A Camera Made from Many Produces Gigapixel Images

A research project shows how a revolutionary type of camera could be commercialized.

Imagine trying to spot an individual pixel in an image displayed across 1,000 high-definition TV screens. That’s the kind of resolution a new kind of “compact” gigapixel camera is capable of producing.

Developed by David Brady and colleagues at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, the new camera is not the first to generate images with more than a billion pixels (or gigapixel resolution). But it is the first with the potential to be scaled down to portable dimensions. Gigapixel cameras could not only transform digital photography, says Brady, but they could revolutionize image surveillance and video broadcasting.

Until now, gigapixel images have been generated either by creating very large film negatives and then scanning them at extremely high resolutions or by taking lots of separate digital images and then stitching them together into a mosaic on a computer. While both approaches can produce stunningly detailed images, the use of film is slow, and setting up hundreds of separate digital cameras to capture an image simultaneously is normally less than practical.

It is not possible to simply scale up a normal digital camera by increasing the number of light sensors to a billion, because this would require a lens so large that imperfections on its surface would cause distortion.

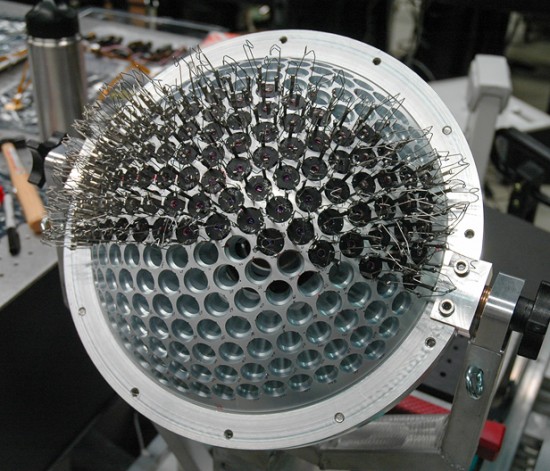

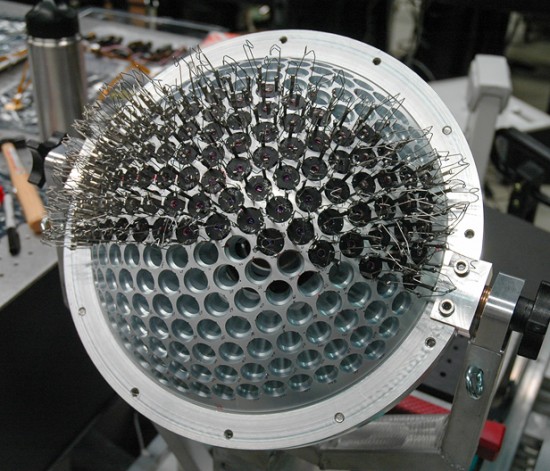

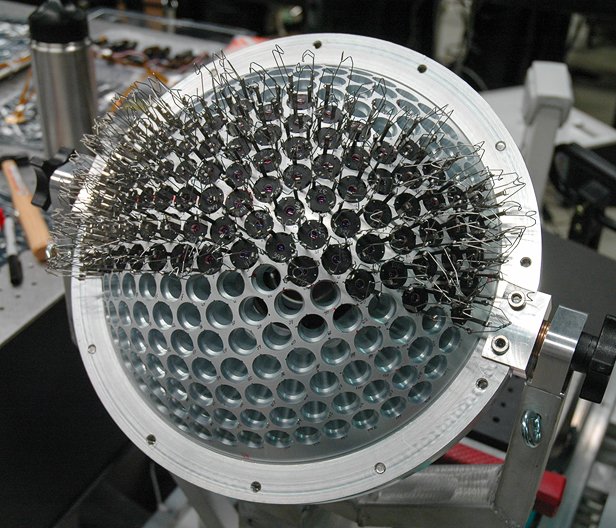

Brady’s solution, a camera called AWARE, has 98 micro-cameras similar to those found in smart phones, each with 10-megapixel resolution. By positioning these high quality micro-cameras behind a shared lens, it becomes possible to process different portions of the image separately and to correct for known distortions. “We realized we could turn this into a parallel-processing problem,” Brady says.

The corrections are made possible by eight graphical processing units working in parallel. Breaking the problem up this way allows more complex techniques to be used to correct for optical aberrations, says Illah Nourbakhsh a lead researcher of a similar project, called Gigapan, at Carnegie Mellon University.

Eventually, as computer processing power improves, the hardware needed for such a camera should shrink. Portable gigapixel resolution could be useful in a number of ways. For example, additional pixels already help with image stabilization. “Also, if you increase the resolution, you increase the chances of automated recognition and artificial intelligence systems being able to accurately recognize things in the world,” Nourbakhsh says.

The project is described in this week’s issue of the journal Nature. In one gigapixel image of Pungo Lake in the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, Brady’s group shows that individual swans in the extreme distance can be resolved. The picture was taken using a prototype camera capable of capturing and processing an entire image in just 18 seconds.

As graphical processors improve, so too will the speed of the camera, says Bradley. And although the prototype currently stands 75 centimeters tall–about the size of a television studio camera—the device’s size is dictated in large part by the equipment needed to cool the circuit boards.

“In the near term, we think this concept of a micro-camera imaging system is the future of cameras,” says Brady. By the end of next year, his group hopes to be able to produce and sell 100 units a year, each costing around $100,000. This is comparable to the cost of a broadcast TV camera, he says.

Gigapixel cameras could eventually allow events to be covered in new ways. “Rather than showing a camera angle that the producer lets you see, the viewer will be able to see anything in the scene that they want,” Brady says.