Business Impact

3-D-Printed Sneakers, Tailored to Your Foot

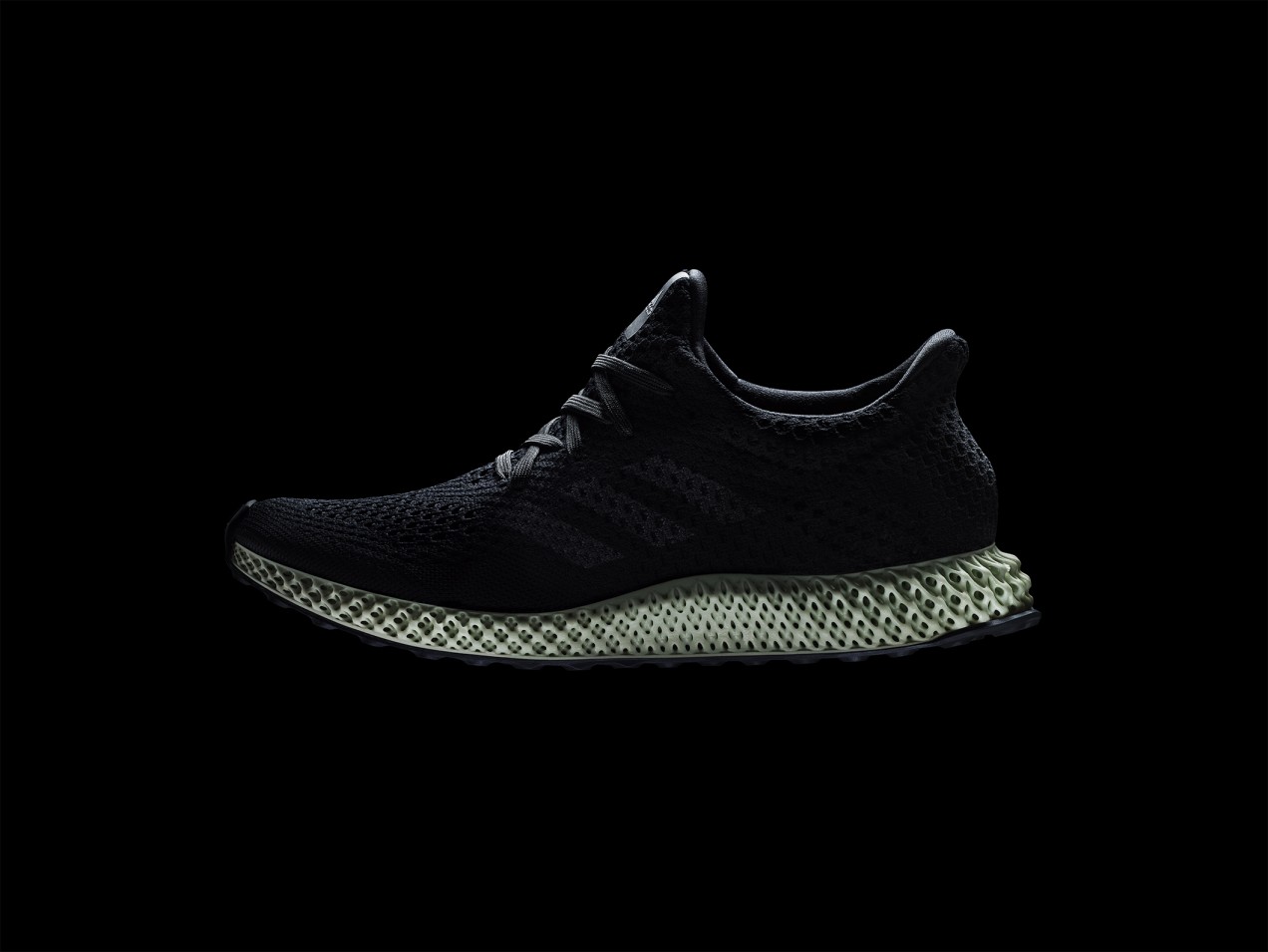

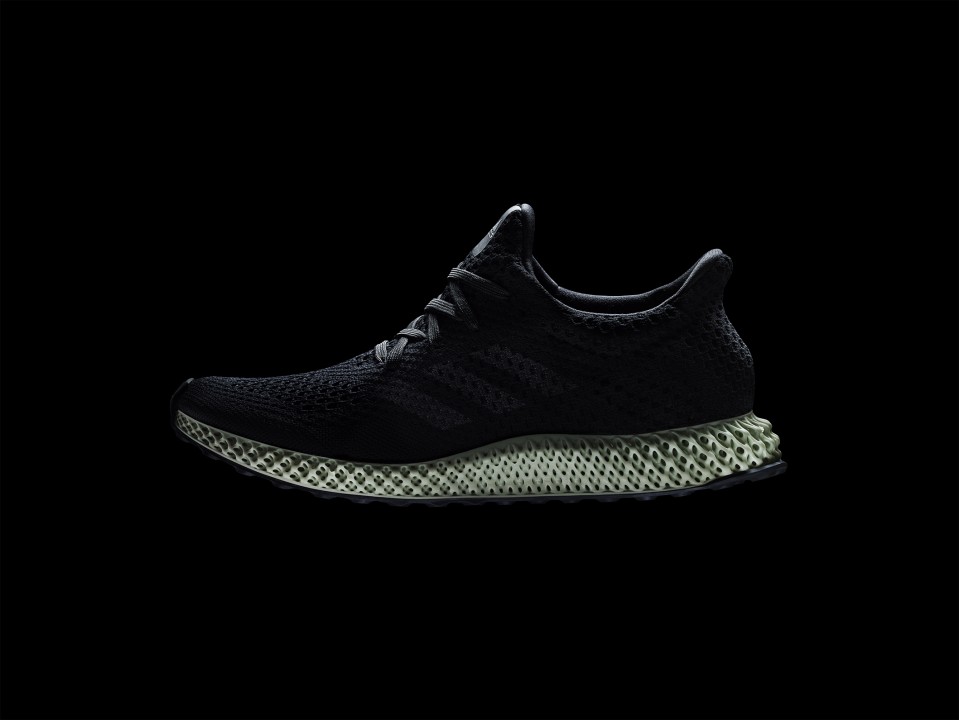

Throw out your custom insoles. Adidas is selling shoes with soles that will soon include bespoke shock absorbers.

Proponents of 3-D printing have long talked about the possibility of using the technology to customize consumer products. One of the most oft-cited possibilities is printing sneakers with soles tailored to individual runner’s biometrics or to the quirks of each couch potato’s arches.

Today, Bay Area 3-D-printing company Carbon announced that it has made that happen. Carbon has been working with the apparel company Adidas to develop materials and designs for athletic-shoe midsoles, the squishy, shock-absorbing part of the sneaker. Adidas will sell FutureCraft 4D shoes with midsoles printed on Carbon’s machines, starting with 300 promotional pairs this month at an undisclosed price. It promises that 5,000 will be available at retail outlets later in the year. Adidas will produce millions of midsoles by 2018—which Carbon says makes this the largest-scale production of a 3-D-printed product so far.

The first product won’t be individually tailored, but that’s in the works. Adidas will soon begin using Carbon’s printers at distributed manufacturing centers, where the company will make bespoke shoes for local customers. Adidas opened a pilot “Speedfactory” in the German city of Herzogenaurach in December 2015; the company plans to open one in Atlanta this year.

Carbon, originally called Carbon 3D, was cofounded by chemical engineer Joseph DeSimone in 2013 to commercialize his research on materials and processes for faster 3-D printing using high-performance polymers (see “Speeding Up 3-D Printing”). DeSimone, who won the Lemelson-MIT Prize in 2008 and has worked on materials for stents, nanomedicine, and many other applications, is currently on leave from a faculty position at the University of North Carolina to serve as the company’s CEO.

Though the initial line of shoes will be made in a centralized facility and will not be individually tailored, DeSimone says Adidas was able to take advantage of 3-D printing to create a shock-absorbing, multilayer structure that can’t be made using injection molding. The process also allows for the properties of the midsole to vary along its length, with different levels of stiffness at the heel, for example.

The midsole has a honeycomb structure. “Mechanical engineers have been taunting the world with the properties of these structures for years,” says DeSimone. “You can’t injection-mold something like that, because each strut is an individual piece.”

Julia Greer, a Caltech materials scientist and mechanical engineer who studies the effects of micro- and nanoscale structure on the properties of materials (a job that involves taunting us with many wonderful structures), says honeycomb geometries are promising for shock absorption and durability. When such a structure is stressed, it will deform only in the direction of the stress, Greer explains. So as your heel strikes the midsole, it should compress toward the ground, absorbing the stress, but it should not bulge out at the sides, potentially wearing out the shoe.

It currently takes 90 minutes to print a single insole; Carbon is working with Adidas to develop machinery to speed this up to 20 minutes. Carbon’s printers use patterned laser light to print continuously out of a liquid bath of polymer “ink.” The continuous process, which makes the printers fast, is possible because the printing baths maintain an oxygen barrier at the bottom that prevents the solidified polymer from sticking. Continuous printing also means the parts are uniform, compared with other technologies that print one layer at a time. The layer-by-layer approach can cause mechanical weakness at the interfaces between the layers—something Carbon’s process avoids. Carbon has also focused on chemical engineering of polymers. For the Adidas collaboration, the company tailored a printable elastomer with the right mechanical properties and colors for the shoe.

Adidas designers worked in-house at Carbon on about 50 iterations of the final design. Usually, designers are only able to go through about five such steps, because each iteration must be made and tooled before returning to the designer’s hands, and that can take weeks. DeSimone says being able to design and test products where they are fabricated, with a 3-D printer, means “the end of prototyping.”

Advertisement