Intelligent Machines

The Quest to Put More Reality in Virtual Reality

The inventor of Second Life has spent 15 years chasing the dream of living in virtual space. Can his new company finally give virtual worlds mass-market appeal?

Philip Rosedale is telling me about his new company, but I can’t stop myself from looking down at my hands. With palms up, I watch with fascination as I slowly wiggle my fingers and form the “OK” sign. I curl my hands into fists as I reach my arms out in front. They look pinker than normal but work as usual. When I look back up at Rosedale, he’s wearing a smile, and his eyebrows rise slightly. “Isn’t it cool?” he says. In my right ear, I hear a quiet chuckle from one of his colleagues, Ryan Karpf, standing just outside my vision.

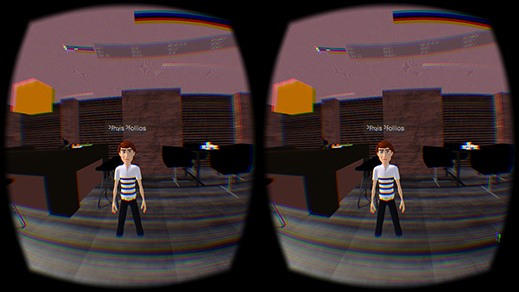

It is cool, because nothing that I’m seeing is real. Though our conversation appears to be happening in a tastefully lit club, I am actually sitting in front of a laptop in a San Francisco office wearing a virtual-reality headset and headphones. I’m trying out a new platform for virtual worlds in development by Rosedale’s startup, High Fidelity.

When I put on the virtual-reality goggles, I saw the view from my avatar’s eyes; as I moved my head, motion sensors in the goggles controlled the movements of the avatar’s head. Moving my hands in the real world controlled the avatar’s hands, thanks to an infrared motion sensor mounted on the front of the headset.

I could gesture for emphasis, and look from person to person as the conversation flowed or my attention drifted. More important, I could get a read on what Rosedale and Karpf were thinking as they spoke or listened—because their head movements and facial expressions mirrored what their real bodies were doing. Each had logged in from a laptop with a small 3-D camera perched on its screen; the camera captured their expressions, down to eye blinks and lip movements. Their virtual mouths synched with their real words. After the initial unfamiliarity wore off, chatting with Rosedale and Karpf in virtual space was much the same as it would have been in real space.

High Fidelity’s 15 employees are far from the only people thinking about virtual reality in the computing industry these days. The impressive 3-D headset being developed by startup Oculus VR, acquired by Facebook in March for $2 billion, has spurred new work on virtual-reality hardware by startups and established companies such as Sony (See “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2014: Oculus Rift”). Investors have bet $5 million that High Fidelity has worked out how to use that new technology to make a breakthrough in just how, well, real a virtual-reality experience can be. If they’re right, hanging out in virtual space will become a new form of mass-market entertainment.

Reinventing Reality

Rosedale, 46, has dreamed since he was in high school of simulating a new reality to inhabit and explore. He has worked nearly full time on it since the day in 1999 when he quit his job as chief technology officer of the Internet streaming company RealNetworks. He moved to San Francisco from Seattle and founded a company called Linden Lab. In 2003, it launched Second Life, a vast virtual space where it was up to the people logging in to build things and decide what to do. You could choose your avatar’s appearance and rent land to build castles or spaceships or beaches. You could fly and teleport.

The economic and cultural rubble of the dot-com crash was still all around. But many people were ready to believe that a new electronic medium—the “metaverse”—could transform personal and business life in improbable ways. In 2004, a media frenzy helped Second Life draw in hundreds of thousands of users and even major corporations (see “Second Earth”). People formed friendships, businesses, and extramarital relationships. Defense contractor Northrup Grumman used it for meetings and training sessions on bomb-disposal robots.

Then the excitement faded. Companies couldn’t find a business model for their Second Life operations. The simulated world was apt to unexpectedly slow to a crawl, and its system for building things was mind-numbingly complex; such technical shortcomings drove people away. “We did our best and got to a million people and made half a billion dollars [in revenue] or something,” says Rosedale, who stepped down as Linden Lab’s CEO in 2008. “But you had to have an immense amount of time and skill to get into it.”

Rosedale still logs into Second Life from time to time (his avatar is younger and slimmer than he is, with a muscled torso). So do about 1 million other people each month, and Linden Lab remains profitable. But hanging out in a free-form virtual world didn’t become mainstream, as its founders had hoped. High Fidelity is Rosedale’s attempt to use what he learned from Second Life to try once more to convince the masses to check out of the real world and into a virtual one.

Some of what his company is creating is much the same as Second Life. You download some software and then enter a virtual space where you can steer your avatar around and build stuff. This time, though, building is much easier, the lag mostly eliminated, and the graphics more impressive. As in Second Life, a digital currency (convertible into real currencies) can be used to buy things such as virtual outfits. You can earn it by offering up your spare computer processing power to other people in High Fidelity’s metaverse—a system Rosedale hopes will make it easier to corral the computing power needed to run complex simulations.

What sets High Fidelity apart from Linden Lab and other virtual-reality startups past and present is the new interface technology the company is using to make interactions with people inside its virtual world more like real life.

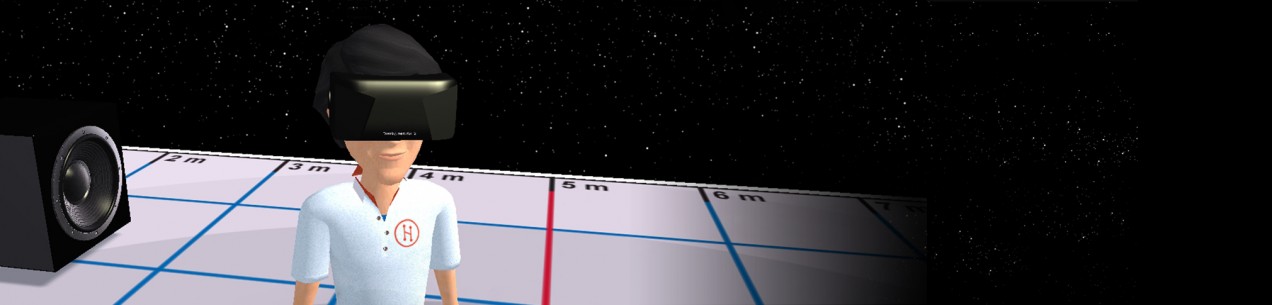

Using 3-D cameras so that your avatar copies your facial expressions is one technique (such cameras will be standard in many laptops beginning next year; see “Intel Says Laptops and Tablets with 3-D Vision Are Coming Soon”). The company is also experimenting with sensors that capture the motion of a person’s arms and hands. Some attach to the body or are held in your hands. Others, like the Leap Motion sensor attached to the Oculus headset I wore, track hands and fingers from a distance. “We want you to interact with other people in an emotionally normal way,” says Rosedale.

Jeremy Bailenson, who leads Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction lab, says that approach breaks new ground. Communication in virtual worlds has long been limited, he says, by a gap between how realistic an avatar could look and how realistically it could behave.

“Second Life had fairly realistic faces, but there was no to way to control them,” he says. “High Fidelity has solved that problem.” When he recently tried Rosedale’s technology, “the experience I got was ‘It really feels like there’s another person here,’” Bailenson says.

Rosedale thinks the possibility of such instant connection will lower the barrier to falling in love with a virtual existence, creating a new form of casual entertainment. He imagines people donning Oculus headsets to dip into quick social interactions or strange environments.

To illustrate the point, he has me put on the Oculus headset and experience a replay of a performance by a stand-up comic in High Fidelity’s virtual club. In the real world, she told jokes while a 3-D camera captured her facial expressions, and motion sensors recorded the motion of her arms. In the virtual club, an audience of High Fidelity employees chuckled along. She could see how her gags went down by watching the faces of those logged in using 3-D cameras of their own.

High Fidelity’s business model is less developed. Most of its software and platform will be open source, so anyone can use it or set up a virtual world using its technology. High Fidelity plans to make money by charging people to include their worlds in a kind of directory for the metaverse, similar to the domain name system for the Web. For now, it is offering up an early version of that free to the couple of hundred people already building their own worlds in an invite-only alpha trial. In the next few months, that program will be open to anyone.

Rosedale is excited about that, but he doesn’t have the air of a businessman smelling a trail to profit. He’s genuinely convinced that virtual worlds will open up a new era of human existence. “Why go into outer space when it’s more likely that by amassing computing resources we will create all the mysteries and unknowns and new species inside them?” he says. Rosedale says the freedom to explore and experiment inside a virtual world generates a “social force,” creating positive interactions between people that are impossible in everyday life–much like the Burning Man festival he attends each year. It’s a vision that betrays a touching if naïve faith in humans and technology. But it’s set Rosedale on a shared course with some of the biggest names in technology.

Virtual Facebook

There’s good reason to be skeptical that millions of people will begin living some of their lives in virtual space. Virtual reality has overpromised and underdelivered for around 30 years, and its prophets have repeatedly persuaded outsiders to believe claims of assured success that turned out to be false. High Fidelity has impressive demos but no finished product. When I met Rosedale in that virtual club, his avatar’s eyes sometimes darted wildly to the side because of glitches with the face-tracking technology.

But Rosedale has picked a good time to test his ideas again. Though the hysteria hasn’t reached the levels of 2005, popular enthusiasm about virtual worlds is surging again thanks to Oculus. Huge expectations await the consumer version of the Rift goggles, due by 2016, and competing products in development by Sony and Samsung. All are expected to retail for only hundreds of dollars. Journalists and software developers have had enough access to prototypes to be convinced that the basic technical problem with virtual reality—how to fool the human visual system into perceiving virtual space as real—is nearly solved. Whether this new hardware will lead to anything beyond extra-immersive video games is unclear, but the field is more open to new ideas than it has been for a long time. This week, news broke that Google had led a group of influential Silicon Valley investors that put $542 million into Magic Leap, a startup working on hardware for augmented and virtual reality.

On a conference call after his company bought Oculus, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg called Oculus Rift the “next major computing platform.” And he hinted that ideas like those propelling Rosedale are the reason why. “Imagine sharing not just moments with your friends online, but entire experiences and adventures,” he said.

Rosedale’s faith in a mass-market metaverse has held strong for nearly 15 years. Now the world and the necessary technology may have finally caught up. When I ask him how that feels, Rosedale smiles broadly and gets a faraway look, but the significance of it seems to leave him lost for words.

Advertisement