Lifting the Fog

A fog dissipator invented by Henry Houghton, SM ’27, helped establish the field of cloud physics.

In 1933, an airship hangar on the Round Hill estate in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, housed MIT’s newest creation—a 40-foot-tall Van de Graaff generator capable of producing more than five million volts of electricity. As researchers flocked to MIT’s Round Hill research station to observe as it accelerated subatomic particles to extreme speeds, one of them was more interested in a different kind of particle.

Research associate Henry Garrett Houghton Jr., SM ’27, an electrical engineer hired to study electromagnetic wave transmission through fog, was fascinated by the low clouds that billowed over Round Hill whenever warm air met the cool water of nearby Buzzards Bay. Long a serious obstacle to navigation at sea, fog also made landing planes difficult. Having witnessed treacherous fog at Round Hill’s tiny airport, Houghton considered it “the greatest hindrance to the development of aviation.” He also thought combatting fog would prove that humans could use science to modify weather, and maybe in the very distant future even control it.

In the late 1920s, Houghton began investigating how light travels through fog. His results varied from experiment to experiment and were inconsistent with work from other researchers, including future MIT president Julius A. Stratton ’23, SM ’26, who was also at Round Hill, studying fog’s impact on electromagnetic waves. Houghton concluded that the variations weren’t in the experiment design but in the fog itself. While researchers widely assumed that fog particles were uniform in size, he thought that size variations might account for the inconsistent light penetration.

Houghton and Stratton coated microscope slides with clear grease, allowed fog to drift over them, and then measured and photographed droplets caught on the surface. Confirming that droplets weren’t uniform, Houghton studied their chemical composition and found that Round Hill’s fog contained small amounts of sea salt, which attracted evaporated water molecules, increasing humidity in the air near sea level. When warm air fronts came through, this humidified air condensed, forming low-lying clouds that swelled over the estate.

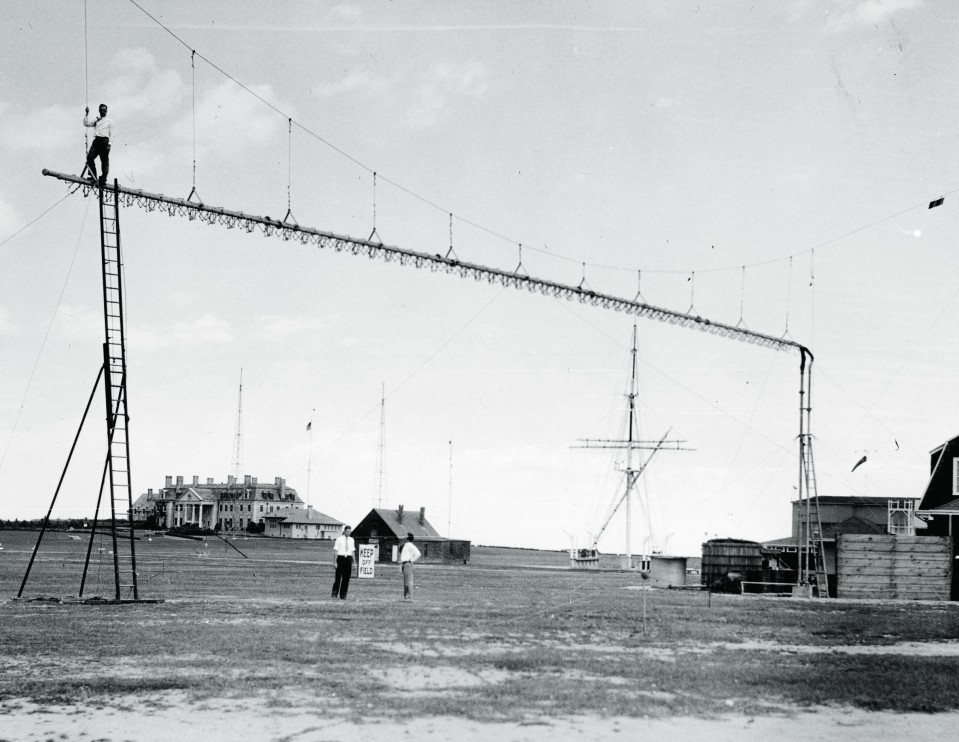

Houghton hypothesized that if a more moisture-absorbing chemical were introduced to the fog, water molecules would attach to the new compound, vapor pressure would drop, and the fog would dissipate. He scattered calcium chloride, an inexpensive compound with such properties, onto a dense layer of artificial fog and watched as the fog vanished. Field trials in which a calcium chloride solution was sprayed onto natural fog yielded similar results, but the technique wasn’t practical for clearing fog from sizable patches of land. To do that, and to counteract the way the wind pushed new fog in, Houghton suspended a 100- foot-long pipeline with downward-facing spray nozzles from 30 feet in the air. When set up perpendicular to wind direction, the apparatus shot a misty curtain of calcium chloride toward the ground, dispersing any fog rolling through. Spraying 2.5 gallons of the compound per second, Houghton’s machine took only three minutes to turn an area with visibility of less than 500 feet into one where “buildings more than a quarter-mile away were visible,” according to one report. His 1934 demonstration was viewed as one of the earliest successful examples of weather manipulation. (In the early 1920s, Cornell University chemistry professor Wilder D. Bancroft and self-taught inventor L. Francis Warren had scattered electrified sand from a plane, forming holes in—or sometimes completely dissipating—fair-weather clouds as their moisture particles condensed and fell from the sky. But despite claims that the technique could one day create rain on demand, results weren’t consistent and never translated to large-scale weather modification; nor did it work for ground-level fog.)

Houghton tried to adapt his fog dispeller for airports or even planes themselves, but it was impractical for commercial use because it required so much calcium chloride, which has corrosive properties. Though it wasn’t the aviation breakthrough he’d envisioned, his fog dissipation research did lead to advancements in plane deicing and helped establish a new research field called cloud physics, which explores atmospheric condensation and precipitation. Houghton eventually became head of MIT’s Department of Meteorology and fought to increase funding for basic research, telling the First National Conference on Applied Meteorology in 1957 that weather was increasingly a national security priority in the context of the Cold War. “I shudder to think of the consequences of a prior Russian discovery of a feasible method of weather control,” Houghton said, although he’d previously been a voice of moderation on the plausibility of weather control. “International control of weather modification will be essential in the safety of the world as control of nuclear energy now is.”