A book for the ages

A new analysis reveals the chemistry of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The ancient Hebrew Dead Sea Scrolls are among the most well-preserved ancient written materials ever found. Now a study by researchers at MIT and elsewhere reveals the unique technology used to make their parchment, and it may help preserve them.

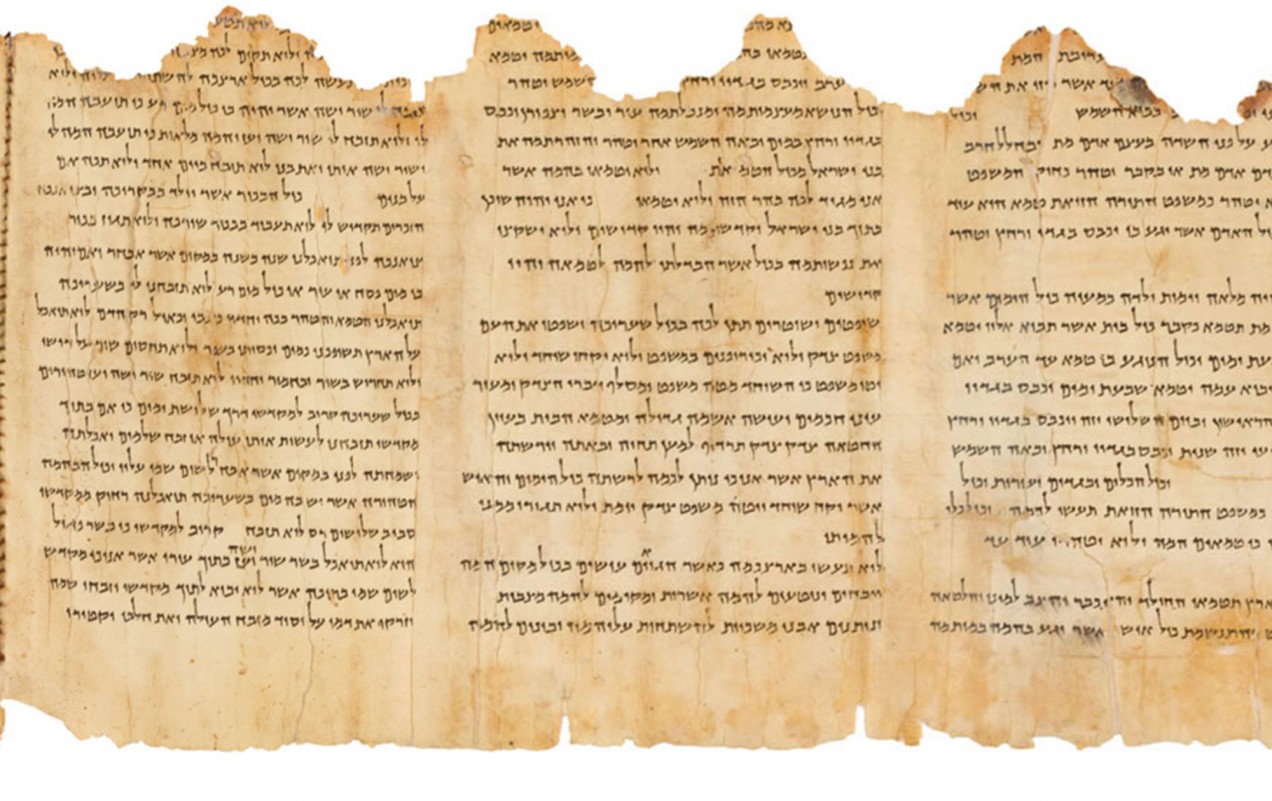

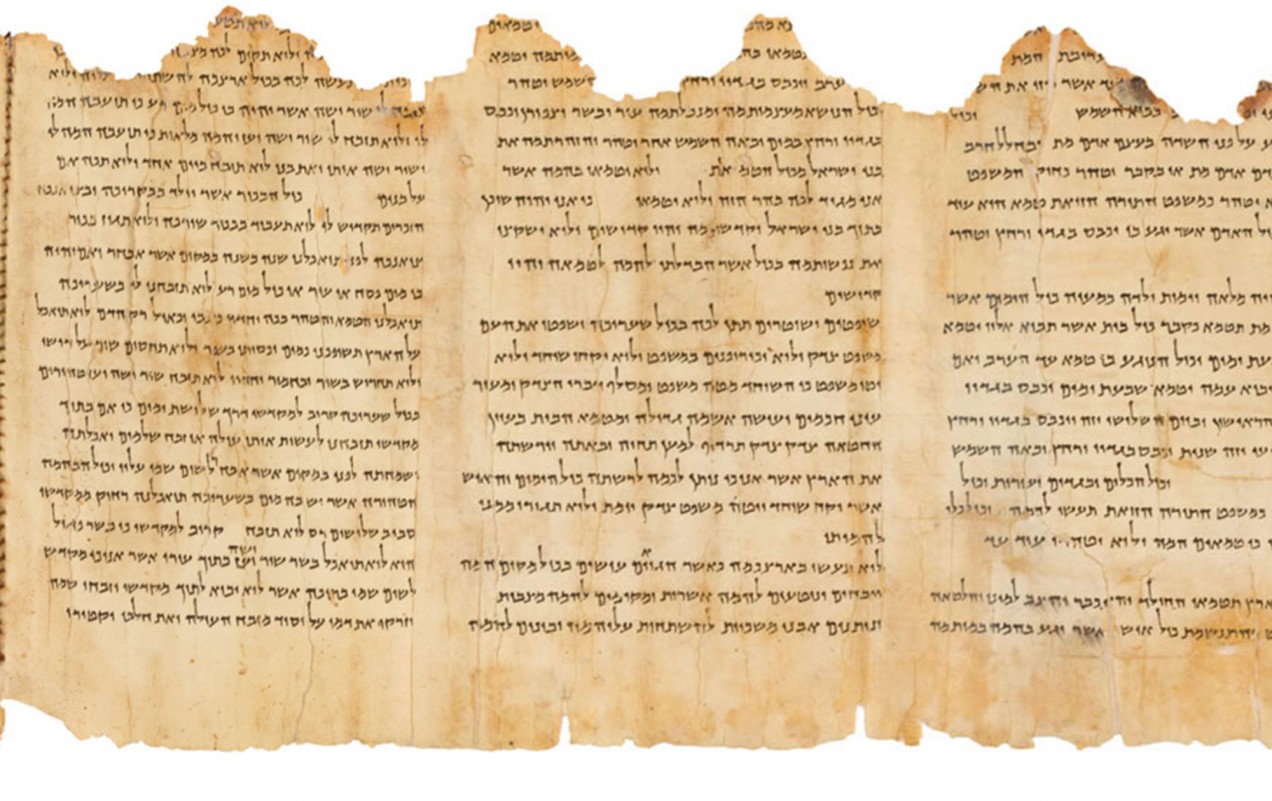

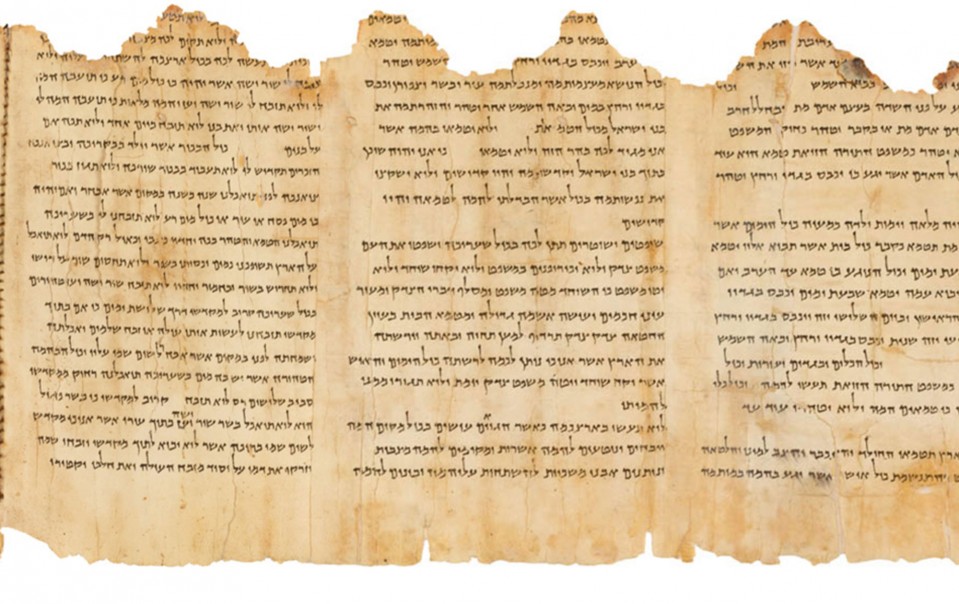

The study focused on the Temple Scroll (below), one of the largest and best-preserved of the scrolls found in jars in caves near the Dead Sea, where the Essenes hid them from the Romans 2,000 years ago.

Assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering Admir Masic and colleagues used specialized tools to map the chemical composition of a one-inch fragment from the Temple Scroll at submicron scale. They found that the parchment was coated with an unusual mixture of brine evaporates—including sulfur, sodium, and calcium—that did not match the composition of the Dead Sea. The fragment “allowed us to look deeply into its original composition, revealing the presence of some elements at completely unexpectedly high concentrations,” Masic says.

The coating helped give the parchment its unusually bright white surface and shows that the Temple Scroll was produced using techniques atypical of the region. Understanding the details of this ancient technology could provide insights into the culture and society of that time and place, revealing trade routes used to obtain the material. It could also help preserve the manuscripts, which appear to have been damaged by efforts to unroll them immediately after their discovery. The mineral coatings might absorb moisture from the air and degrade the underlying material if they do. The research underscores the need to store the parchments in a controlled-humidity environment at all times.