Building a better gait

Affordable prosthetic foot mimics natural walking.

Advanced prosthetics offer amputees a wide range of bionic options. But they can cost tens of thousands of dollars, making them unattainable for many.

Now MIT engineers have developed a simple, low-cost, customizable artificial foot that, though it has no electronics or moving parts, affords a gait similar to that of an able-bodied person. The researchers estimate that the prosthetic, if manufactured on a wide scale, could cost an order of magnitude less than existing products.

In 2012, soon after Amos Winter, SM ’05, PhD ’11, joined the mechanical engineering faculty, he was approached by the artificial-limb manufacturer Jaipur Foot, which donates thousands of its prosthetic feet to users in India and elsewhere each year. “They’ve been making this foot for over 40 years, and it’s rugged, so farmers can use it barefoot outdoors, and it’s relatively life-like,” says Winter. “But it’s quite heavy, and the internal structure is made all by hand, which creates a big variation in product quality.” Jaipur Foot asked Winter to design a better, lighter foot that could be mass-produced at low cost.

In rethinking the typical foot design, Winter’s team, led by Kathryn Olesnavage ’12, SM ’14, PhD ’18, realized that amputees who have lost a limb below the knee can’t feel what a prosthetic foot does. “To a user, the foot is just kind of like a black box,” says Winter. “It’s not connected to their nervous system, and they’re not interacting with the foot intimately.”

So instead of trying to replicate the motions of an able-bodied foot, they focused on the motions of the lower leg.

After developing a mathematical model describing the prosthetic’s stiffness, possible motion, and shape, they plugged in data on ground reaction forces collected from able-bodied walkers, which they could sum up to predict how a user’s lower leg would move through a single step. Then they tuned the stiffness and geometry of the simulated foot to produce a lower-leg trajectory similar to the able-bodied motion.

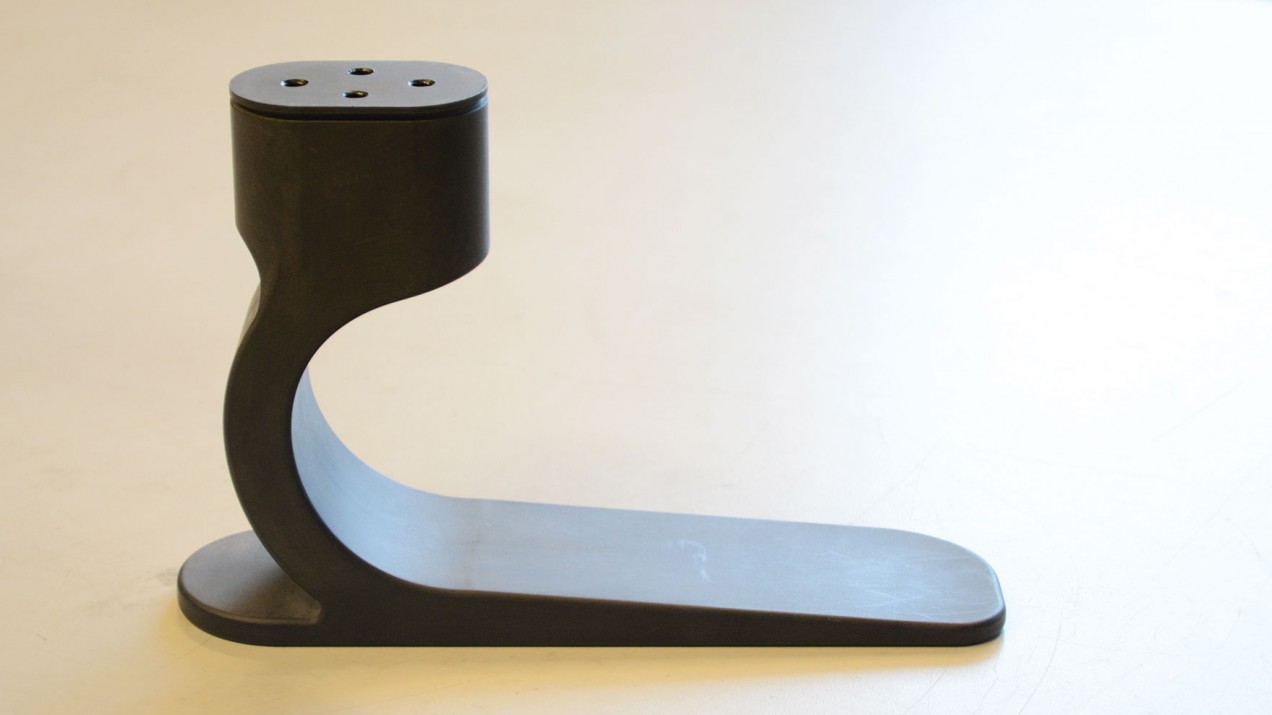

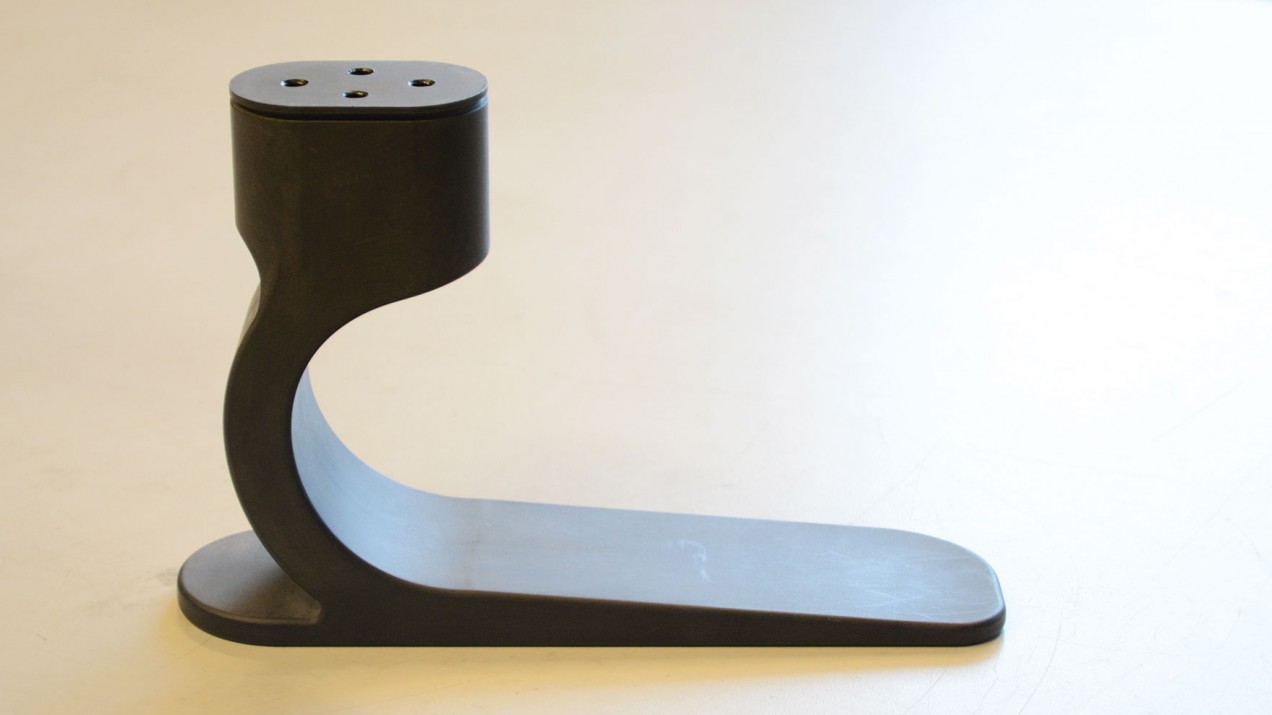

To pinpoint an ideal foot shape, the group simulated a variety of feet, eliminating the shapes that didn’t produce something close to an able-bodied gait in the model. Then they mixed and matched features of the remaining shapes to arrive at one that produced the most natural lower-leg trajectory. The result looks similar to the side view of a toboggan.

Olesnavage and Winter figured that if they varied the stiffness and shape according to a person’s body weight and size, the prosthetic would also generate leg motions similar to able-bodied walking. To test this idea, they fashioned several feet for volunteers in India using machined nylon, a material chosen for its energy storage capability.

“What’s cool is this behaves nothing like an able-bodied foot—there’s no ankle or metatarsal joint,” Winter says. “It’s just one big structure, and all we care about is how the lower leg is moving through space. Most of the testing was done indoors, but one guy ran outside, he liked it so much. It puts a spring in your step.”

Italian hiking boot manufacturer Vibram is designing a lifelike covering for the prosthesis that will also give it traction on muddy or slippery surfaces. The researchers plan to test the prostheses and coverings on volunteers in India next summer.

“This model is potentially game-changing for the industry,” says Winter, “because we can fully quantify the foot and tune it for individuals, and use cheaper materials.”