Biotechnology

What if aging weren’t inevitable, but a curable disease?

If this controversial idea gains acceptance, it could radically change the way we treat getting old.

Each Cyclops had a single eye because, legend has it, the mythical giants traded the other one with the god Hades in return for the ability to see into the future. But Hades tricked them: the only vision the Cyclopes were shown was the day they would die. They carried this knowledge through their lives as a burden—the unending torture of being forewarned and yet having no ability to do anything about it.

Since ancient times, aging has been viewed as simply inevitable, unstoppable, nature’s way. “Natural causes” have long been blamed for deaths among the old, even if they died of a recognized pathological condition. The medical writer Galen argued back in the second century AD that aging is a natural process.

His view, the acceptance that one can die simply of old age, has dominated ever since. We think of aging as the accumulation of all the other conditions that get more common as we get older—cancer, dementia, physical frailty. All that tells us, though, is that we’re going to sicken and die; it doesn’t give us a way to change it. We don’t have much more control over our destiny than a Cyclops.

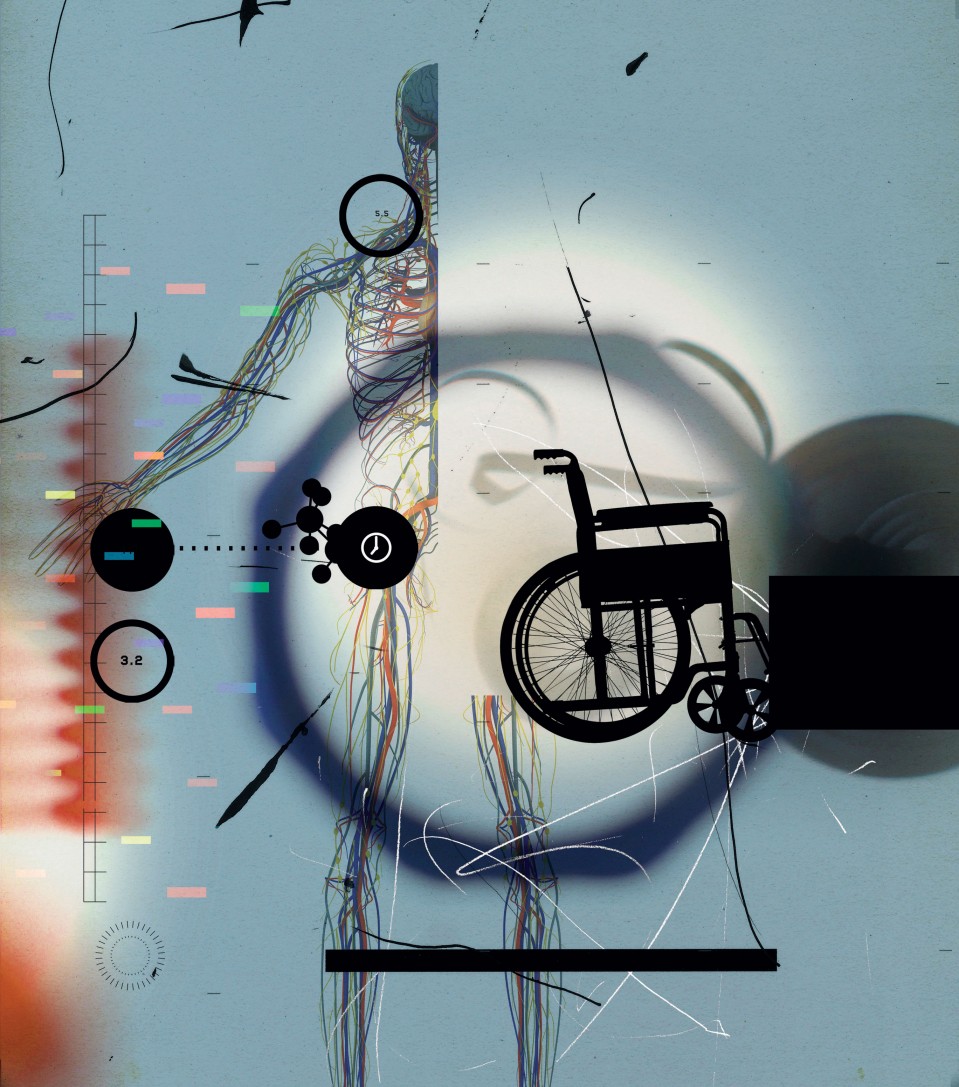

But a growing number of scientists are questioning our basic conception of aging. What if you could challenge your death—or even prevent it altogether? What if the panoply of diseases that strike us in old age are symptoms, not causes? What would change if we classified aging itself as the disease?

David Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, is one of those on the front line of this movement. Medicine, he argues, should view aging not as a natural consequence of growing older, but as a condition in and of itself. Old age, in his view, is simply a pathology—and, like all pathologies, can be successfully treated. If we labeled aging differently, it would give us a far greater ability to tackle it in itself, rather than just treating the diseases that accompany it.

“Many of the most serious diseases today are a function of aging. Thus, identifying the molecular mechanisms and treatments of aging should be an urgent priority,” he says. “Unless we address aging at its root cause, we’re not going to continue our linear, upward progress toward longer and longer life spans.”

It is a subtle shift, but one with big implications. How disease is classified and viewed by public health groups such as the World Health Organization (WHO) helps set priorities for governments and those who control funds. Regulators, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have strict rules that guide what conditions a drug can be licensed to act on, and so what conditions it can be prescribed and sold for. Today aging isn’t on the list. Sinclair says it should be, because otherwise the massive investment needed to find ways to fend it off won’t appear.

“Work to develop medicines that could potentially prevent and treat most major diseases is going far slower than it should be because we don’t recognize aging as a medical problem,” he says. “If aging were a treatable condition, then the money would flow into research, innovation, and drug development. Right now, what pharmaceutical or biotech company could go after aging as a condition if it doesn’t exist?” It should, he says, be the “biggest market of all.”

That’s precisely what worries some people, who think a gold rush into “anti-aging” drugs will set the wrong priorities for society.

It “turns a scientific discussion into a commercial or a political discussion,” says Eline Slagboom, a molecular epidemiologist who works on aging at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands. Viewing age as just a treatable disease shifts the emphasis away from healthy living, she says. Instead, she argues, policymakers and medical professionals need to do more to prevent chronic diseases of old age by encouraging people to adopt healthier lifestyles while they are still young or middle-aged. Otherwise, the message is “that we can’t do anything with anybody [as they age] until they reach a threshold at the point where they get sick or age rapidly, and then we give them medication.”

Another common objection to the aging-as-a-disease hypothesis is that labeling old people as diseased will add to the stigma they already face. “Ageism is the biggest ism we have today in the world,” says Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. “The aging community is attacked. People are fired from work because they are old. Old people cannot get jobs. To go to those people with so many problems and now tell them, ‘You’re sick, you have a disease’? This is a no-win situation for the people we are trying to help.”

Not everyone agrees it has to be a stigma. “I am clearly in favor of calling aging a disease,” says Sven Bulterijs, cofounder of the Healthy Life Extension Society, a nonprofit organization in Brussels that considers aging a “universal human tragedy” with a root cause that can be found and tackled to make people live longer. “We don’t say for cancer patients that it’s insulting to call it a disease.”

Notwithstanding Sinclair’s comment about “linear, upward progress,” just how long humans could live remains bitterly contested. The underlying, fundamental question: Do we have to die at all? If we found a way to both treat and beat aging as a disease, would we live for centuries—millennia, even? Or is there an ultimate limit?

Nature suggests that endless life might not be inconceivable. Most famously, perhaps, the bristlecone pine trees of North America are considered biologically immortal. They can die—chopped down by an ax or zapped by a lightning bolt—but left undisturbed, they typically won’t simply fall over because they get old. Some are reckoned to be 5,000 years young; age, quite literally, does not wither them. Their secret remains a mystery. Other species appear to show signs of biological immortality as well, including some sea creatures.

Such observations have led many to contend that life span can be dramatically extended with the right interventions. But in 2016, a high-profile study published in Nature argued that human life has a hard limit of about 115 years. This estimate is based on global demographic data showing that improvements in survival with age tend to decline after 100, and that the record for human longevity hasn’t increased since the 1990s. Other researchers have disputed the way the analysis was done.

Barzilai says efforts to tackle aging are needed regardless. “We can argue about if it’s 115 or 122 or 110 years,” he says. “Now we die before the age of 80, so we have 35 years that we are not realizing now. So let’s start realizing those years before we’re talking about immortality or somewhere in between.”

Whether or not they believe in either the disease hypothesis or maximum life spans, most experts agree that something has to change in the way we deal with aging. “If we don’t do something about the dramatic increase in older people, and find ways to keep them healthy and functional, then we have a major quality-of-life issue and a major economic issue on our hands,” says Brian Kennedy, the director of Singapore’s Centre for Healthy Ageing and a professor of biochemistry and physiology at the National University of Singapore. “We have to go out and find ways to slow aging down.”

The aging population is the “climate change of health care,” Kennedy says. It’s an appropriate metaphor. As with global warming, many of the solutions rest on changing people’s behavior—for example, modifications to diet and lifestyle. But, also as with global warming, much of the world seems instead to be pinning its hopes on a technological fix. Maybe the future will involve not just geoengineering but also gero-engineering.

One thing that may underlie the growing calls to reclassify aging as a disease is a shift in social attitudes. Morten Hillgaard Bülow, a historian of medicine at the University of Copenhagen, says things started to change in the 1980s, when the idea of “successful aging” took hold. Starting with studies organized and funded by the MacArthur Foundation in the United States, aging experts began to argue against Galen’s centuries-old stoic acceptance of decline, and said scientists should find ways to intervene. The US government, aware of the health implications of an aging population, agreed. At the same time, advances in molecular biology led to new attention from researchers. All that sent money flowing into research on what aging is and what causes it.

In the Netherlands, Slagboom is trying to develop tests to identify who is aging at a normal rate, and who has a body older than its years. She sees anti-aging medicine as a last resort but says understanding someone’s biological age can help determine how to treat age-related conditions. Take, for instance, a 70-year-old man with mildly elevated blood pressure. If he has the circulatory system of an 80-year-old, then the elevated pressure could help blood reach his brain. But if he has the body of a 60-year-old, he probably needs treatment.

Biomarkers that can identify biological age are a popular tool in aging research, says Vadim Gladyshev of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He characterizes aging as the accumulation of deleterious changes across the body, ranging from shifts in the populations of bacteria that live in our gut to differences in the degree of chemical scarring on our DNA, known as methylation. These are biological measures that can be tracked, so they can also be used to monitor the effectiveness of anti-aging drugs. “Once we can measure and quantify the progression through aging, then that gives us a tool to assess longevity interventions,” he says.

Two decades on, the results of that research are becoming apparent. Studies in mice, worms, and other model organisms have revealed what’s going on in aging cells and come up with various ways to extend life—sometimes to extraordinary lengths.

Most researchers have more modest goals, with a focus on improving what they call “health span”—how long people remain independent and functional. And they say they’re making progress, with a handful of possible pills in the pipeline.

One promising treatment is metformin. It’s a common diabetes drug that has been around for many years, but animal studies suggest it could also protect against frailty, Alzheimer’s, and cancer. Giving it to healthy people might help delay aging, but without official guidance doctors are reluctant to prescribe it that way.

One group of researchers, including Einstein College’s Barzilai, is trying to change that. Barzilai is leading a human trial called TAME (Targeting Aging with Metformin) that plans to give the drug to people aged 65 to 80 to see if it delays problems such as cancer, dementia, stroke, and heart attacks. Although the trial has struggled to raise funding—partly because metformin is a generic drug, which reduces potential profits for drug companies—Barzilai says he and his colleagues are now ready to recruit patients and start later this year.

Metformin is one of a broader class of drugs called mTOR inhibitors. These interfere with a cell protein involved in division and growth. By turning the protein’s activity down, scientists think they can mimic the known benefits of calorie restriction diets. These diets can make animals live longer; it’s thought that the body may respond to the lack of food by taking protective measures. Preliminary human tests suggest the drugs can boost older people’s immune systems and stop them from catching infectious bugs.

Other researchers are looking at why organs start to pack up as their cells age, a process called senescence. Among the leading candidates for targeting and removing these decrepit cells from otherwise healthy tissues is a class of compounds called senolytics. These encourage the aged cells to selectively self-destruct so the immune system can clean them out. Studies have found that older mice on these drugs age more slowly. In humans, senescent cells are blamed for diseases ranging from atherosclerosis and cataracts to Parkinson’s and osteoarthritis. Small human trials of senolytics are under way, although they aren’t officially aimed at aging itself, but on the recognized illnesses of osteoarthritis and a lung disease called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Research on these drugs has highlighted a key question about aging: Is there a common mechanism by which different tissues change and decline? If so, could we find drugs to target that mechanism instead of playing what Harvard’s David Sinclair calls “whack-a-mole” medicine, treating individual diseases as they emerge? He believes there is, and that he has found a stunning new way to rewind the aging clock.

In unpublished work described in his coming book Lifespan, he says the key to his lab’s work in this area is epigenetics. This fast-moving field focuses on how changes to the way genes are expressed, rather than mutations to the DNA itself, can produce physiological changes such as disease. Some of the body’s own epigenetic mechanisms work to protect its cells, repairing damage to DNA, for instance; but they become less effective with age. Sinclair claims to have used gene therapy to effectively recharge these mechanisms in mice, and he says he can “make damaged optic-nerve cells young again” to restore sight to elderly blind animals.

We have been here before. Many scientists thought they had found a fountain of youth in animal studies, only to have the results dry up when they turned their attention to people. But Sinclair is convinced he is on to something. He says he’ll soon publish the results in a scientific journal for other researchers to examine.

Because aging isn’t officially a disease, most research on these drugs exists in a gray area: they don’t—or can’t—officially tackle aging. For example, Barzilai’s metformin project, the closest the world has right now to a clinical trial for a drug that targets aging, aims to prevent diseases associated with aging rather than aging itself, as do the trials on senolytics. “And one of the side effects is you might live longer,” he says.

Barzilai won’t go so far as to say aging should be reclassified as a disease, but he does say that if it were, discoveries might happen faster. Studies like TAME have to give people a drug, then wait years and years to see if it prevents some of them from developing an age-related disease. And because that effect is likely to be relatively small, it takes huge numbers of people to prove anything. If aging were instead considered a disease, trials could focus on something quicker and cheaper to prove—such as whether the drug slows the progression from one stage of aging to another.

The Healthy Life Extension Society is part of a group that last year asked the WHO to include aging in the latest revision of its official International Classification of Diseases, ICD-11. The WHO declined, but it did list “aging-related” as an extension code that can be applied to a disease, to indicate that age increases the risk of getting it.

To try to put research into treatments that target aging on a more scientific footing, a different group of scientists is preparing to revisit the issue with the WHO. Coordinated by Stuart Calimport, a former advisor to the SENS Research Foundation in California, which promotes research on aging, the detailed proposal—a copy of which has been seen by MIT Technology Review—suggests that each tissue, organ, and gland in the body should be scored—say, from 1 to 5—on how susceptible it is to aging. This so-called staging process has already helped develop cancer treatments. In theory, it could allow drugs to be licensed if they are shown to stop or delay the aging of cells in a region of the body.

Reclassifying aging as a disease could have another big benefit. David Gems, a professor of the biology of aging at University College London, says it would provide a way to crack down on quack anti-aging products. “That would essentially protect older people from the swirling swamp of exploitation of the anti-aging business. They’re able to make all sorts of claims because it’s not legally a disease,” Gems says.

In February, for instance, the FDA was forced to warn consumers that injections of blood from younger people—a procedure that costs thousands of dollars and has become increasingly popular around the world—had no proven clinical benefit. But it couldn’t ban the injections outright. By calling them an anti-aging treatment, companies escape the strict oversight applied to drugs that claim to target a specific disease.

Like the Cyclops, Singapore has been given a glimpse of what is to come—and officials there do not like what they see. The island nation is on the front line of the gray surge. By 2030, if current trends continue, there will be just two people working there for every retired person (by comparison, the US will have three people in the workforce for every resident over 65). So the country is trying to change the script, to find a happier and healthier ending.

With the help of volunteer subjects, Kennedy of Singapore’s Centre for Healthy Ageing is preparing the first wide-ranging human tests of aging treatments. Kennedy says he’s aiming to trial 10 to 15 possible interventions—he won’t say which, for now—in small groups of people in their 50s: “I’m thinking maybe three or four drugs and a few supplements, and then compare those to lifestyle modifications.”

The Singapore government has prioritized strategies to deal with the aging population and Kennedy wants to create a “test bed” for such human experiments. “We have made great progress in animals,” he adds, “but we need to begin to do these tests in people.”

David Adam is a freelance writer and editor, and the author of The Man Who Couldn’t Stop.