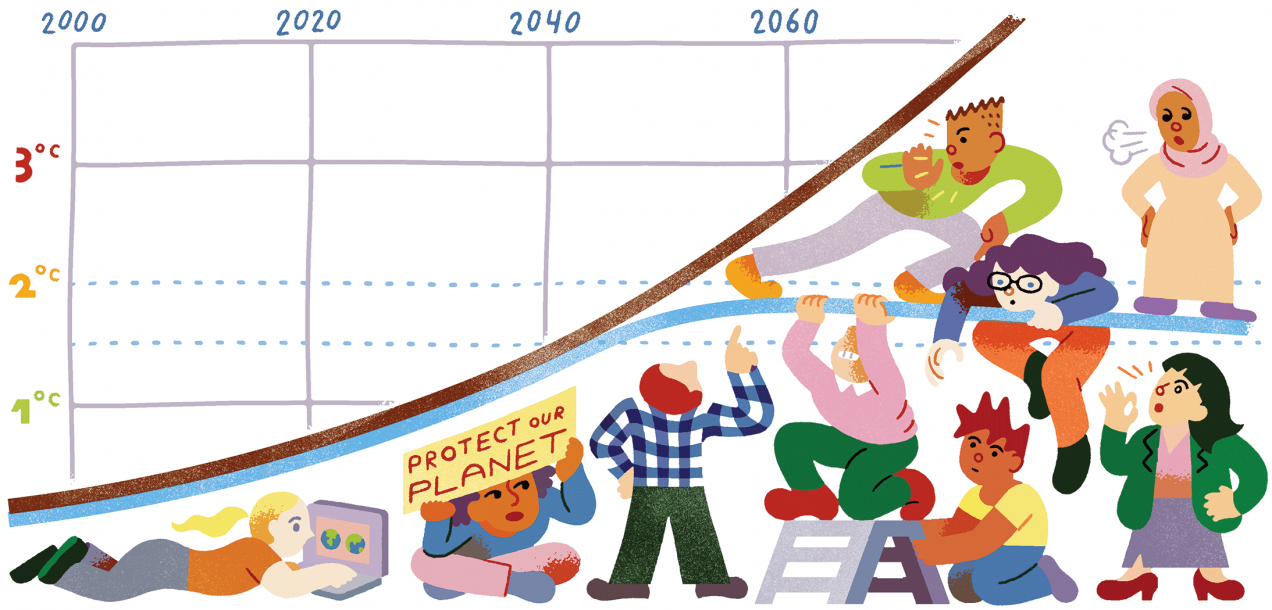

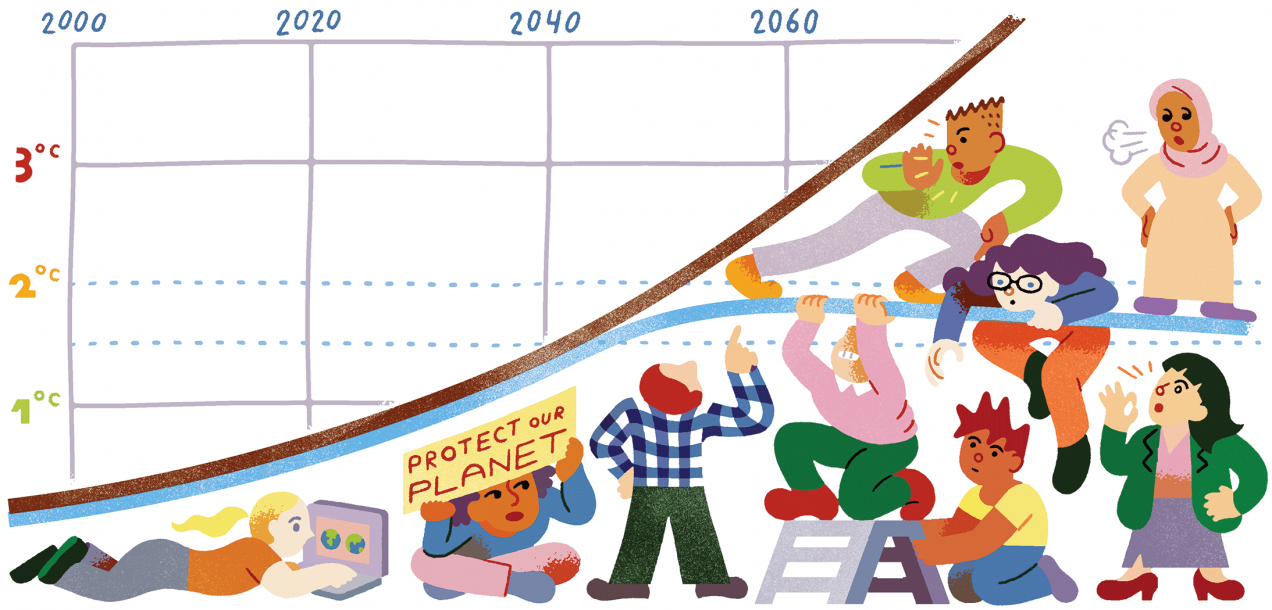

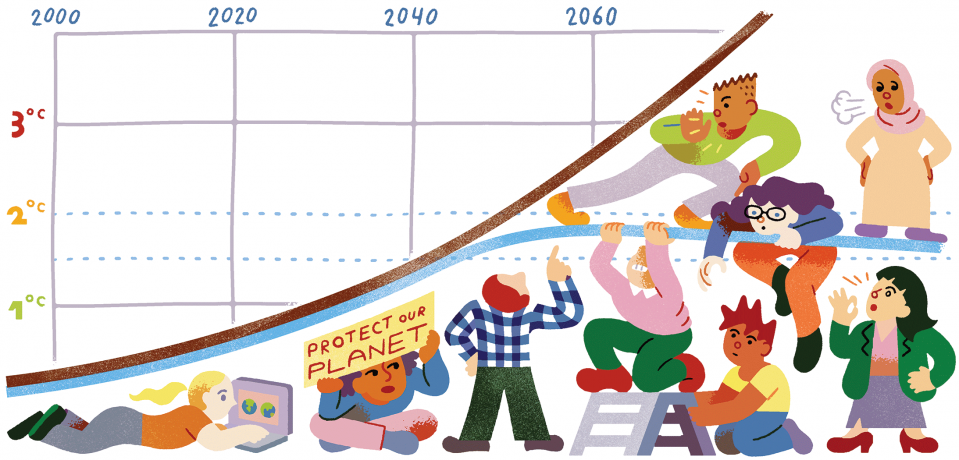

A deep chorus of boos erupts and empty water bottles are lobbed at the podium as the man behind it announces that the United States will contribute nothing to the Green Climate Fund. When the Chinese representative takes the floor and declares that his nation will stop increasing its emissions—by 2070—he is met with incredulous laughter. The first round of climate negotiations draws to a close as the emissions, forestation, and funding commitments of each delegation are tallied on a whiteboard. The delegates’ goal is to keep temperature rise to 2 °C over preindustrial levels. Their commitment data is entered into a climate simulator, which projects the result onto a large screen: the expected average temperature will rise 3.6° by 2100.

This is World Climate Simulation, a negotiation exercise that uses a simulator to show participants the outcomes of their decisions in real time. It’s led by Sloan professor John Sterman, PhD ’82, and Andrew Jones, SM ’97, of Climate Interactive; the pair developed the exercise and simulator, known as C-ROADS, over a decade ago to make climate learning visceral. “New information doesn’t change thinking on climate,” Jones says. “New experiences do.”

The 55 participants, who hail from 17 countries and are taking Sterman’s business dynamics course for executives, form nine delegations. Six represent nations or blocs with an official voice in the negotiations. Climate activists and the fossil-fuel industry are also represented—as are U.S. states and cities committed to upholding the Paris Agreement—but only have the power to influence, not to make formal commitments.

In the first round, climate activists shut off the lights and circulated with protest signs, shouting “Shame!” at the wealthier countries. Accusations of hypocrisy led to heated arguments between developed and developing nations. Some delegates attempted to negotiate with the United States, but most rushed to China’s crowded table instead. (“That’s new,” Jones said.)

Sterman now walks through the outcome: side-by-side graphs show that even as emission rates level off, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels keep increasing because the greenhouse gas is still entering the system about twice as fast as it’s absorbed by plants, soil, and oceans. Opening a sea-level map, Sterman zooms in on south Florida amid quips about Mar-a-Lago. Blue pixels eat away at the coastline as the model shows how the water would rise in this scenario. When he adds storm surges to the equation, the room falls silent. A wide swath of blue fills the peninsula. “You have total devastation,” Sterman says.

Demonstrating sea-level changes in Shanghai elicits a collective gasp. “It’s the same worldwide,” he says. A heaviness descends on the room. But developed countries and the fossil-fuel industry together pledge $190 billion to help developing nations transition to cleaner technologies. China moves its emission stabilization date up to 2030, to hearty applause. Two hours into the simulation, the participants are on the edge of their seats as the new commitments are entered into the simulator. Total temperature rise: 2.3°.

“You’ve created a much safer world,” Sterman says.

Advertisement