Tech Policy / Tech and Health

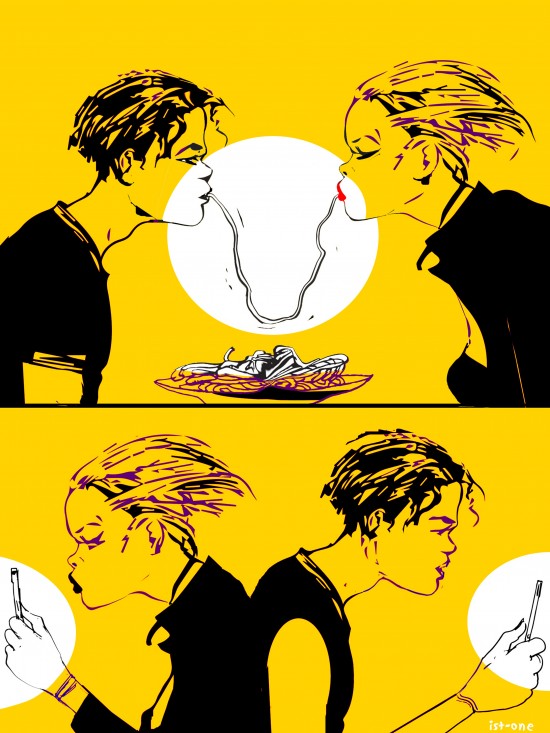

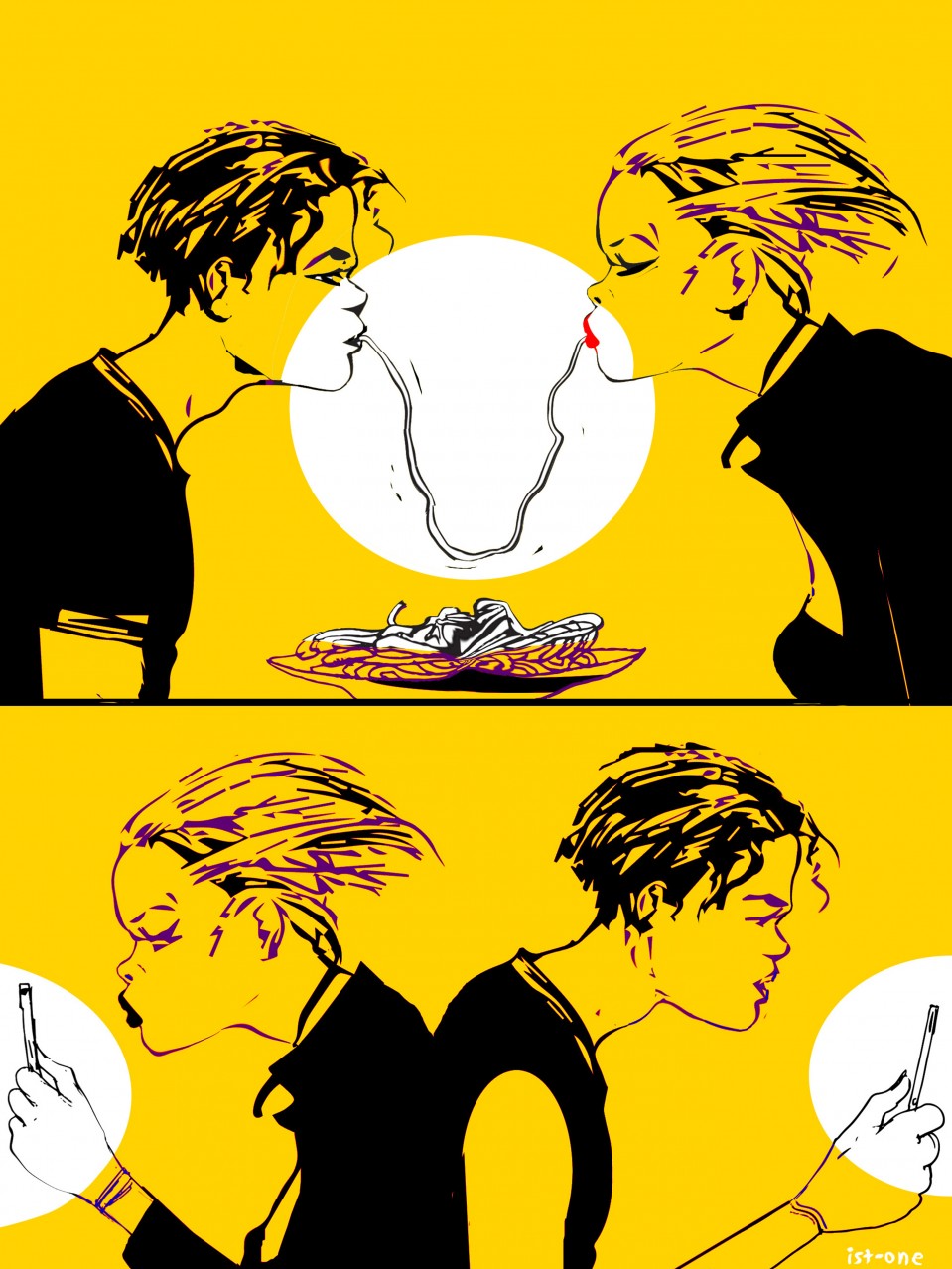

Romancing the Phone

Love and sex in the age of social media and mobile communication.

Boy meets girl; they grow up and fall in love. But technology interferes and threatens to destroy their blissful coupledom. The destructive potential of communication technologies is at the heart of Stephanie Jones’s self-published romance novel Dreams and Misunderstandings. Two childhood sweethearts, Rick and Jessie, use text messages, phone calls, and e-mail to manage the distance between them as Jessie attends college on the East Coast of the United States and Rick moves between Great Britain and the American West. Shortly before a summer reunion, their technological ties fail when Jessie is hospitalized after a traumatic attack. During her recovery, she loses access to her mobile phone, computer, and e-mail account. As a result, the lovers do not reunite and spend years apart, both thinking they have been deserted.

Jones blames digital innovations for the misunderstandings that prevent Rick and Jessie’s reunion. It’s no surprise this theme runs through a romance novel: it reflects a wider cultural fear that these technologies impede rather than strengthen human connection. One of the Internet’s earliest boosters, MIT professor Sherry Turkle, makes similar claims in her most recent book, Alone Together: Why We Expect More of Technology and Less from Each Other. She argues that despite their potential, communication technologies are threatening human relationships, especially intimate ones, because they offer “substitutes for connecting with each other face-to-face.”

If the technology is not fraying or undermining existing relationships, stories abound of how it is creating false or destructive ones among young people who send each other sexually explicit cell-phone photos or “catfish,” luring the credulous into online relationships with fabricated personalities. In her recent book about hookup culture, The End of Sex, Donna Freitas indicts mobile technologies for the ease with which they allow the hookup to happen.

It is true that communication technologies have been reshaping love, romance, and sex throughout the 2000s. The Internet, sociologists Michael Rosenfeld and Reuben Thomas have found, is now the third most common way to find a partner, after meeting through friends or in bars, restaurants, and other public places. Twenty-two percent of heterosexual couples now meet online. In many ways, the Internet has replaced families, churches, schools, neighborhoods, civic groups, and workplaces as a venue for finding romance. It has become especially important for those who have a “thin market” of potential romantic partners—middle-aged straight people, gays and lesbians of all ages, the elderly, and the geographically isolated. But even for those who are not isolated from current or potential partners, cell phones, social-network sites, and similar forms of communication now often play a central role in the formation, maintenance, and dissolution of intimate relationships.

While these developments are significant, fears about what they mean do not accurately reflect the complexity of how the technology is really used. This is not surprising: concerns about technology as a threat to the social order, particularly in matters of sexuality and intimacy, go back much further than Internet dating and cell phones. From the boxcar (critics worried that it could transport those of loose moral character from town to town) to the automobile (which gave young people a private space for sexual activity) to reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization, technological innovations that affect intimate life have always prompted angst. Often, these fears have resulted in what sociologists call a “moral panic”—an episode of exaggerated public anxiety over a perceived threat to social order.

Moral panic is an appropriate description for the fears expressed by Jones, Turkle, and Freitas about the role of technology in romantic relationships. Rather than driving people apart, technology-mediated communication is likely to have a “hyperpersonal effect,” communications professor Joseph Walther has found. That is, it allows people to be more intimate with one another—sometimes more intimate than would be sustainable face to face. “John,” a college freshman in Chicago whom I interviewed for research that I published in a 2009 book, Hanging Out, Messing Around and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media, highlights this paradox. He asks, “What happens after you’ve had a great online flirtatious chat … and then the conversation sucks in person?”

In the initial getting-to-know-you phase of a relationship, the asynchronous nature of written communication—texts, e-mails, and messages or comments on dating or social-network sites, as opposed to phone calls or video chatting—allows people to interact more continuously and to save face in potentially vulnerable situations. As people flirt and get to know each other this way, they can plan, edit, and reflect upon flirtatious messages before sending them. As John says of this type of communication, “I can think about things more. You can deliberate and answer however you want.”

As couples move into committed relationships, they use these communication technologies to maintain a digital togetherness regardless of their physical distance. With technologies like mobile phones and social-network sites, couples need never be truly apart. Often, this strengthens intimate relationships: in a study on couples’ use of technology in romantic relationships, Borae Jin and Jorge Peña found that couples who are in greater cell-phone contact exhibit less uncertainty about their relationships and higher levels of commitment. This type of communication becomes a form of “relationship work” in which couples trade digital objects of affection such as text messages or comments on online photos. As “Champ,” a 19-year-old in New York, told one of my collaborators on Hanging Out, Messing Around and Geeking Out about his relationship with his girlfriend, “You send a little text message—‘Oh I’m thinking of you,’ or something like that—while she’s working … Three times out of the day, you probably send little comments.”

To be sure, some of today’s fears are based on the perfectly accurate observation that communication technologies don’t always lend themselves to constructive relationship work. The public nature of Facebook posts, for example, appears to promote jealousy and decrease intimacy. When the anthropologist Ilana Gershon interviewed college students about their romantic lives, several told her that Facebook threatens their relationships. As one of her interviewees, “Cole,” said: “There is so much drama. It’s adding another stress.”

But overall, the research by Gershon and others indicates that people often have a shared understanding of how and when technology should be used in romantic relationships. In fact, in no small part because people primarily use social media to express connection, they do not like using it to end relationships. Only 25 percent of social-media users claim that they would use technology to discuss serious issues with their partners, and a very small number reported that they would terminate their relationship that way. When Gershon asked students at her university to describe a “bad” breakup, they immediately discussed any breakup that was initiated via social media. In Hanging Out, Messing Around and Geeking Out, “Grady,” a 16-year-old high-school student, said that breaking up by text or social network was especially “disrespectful,” because “they can’t say anything back or anything.”

Given the nuanced understanding people have of the role technology plays in their relationships, the idea of new media as a dehumanizing force is overblown. What research tells us is that technology can’t make relationships, nor can it ruin them. But technology has changed relationships. It can facilitate the development of emotional intimacy. It can lubricate sexual liaisons with strangers. It can also increase the risk of deception among intimates. All this may put an extra burden on relationships, requiring that couples do relationship work in offline as well as online spaces. Had Rick and Jessie mastered those demands, they might have been spared the years apart.

C. J. Pascoe is an assistant professor at the University of Oregon, where she teaches courses on sexuality, gender, and youth. She is the author of Dude, You’re a Fag: Masculinity and Sexuality in High School (2007).