The Shrinkage Solution

Wherein a pair of MIT civil engineers proposed a novel way to lessen our environmental impact.

In 1966, a Nobel Prize-winning biologist named Joshua Lederberg suggested, in an essay in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, that because human evolution could now be directed by scientific means, we ought to seriously consider what kinds of changes we might like to see. A year later, in a provocative—and bizarre—essay for the July 1967 issue of Technology Review, a pair of MIT civil-engineering professors named Robert Hansen and Myle Holley considered one such change: making people smaller.

We wish here to comment on one kind of human change—a change of physical size—which apparently would be far less difficult to achieve than the modifications we infer to be potentially feasible through genetic alchemy. Indeed, it is our understanding that controlled, substantial modification of size may require only the judicious application of findings in the area of endocrinology.

The authors never got into the specifics of how humans might be made smaller, or how much smaller they should be. They acknowledged that the idea would probably generate “widespread antagonism,” but they argued that given our emerging capacity for genetic engineering, it would be reckless to ignore the possibilities altogether: “Can we afford not to consider, in all its aspects, the question of human size?”

If, as the authors believe, the question of human size merits thought, it appears more reasonable to consider a decrease rather than an increase in size. First, an increase in size would clearly aggravate the problems we already associate with our excessive rate of population growth. Second, the advantages of large size and physical strength (in the performance of useful labor, the resolution of individual and group conflicts, etc.) have been almost entirely eliminated by technology.

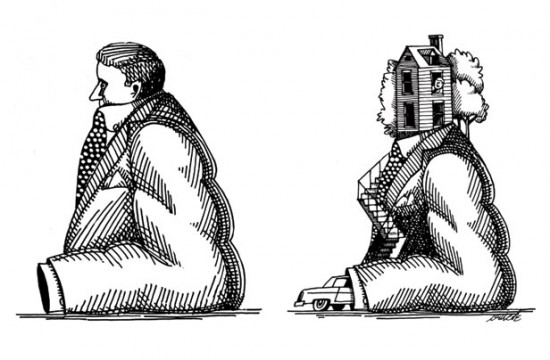

Smaller people, they wrote, would need less food and tinier houses. They’d create less waste. And the smaller you are, the bigger the world seems. “A reduction in man’s size might be compared to an increase in the size of the earth,” the authors noted.

Consider, as but one example, the relation of man’s size to the facilities provided for his transportation. Smaller man could mean smaller vehicles, either smaller highway rights of way or greater capacity for existing highways, easier provision for off-street parking ... Similar benefits of smaller human size become apparent in buildings.

In a section called “What Price Man’s Shrinkage?” they addressed the “problems of transition.” For instance: How would people react emotionally to such a proposal? Would they be less able to endure cold weather? And at what rate should the shrinkage occur? Five percent per decade? Twenty-five percent?

Allowing for an inevitable transition period, will smaller man really be comfortable in lesser space (or volume) than his larger predecessors have come to expect? … If a change in size appears desirable, what incentives, if any, will lead to its achievement through free, individual choice?

Strange as the argument sounds, it did resonate as late as 1995, when an essay in The Futurist briefly cited Hansen and Holley’s work in TR before pointing out that pygmies are physically fine at four and a half feet tall. Hansen and Holley emphasized that they weren’t necessarily advocating making people smaller—they were simply (as Lederberg advised) giving the idea the careful thought they believed it deserved.

Needless to say effective consideration of this question will require not only effort within the scientific and humanistic communities, but frank and sympathetic interactions between the two. The end product of such inquiry and debate is not predictable. Possible conclusions range from feasibility, desirability, and moral acceptability to impossibility for technical, social, or other reasons. But need we prejudge the issue? Or should we seriously study the question?

Timothy Maher is TR ’s assistant managing editor.