Space

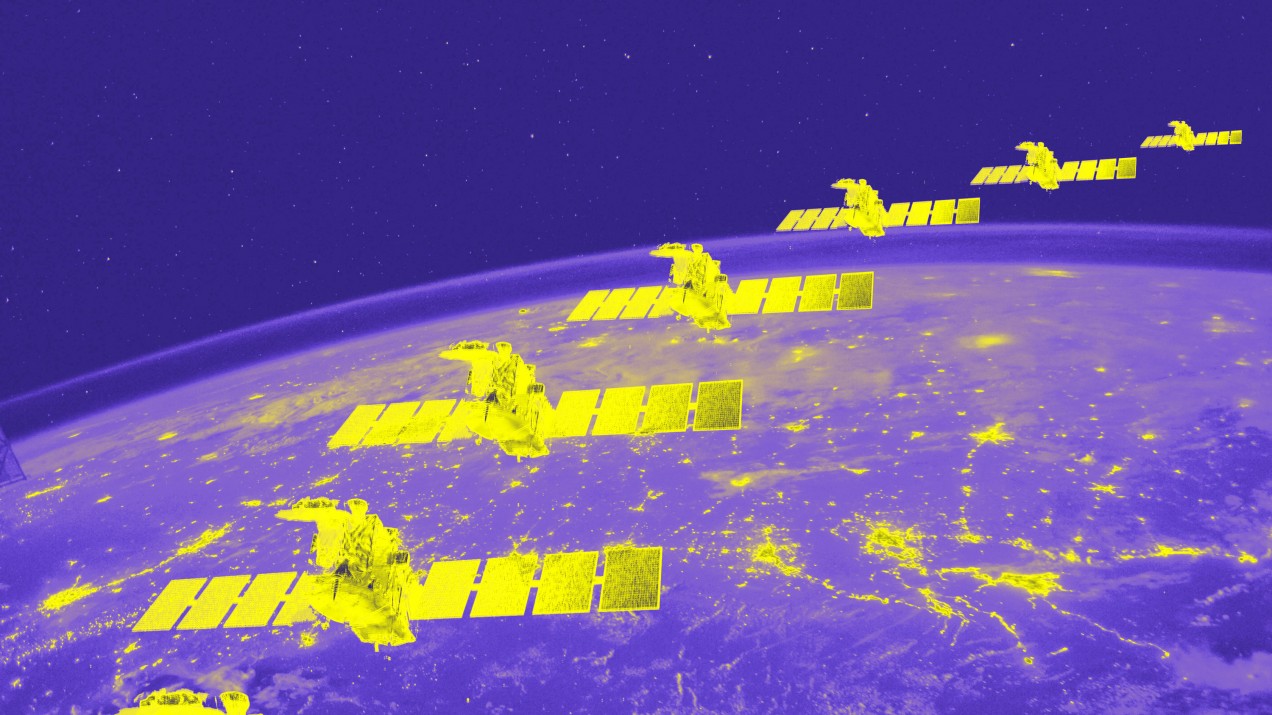

Do satellite mega-constellations really have to be so big?

Maybe we need a cap on how many satellites internet firms are allowed to send into orbit.

“There are no rules in space,” Greg Wyler said at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference last Thursday. His company, OneWeb, wants to launch 2,000 satellites into space—practically doubling the number of satellites currently orbiting Earth—in order to deliver internet connectivity to unconnected places. As long as he has permission to access the radio frequency spectrum he’s requested, there’s no one to really stop him. Nor is there anyone to stop SpaceX from launching a whopping 12,000 satellites over the next several years in order to operate its Starlink internet service.

The rise of these satellite mega-constellations is creating concern that we’re heading toward the debacle known as the Kessler syndrome (named after the NASA scientist who first proposed the possible scenario), where Earth’s orbit becomes polluted by dangerous debris as a result of numerous satellite collisions. The debris would threaten every piece of equipment that’s zipping around the planet and render space unsafe for any new spacecraft. Recent near-misses have only exacerbated those fears, and the lack of current rules means there’s nothing stopping any companies from arbitrarily launching more objects into the sky. Which raises a question—do these companies really need to send tens of thousands of these things into space?

You have to keep in mind your target market, says Dan Hays, the principal for global tech, media, and telecom at PricewaterhouseCoopers. He says that while most of the satellites are practically identical, there are a number of reasons why some firms—such as SpaceX—would elect to launch way more than others. These companies “have different business strategies and different customer segments that they’re targeting,” he says, “and those might require different capabilities.”

You can’t repair satellites the way you would a cell tower, so many of your satellites might simply be spares to replace any that fail, for example. And if you’re setting up your constellation in lower altitudes, you’ll need more satellites to cover more areas. (Starlink’s satellites will go into three orbital shells at 210, 340, and 710 miles, respectively. OneWeb’s will operate at an altitude of around 750 miles.)

Both OneWeb and SpaceX are vying for global coverage, but Wyler is going after emerging markets, not developed ones. And to that end, he’s prioritized efficiency. “You want to be more efficient with less because you’re managing less; you’re controlling less; you’re dealing with less conjunctions; and you’re taking up less space,” he says. He’s not looking to compete with terrestrial broadband services.

The scope of Starlink suggests that this is SpaceX’s goal—in spite of the risks. Until now, the biggest problem with satellite internet has been latency. SpaceX intends each Starlink satellite to link up with four others, which the company claims will help beam data back to Earth even faster than the speeds achieved by fiber optics.

But what happens if these technologies become obsolete? Since all the mega-constellations are in low Earth orbit, the prudent thing would be to ensure that defunct satellites have enough fuel to de-orbit, but that’s a lot of objects to coordinate. And the difference between managing a thousand and ten thousand satellites is huge.

In view of all this, Wyler suggests that the only reason to launch more satellites than necessary is for show. “The number of satellites makes the company,” he says. “More is better, from a public and fund-raising standpoint.”

Hays doesn’t disagree. “We certainly seem to be in an era of modern-day satellite wars—an arms race for who can announce the largest constellation,” he says. But the number of satellites will not automatically guarantee success; nor will it automatically mean disaster is looming. “The big issue,” he says, “is can anybody make money on this?” The answer to that question is going to tell us whether mega-constellations are just a short-lived trend—or a new way of doing space for the next century.