Biotechnology / CRISPR

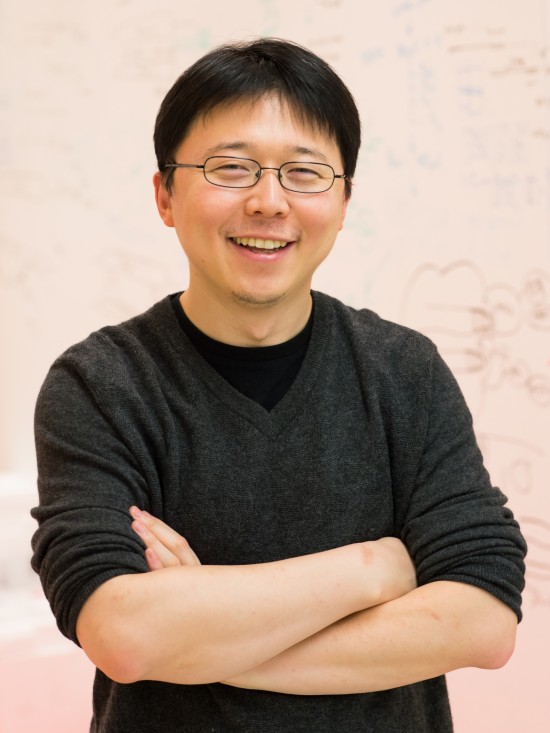

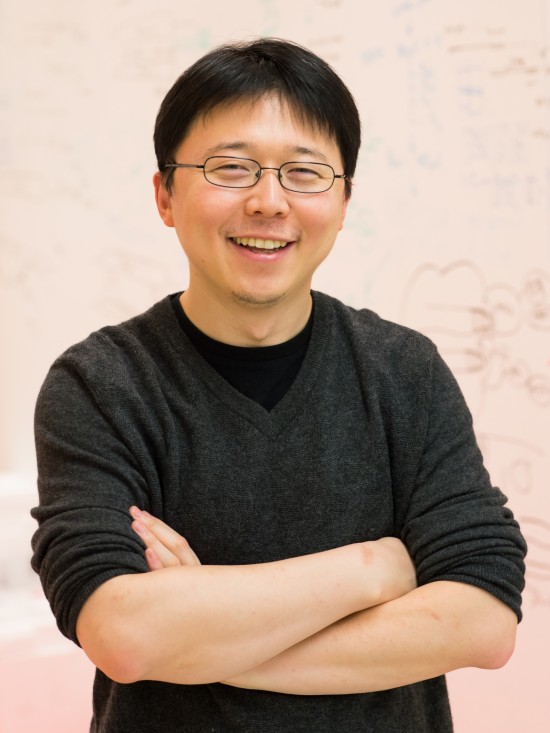

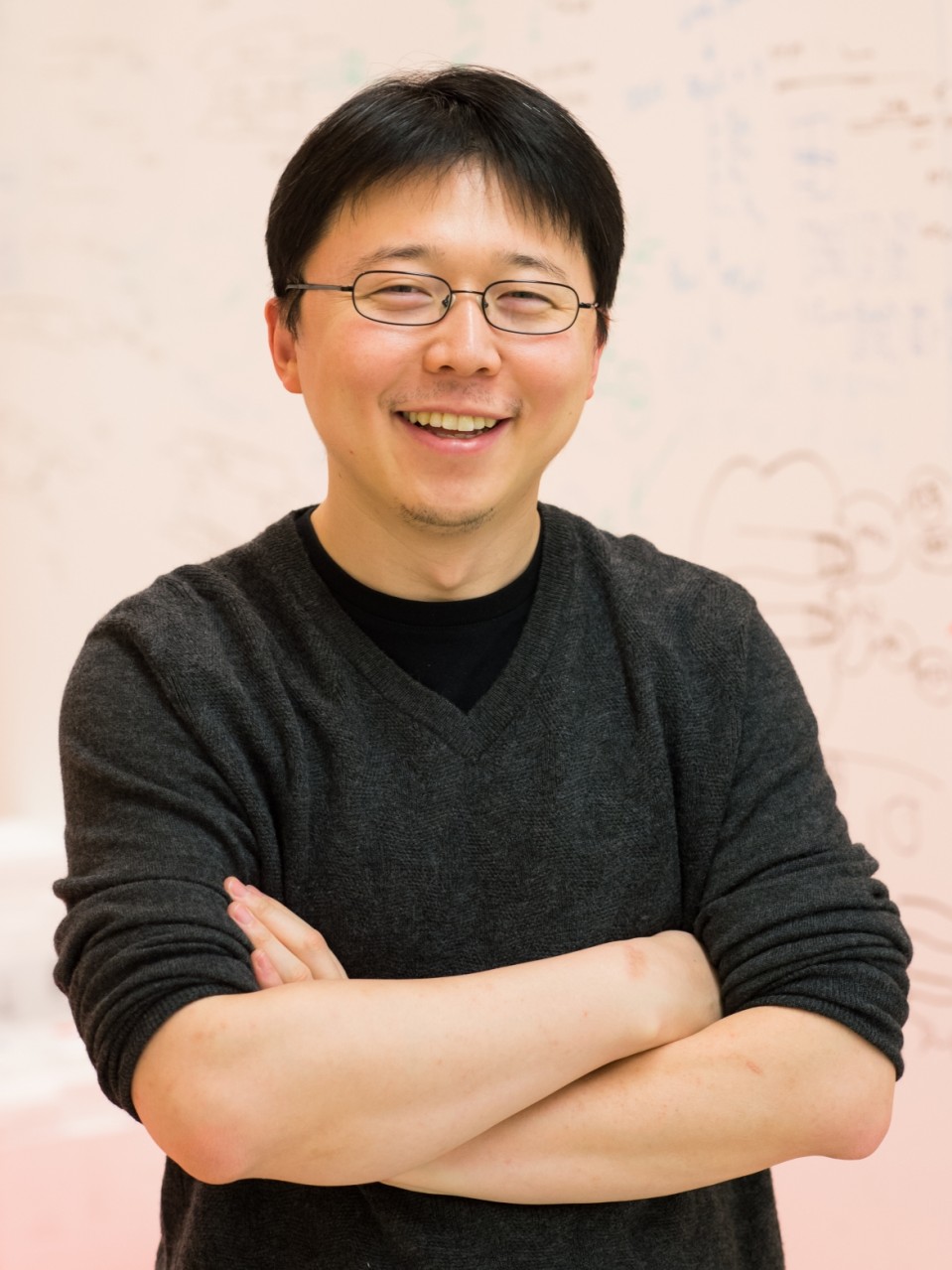

CRISPR inventor Feng Zhang calls for moratorium on gene-edited babies

A leading scientist wants Chinese researchers to halt a project to create genetically modified children.

Feng Zhang, one of the inventors of the gene-editing technique CRISPR, has called for a global moratorium on using the technology to create gene-edited babies.

The call from Zhang, a member of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, comes a day after a Chinese researcher claims to have created twin girls with modified genes to make them resistant to HIV.

“Given the current state of the technology, I am in favor of a moratorium on implantation of edited embryos,” Zhang said in a statement provided to MIT Technology Review.

The researchers in the Chinese trial edited human embryos to remove a gene called CCR5, which they said would make the children resistant to HIV. The study was carried out in secrecy, however, and medical experts question whether it was necessary or safe.

Zhang said the risks of the experiment outweigh the benefits and said he was “deeply concerned” that the Chinese project was undertaken in secrecy.

Previously, academic bodies including the US National Academy of Sciences have said genetically modified children should be made only under strict conditions of safety and oversight.

Feng’s call for a complete moratorium comes the day before a major genome-editing summit being held in Hong Kong. The Broad Institute said Zhang was on a flight heading to the conference and was unable to comment further.

In 2013, Zhang was first to show how the CRISPR tool could be used to edit DNA in human cells, a step that allowed its eventual use to modify human embryos.

Here is Zhang’s complete statement:

Although I appreciate the global threat posed by HIV, at this stage, the risks of editing embryos to knock out CCR5 seem to outweigh the potential benefits, not to mention that knocking out of CCR5 will likely render a person much more susceptible for West Nile Virus. Just as important, there are already common and highly-effective methods to prevent transmission of HIV from a parent to an unborn child.

Given the current state of the technology, I’m in favor of a moratorium on implantation of edited embryos, which seems to be the intention of the CCR5 trial, until we have come up with a thoughtful set of safety requirements first.

Not only do I see this as risky, but I am also deeply concerned about the lack of transparency surrounding this trial. All medical advances, gene editing or otherwise and particularly those that impact vulnerable populations, should be cautiously and thoughtfully tested, discussed openly with patients, physicians, scientists, and other community members, and implemented in an equitable way.

In 2015, the international research community said it would be irresponsible to proceed with any germline editing without “broad societal consensus about the appropriateness of the proposed application.” (This was the consensus statement from the 2015 International Summit on Human Gene Editing.)

It is my hope that the upcoming summit will serve as a forum for deeper conversations about the implications of this news and provide guidance on how we as a global society can best benefit from gene editing.