Tech Policy / Privacy

Who needs democracy when you have data?

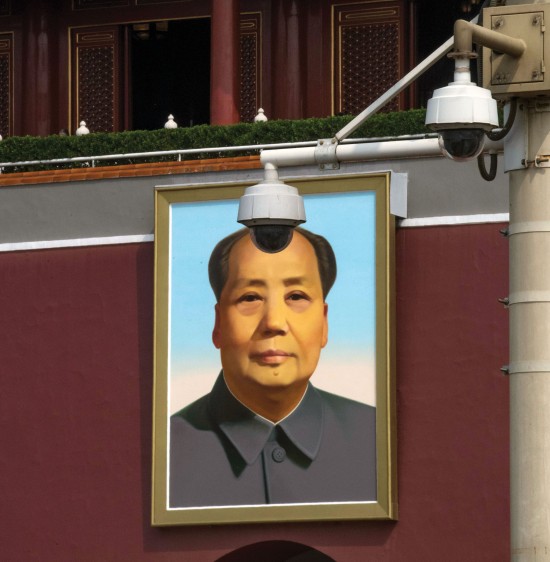

Here’s how China rules using data, AI, and internet surveillance.

In 1955, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov published a short story about an experiment in “electronic democracy,” in which a single citizen, selected to represent an entire population, responded to questions generated by a computer named Multivac. The machine took this data and calculated the results of an election that therefore never needed to happen. Asimov’s story was set in Bloomington, Indiana, but today an approximation of Multivac is being built in China.

For any authoritarian regime, “there is a basic problem for the center of figuring out what’s going on at lower levels and across society,” says Deborah Seligsohn, a political scientist and China expert at Villanova University in Philadelphia. How do you effectively govern a country that’s home to one in five people on the planet, with an increasingly complex economy and society, if you don’t allow public debate, civil activism, and electoral feedback? How do you gather enough information to actually make decisions? And how does a government that doesn’t invite its citizens to participate still engender trust and bend public behavior without putting police on every doorstep?

Hu Jintao, China’s leader from 2002 to 2012, had attempted to solve these problems by permitting a modest democratic thaw, allowing avenues for grievances to reach the ruling class. His successor, Xi Jinping, has reversed that trend. Instead, his strategy for understanding and responding to what is going on in a nation of 1.4 billion relies on a combination of surveillance, AI, and big data to monitor people’s lives and behavior in minute detail.

It helps that a tumultuous couple of years in the world’s democracies have made the Chinese political elite feel increasingly justified in shutting out voters. Developments such as Donald Trump’s election, Brexit, the rise of far-right parties across Europe, and Rodrigo Duterte’s reign of terror in the Philippines underscore what many critics see as the problems inherent in democracy, especially populism, instability, and precariously personalized leadership.

Since becoming general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, Xi has laid out a raft of ambitious plans for the country, many of them rooted in technology—including a goal to become the world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030. Xi has called for “cyber sovereignty” to enhance censorship and assert full control over the domestic internet. In May, he told a meeting of the Chinese Academy of Sciences that technology was the key to achieving “the great goal of building a socialist and modernized nation.” In January, when he addressed the nation on television, the bookshelves on either side of him contained both classic titles such as Das Kapital and a few new additions, including two books about artificial intelligence: Pedro Domingos’s The Master Algorithm and Brett King’s Augmented: Life in the Smart Lane.

“No government has a more ambitious and far-reaching plan to harness the power of data to change the way it governs than the Chinese government,” says Martin Chorzempa of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, DC. Even some foreign observers, watching from afar, may be tempted to wonder if such data-driven governance offers a viable alternative to the increasingly dysfunctionallooking electoral model. But over-relying on the wisdom of technology and data carries its own risks.

Data instead of dialogue

Chinese leaders have long wanted to tap public sentiment without opening the door to heated debate and criticism of the authorities. For most of imperial and modern Chinese history, there has been a tradition of disgruntled people from the countryside traveling to Beijing and staging small demonstrations as public “petitioners.” The thinking was that if local authorities didn’t understand or care about their grievances, the emperor might show better judgment.

Under Hu Jintao, some members of the Communist Party saw a limited openness as a possible way to expose and fix certain kinds of problems. Blogs, anticorruption journalists, human-rights lawyers, and online critics spotlighting local corruption drove public debate toward the end of Hu’s reign. Early in his term, Xi received a daily briefing of public concerns and disturbances scraped from social media, according to a former US official with knowledge of the matter. In recent years, petitioners have come to the capital to draw attention to scandals such as illegal land seizures by local authorities and contaminated milk powder.

But police are increasingly stopping petitioners from ever reaching Beijing. “Now trains require national IDs to purchase tickets, which makes it easy for the authorities to identify potential ‘troublemakers’ such as those who have protested against the government in the past,” says Maya Wang, senior China researcher for Human Rights Watch. “Several petitioners told us they have been stopped at train platforms.” The bloggers, activists, and lawyers are also being systematically silenced or imprisoned, as if data can give the government the same information without any of the fiddly problems of freedom.

The idea of using networked technology as a tool of governance in China goes back to at least the mid-1980s. As Harvard historian Julian Gewirtz explains, “When the Chinese government saw that information technology was becoming a part of daily life, it realized it would have a powerful new tool for both gathering information and controlling culture, for making Chinese people more ‘modern’ and more ‘governable’—which have been perennial obsessions of the leadership.” Subsequent advances, including progress in AI and faster processors, have brought that vision closer.

As far as we know, there is no single master blueprint linking technology and governance in China. But there are several initiatives that share a common strategy of harvesting data about people and companies to inform decision-making and create systems of incentives and punishments to influence behavior. These initiatives include the State Council’s 2014 “Social Credit System,” the 2016 Cybersecurity Law, various local-level and private-enterprise experiments in “social credit,” “smart city” plans, and technology-driven policing in the western region of Xinjiang. Often they involve partnerships between the government and China’s tech companies.

The most far-reaching is the Social Credit System, though a better translation in English might be the “trust” or “reputation” system. The government plan, which covers both people and businesses, lists among its goals the “construction of sincerity in government affairs, commercial sincerity, and judicial credibility.” (“Everybody in China has an auntie who’s been swindled. There is a legitimate need to address a breakdown in public trust,” says Paul Triolo, head of the geotechnology practice at the consultancy Eurasia Group.) To date, it’s a work in progress, though various pilots preview how it might work in 2020, when it is supposed to be fully implemented.

Blacklists are the system’s first tool. For the past five years, China’s court system has published the names of people who haven’t paid fines or complied with judgments. Under new social-credit regulations, this list is shared with various businesses and government agencies. People on the list have found themselves blocked from borrowing money, booking flights, and staying at luxury hotels. China’s national transport companies have created additional blacklists, to punish riders for behavior like blocking train doors or picking fights during a journey; offenders are barred from future ticket purchases for six or 12 months. Earlier this year, Beijing debuted a series of blacklists to prohibit “dishonest” enterprises from being awarded future government contracts or land grants.

A few local governments have experimented with social-credit “scores,” though it’s not clear if they will be part of the national plan. The northern city of Rongcheng, for example, assigns a score to each of its 740,000 residents, Foreign Policy reported. Everyone begins with 1,000 points. If you donate to a charity or win a government award, you gain points; if you violate a traffic law, such as by driving drunk or speeding through a crosswalk, you lose points. People with good scores can earn discounts on winter heating supplies or get better terms on mortgages; those with bad scores may lose access to bank loans or promotions in government jobs. City Hall showcases posters of local role models, who have exhibited “virtue” and earned high scores.

“The idea of social credit is to monitor and manage how people and institutions behave,” says Samantha Hoffman of the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. “Once a violation is recorded in one part of the system, it can trigger responses in other parts of the system. It’s a concept designed to support both economic development and social management, and it’s inherently political.” Some parallels to parts of China’s blueprint already exist in the US: a bad credit score can prevent you from taking out a home loan, while a felony conviction suspends or annuls your right to vote, for example. “But they’re not all connected in the same way—there’s no overarching plan,” Hoffman points out.

One of the biggest concerns is that because China lacks an independent judiciary, citizens have no recourse for disputing false or inaccurate allegations. Some have found their names added to travel blacklists without notification after a court decision. Petitioners and investigative journalists are monitored according to another system, and people who’ve entered drug rehab are watched by yet a different monitoring system. “Theoretically the drug-user databases are supposed to erase names after five or seven years, but I’ve seen lots of cases where that didn’t happen,” says Wang of Human Rights Watch. “It’s immensely difficult to ever take yourself off any of these lists.”

Occasional bursts of rage online point to public resentment. News that a student had been turned down by a college because of her father’s inclusion on a credit blacklist recently lit a wildfire of online anger. The college’s decision hadn’t been officially sanctioned or ordered by the government. Rather, in their enthusiasm to support the new policies, school administrators had simply taken them to what they saw as the logical conclusion.

The opacity of the system makes it difficult to evaluate how effective experiments like Rongcheng’s are. The party has squeezed out almost all critical voices since 2012, and the risks of challenging the system—even in relatively small ways—have grown. What information is available is deeply flawed; systematic falsification of data on everything from GDP growth to hydropower use pervades Chinese government statistics. Australian National University researcher Borge Bakken estimates that official crime figures, which the government has a clear incentive to downplay, may represent as little as 2.5 percent of all criminal behavior.

In theory, data-driven governance could help fix these issues—circumventing distortions to allow the central government to gather information directly. That’s been the idea behind, for instance, introducing air-quality monitors that send data back to central authorities rather than relying on local officials who may be in the pocket of polluting industries. But many aspects of good governance are too complicated to allow that kind of direct monitoring and instead rely on data entered by those same local officials.

However, the Chinese government rarely releases performance data that outsiders might use to evaluate these systems. Take the cameras that are used to identify and shame jaywalkers in some cities by projecting their faces on public billboards, as well as to track the prayer habits of Muslims in western China. Their accuracy remains in question: in particular, how well can facial-recognition software trained on Han Chinese faces recognize members of Eurasian minority groups? Moreover, even if the data collection is accurate, how will the government use such information to direct or thwart future behavior? Police algorithms that predict who is likely to become a criminal are not open to public scrutiny, nor are statistics that would show whether crime or terrorism has grown or diminished. (For example, in the western region of Xinjiang, the available information shows only that the number of people taken into police custody has shot up dramatically, rising 731 percent from 2016 to 2017.)

“It’s not the technology that created the policies, but technology greatly expands the kinds of data that the Chinese government can collect on individuals,” says Richard McGregor, a senior fellow at the Lowy Institute and the author of The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers. “The internet in China acts as a real-time, privately run digital intelligence service.”

Algorithmic policing

Writing in the Washington Post earlier this year, Xiao Qiang, a professor of communications at the University of California, Berkeley, dubbed China’s data-enhanced governance “a digital totalitarian state.” The dystopian aspects are most obviously on display in western China.

Xinjiang (“New Territory”) is the traditional home of a Chinese Muslim minority known as Uighurs. As large numbers of Han Chinese migrants have settled in—some say “colonized”—the region, the work and religious opportunities afforded to the local Uighur population have diminished. One result has been an uptick in violence in which both Han and Uighur have been targeted, including a 2009 riot in the capital city of Urumqi, when a reported 200 people died. The government’s response to rising tensions has not been to hold public forums to solicit views or policy advice. Instead, the state is using data collection and algorithms to determine who is “likely” to commit future acts of violence or defiance.

The Xinjiang government employed a private company to design the predictive algorithms that assess various data streams. There’s no public record or accountability for how these calculations are built or weighted. “The people living under this system generally don’t even know what the rules are,” says Rian Thum, an anthropologist at Loyola University who studies Xinjiang and who has seen government procurement notices that were issued in building the system.

In the western city of Kashgar, many of the family homes and shops on main streets are now boarded up, and the public squares are empty. When I visited in 2013, it was clear that Kashgar was already a segregated city—the Han and Uighur populations lived and worked in distinct sections of town. But in the evenings, it was also a lively and often noisy place, where the sounds of the call to prayer intermingled with dance music from local clubs and the conversations of old men sitting out late in plastic chairs on patios. Today the city is eerily quiet; neighborhood public life has virtually vanished. Emily Feng, a journalist for the Financial Times, visited Kashgar in June and posted photos on Twitter of the newly vacant streets.

The reason is that by some estimates more than one in 10 Uighur and Kazakh adults in Xinjiang have been sent to barbed-wire-ringed “reeducation camps”—and those who remain at large are fearful.

In the last two years thousands of checkpoints have been set up at which passersby must present both their face and their national ID card to proceed on a highway, enter a mosque, or visit a shopping mall. Uighurs are required to install government-designed tracking apps on their smartphones, which monitor their online contacts and the web pages they’ve visited. Police officers visit local homes regularly to collect further data on things like how many people live in the household, what their relationships with their neighbors are like, how many times people pray daily, whether they have traveled abroad, and what books they have.

All these data streams are fed into Xinjiang’s public security system, along with other records capturing information on everything from banking history to family planning. “The computer program aggregates all the data from these different sources and flags those who might become ‘a threat’ to authorities,” says Wang. Though the precise algorithm is unknown, it’s believed that it may highlight behaviors such as visiting a particular mosque, owning a lot of books, buying a large quantity of gasoline, or receiving phone calls or email from contacts abroad. People it flags are visited by police, who may take them into custody and put them in prison or in reeducation camps without any formal charges.

Adrian Zenz, a political scientist at the European School of Culture and Theology in Korntal, Germany, calculates that the internment rate for minorities in Xinjiang may be as high as 11.5 percent of the adult population. These camps are designed to instill patriotism and make people unlearn religious beliefs. (New procurement notices for cremation security guards seem to indicate that the government is also trying to stamp out traditional Muslim burial practices in the region.)

While Xinjiang represents one draconian extreme, elsewhere in China citizens are beginning to push back against some kinds of surveillance. An internet company that streamed closed-circuit TV footage online shut down those broadcasts after a public outcry. The city of Shanghai recently issued regulations to allow people to dispute incorrect information used to compile social-credit records. “There are rising demands for privacy from Chinese internet users,” says Samm Sacks, a senior fellow in the Technology Policy Program at CSIS in New York. “It’s not quite the free-for-all that it’s made out to be.”

Christina Larson is an award-winning foreign correspondent and science journalist, writing mostly about China and Asia.