Artificial Intelligence / Voice Assistants

Your smartphone’s AI algorithms could tell if you are depressed

Smartphones that are used to track our faces and voices could also help lower the barrier to mental-health diagnosis and treatment.

Depression is a huge problem for millions of people, and it is often compounded by poor mental-health support and stigma. Early diagnosis can help, but many mental disorders are difficult to detect. The machine-learning algorithms that let smartphones identify faces or respond to our voices could help provide a universal and low-cost way of spotting the early signs and getting treatment where it’s needed.

In a study carried out by a team at Stanford University, scientists found that face and speech software can identify signals of depression with reasonable accuracy.

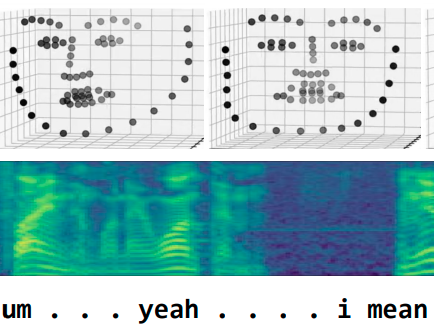

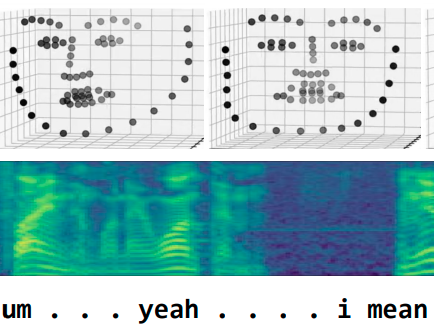

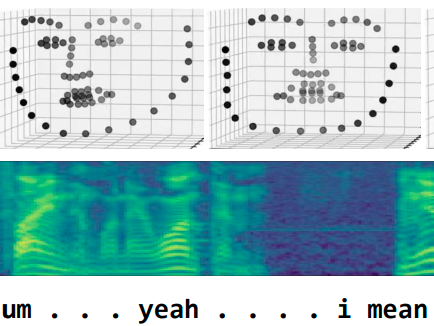

The researchers fed video footage of depressed and non-depressed people into a machine-learning model that was trained to learn from a combination of signals: facial expressions, voice tone, and spoken words. The data was collected from interviews in which a patient spoke to an avatar controlled by a physician.

In testing, it was able to detect whether someone was depressed more than 80% of the time. The research was led by Fei-Fei Li, a prominent AI expert who recently returned to Stanford from Google.

While the new work is at an early stage, the researchers suggest that it could someday provide an easier way for people to get diagnosed and helped.

“Compared to physical illnesses, mental disorders are more difficult to detect,” the researchers write in a paper that is being presented at the NeurIPS AI conference in Montreal this week. “The burden of mental health is exacerbated by barriers to care such as social stigma, financial cost, and a lack of accessible treatment options [...] This technology could be deployed to cell phones worldwide and facilitate low-cost universal access to mental health care.”

The researchers caution that the technology would not be a replacement for a clinician. They add that the data used did not include any protected health information, such as names, dates, or locations. They also note that further work would be needed to ensure that the technology is not biased toward a particular race or gender.

Justin Baker, a clinical psychiatrist at McLean Hospital, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who studies the use of technology for treating mental illness, is impressed by the way the system analyzes a patient’s face, voice, and language. “It is very cool because that’s what humans do very well,” he says. Baker says AI and smartphones could have a big impact if used carefully: “It’s both exciting and it has to be done really well with a lot of collaboration with clinical experts."

But David Sontag, an assistant professor at MIT who specializes in machine learning and health care, is cautious about the significance of the work. One catch, he says, is that the training data was gathered during an interview with a real clinician, albeit one behind an avatar, so it isn't clear if the diagnosis could be entirely automated. “The line of work is interesting,” he says,“but it’s not yet clear to me how it’ll be used clinically.”

Still, new approaches to detecting and treating mental-health conditions hold the promise of making treatment more accessible and perhaps more effective. Another research group at Stanford developed a chatbot to deliver simple cognitive behavioral therapy. The researchers say the approach has proved effective, and that many patients say they actually prefer speaking to a machine. This point is backed up by academic research.