Intelligent Machines

No Man’s Sky: A Vast Game Crafted by Algorithms

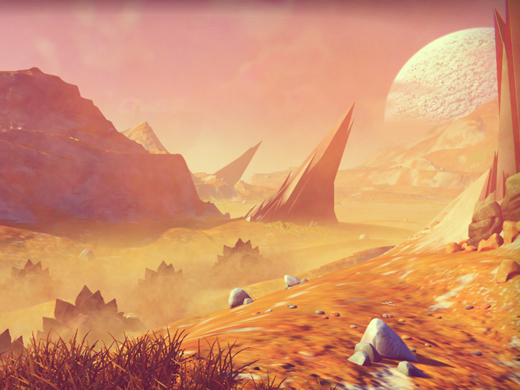

A new computer game, No Man’s Sky, demonstrates a new way to build games filled with diverse flora and fauna.

Sean Murray, one of the creators of the computer game No Man’s Sky, can’t guarantee that the virtual universe he is building is infinite, but he’s certain that, if it isn’t, nobody will ever find out. “If you were to visit one virtual planet every second,” he says, “then our own sun will have died before you’d have seen them all.”

No Man’s Sky is a video game quite unlike any other. Developed for Sony’s PlayStation 4 by an improbably small team (the original four-person crew has grown only to 10 in recent months) at Hello Games, an independent studio in the south of England, it’s a game that presents a traversable universe in which every rock, flower, tree, creature, and planet has been “procedurally generated” to create a vast and diverse play area.

“We are attempting to do things that haven’t been done before,” says Murray. “No game has made it possible to fly down to a planet, and for it to be planet-sized, and feature life, ecology, lakes, caves, waterfalls, and canyons, then seamlessly fly up through the stratosphere and take to space again. It’s a tremendous challenge.”

Procedural generation, whereby a game’s landscape is generated not by an artist’s pen but an algorithm, is increasingly prevalent in video games. Most famously Minecraft creates a unique world for each of its players, randomly arranging rocks and lakes from a limited palette of bricks whenever someone begins a new game (see “The Secret to a Video Game Phenomenon”). But No Man’s Sky is far more complex and sophisticated. The tens of millions of planets that comprise the universe are all unique. Each is generated when a player discovers it, and is subject to the laws of its respective solar systems and vulnerable to natural erosion. The multitude of creatures that inhabit the universe dynamically breed and genetically mutate as time progresses. This is virtual world building on an unprecedented scale (see video below).

This presents numerous technological challenges, not least of which is how to test a universe of such scale during its development – the team is currently using virtual testers—automated bots that wander around taking screenshots which are then sent back to the team for viewing. Additionally, while No Man’s Sky might have an infinite-sized universe, there aren’t an infinite number of players. To avoid the problem of a kind of virtual loneliness, where a player might never encounter another person on his or her travels, the game starts every new player in the same galaxy (albeit on his or her own planet) with a shared initial goal of traveling to its center. Later in the game, players can meet up, fight, trade, mine, and explore. “Ultimately we don’t know whether people will work, congregate, or disperse,” Murray says. “I know players don’t like to be told that we don’t know what will happen, but that’s what is exciting to us: the game is a vast experiment.”

The game also bears the weight of unrivaled expectation. At the E3 video game conference in Los Angeles in June, no other game met with such applause. It is the game of many childhood science fiction dreams. For Murray, that is truer than for most. He was born in Ireland, but the family lived on a farm in the Australian outback, away from civilization. “At night you could see the vastness of space,” he says. “Meanwhile, we were responsible for our own electricity and survival. We were completely cut off. It had an impact on me that I carry through life.”

Murray formed Hello Games in 2009 with three friends, all of whom had previously worked at major studios. Hello Games’ first title, Joe Danger, let players control a stuntman. The game was, according to Murray, “annoyingly successful” in the sense that it locked him and his friends into a cycle of sequels that they had formed the company to escape. During the next few years the team made four Joe Danger games for seven different platforms. “Then I had a midlife game development crisis,” says Murray. “It changes your mindset when a single game’s development represents a significant chunk of life.”

Murray decided it was time to embark upon the game he’d imagined as a child, a game about frontiership and existence on the edge of the unexplored. “We talked about the feeling of landing on a planet and effectively being the first person to discover it, not knowing what was out there,” he says. “In this era in which footage of every game is recorded and uploaded to YouTube, we wanted a game where, even if you watched every video, it still wouldn’t be spoiled for you.”

When players discover a new planet, climb that planet’s tallest peak, or identify a new species of plant or animal, they are able to upload the discovery to the game’s servers, their name forever associated with the location, like a digital Christopher Columbus or Neil Armstrong. “Players will even be able to mark the planet as toxic or radioactive, or indicate what kind of life is there and then that then appears on everyone’s map,” says Murray.

Experimentation has been a watchword throughout the game’s production. Originally the game was entirely randomly generated. “Only around 1 percent of the time would it create something that looked natural, interesting, and pleasing to the eye; the rest of the time it was a mess and, in some cases where the sky, the water, and the terrain were all the same color, unplayable,” Murray says. So the team began to create simple rules, such as the distance from a sun at which it is likely that there will be moisture,” he explains. “From that we decide there will be rivers, lakes, erosion, and weather, all of which is dependent on what the liquid is made from. The color of the water in the atmosphere will derive from what the liquid is; we model the refractions to give you a modeled atmosphere.”

Similarly, the quality of light will depend on whether the solar system has a yellow sun or, for example, a red giant or red dwarf. “These are simple rules, but combined they produce something that seems natural, recognizable to our eyes. We have come from a place where everything was random and messy to something which is procedural and emergent, but still pleasingly chaotic in the mathematical sense. Things happen with cause and effect, but they are unpredictable for us.”

At the blockbuster studios in which he once worked, 300-person teams would have to build content from scratch. Now, thanks to the increased power of PCs and video game consoles, a relatively tiny team is able to create unimaginable scope. In this sense, Hello Games may be on the cusp not only of a new universe, but also of an entirely new way of creating games. “When I look at game development in general I think the cost of creating content is the real problem,” he says. “The sheer amount of assets that artists must build to furnish a world is what forces so many safe creative bets. Likewise, you can’t have 300 people working experimentally. Game development is often more like building a skyscraper that has form and definition but is ultimately quite similar to what is around it. It never sat right with me to be in a huge warehouse with hundreds of people making a game. That is not the way it should be—and now it doesn’t have to be.”