Climate Change / Clean Energy

China’s losing its taste for nuclear power. That’s bad news.

Once nuclear’s strongest booster, China is growing wary about its cost and safety.

“Most beautiful wedding photos taken at a nuclear power plant” might just be the strangest competition ever. But by inviting couples to celebrate their nuptials at the Daya Bay plant in Shenzhen and post the pictures online, China General Nuclear Power (CGN), the country’s largest nuclear power operator, got lots of favorable publicity.

A year later, the honeymoon is over.

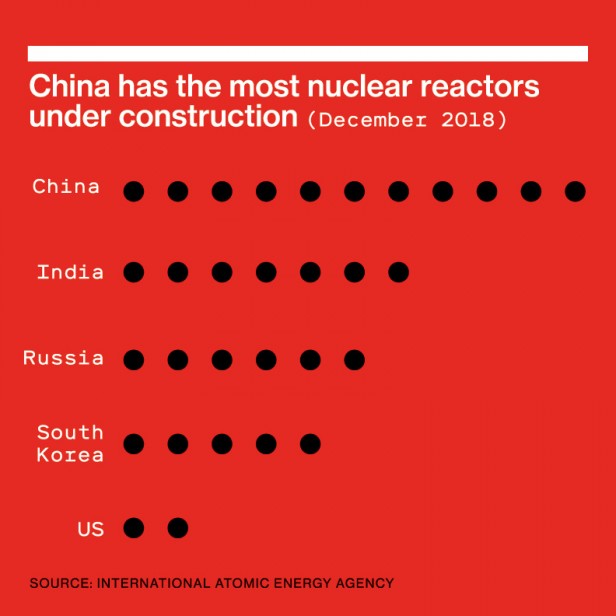

For years, as other countries have shied away from nuclear power, China has been its strongest advocate. Of the four reactors that started up worldwide in 2017, three were in China and the fourth was built by Beijing-based China National Nuclear Corp. (CNNC) in Pakistan. China’s domestic nuclear generation capacity grew by 24% in the first 10 months of 2018.

The country has the capacity to build 10 to 12 nuclear reactors a year. But though reactors begun several years ago are still coming online, the industry has not broken ground on a new plant in China since late 2016, according to a recent World Nuclear Industry Status Report.

Officially China still sees nuclear power as a must-have. But unofficially, the technology is on a death watch. Experts, including some with links to the government, see China’s nuclear sector succumbing to the same problems affecting the West: the technology is too expensive, and the public doesn’t want it.

The 2011 meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi plant shocked Chinese officials and made a strong impression on many Chinese citizens. A government survey in August 2017 found that only 40% of the public supported nuclear power development.

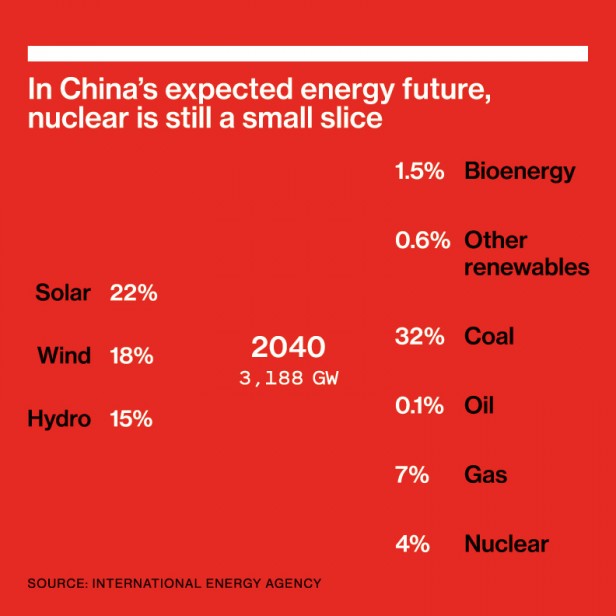

The bigger problem is financial. Reactors built with extra safety features and more robust cooling systems to avoid a Fukushima-like disaster are expensive, while the costs of wind and solar power continue to plummet: they are now 20% cheaper than electricity from new nuclear plants in China, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Moreover, high construction costs make nuclear a risky investment.

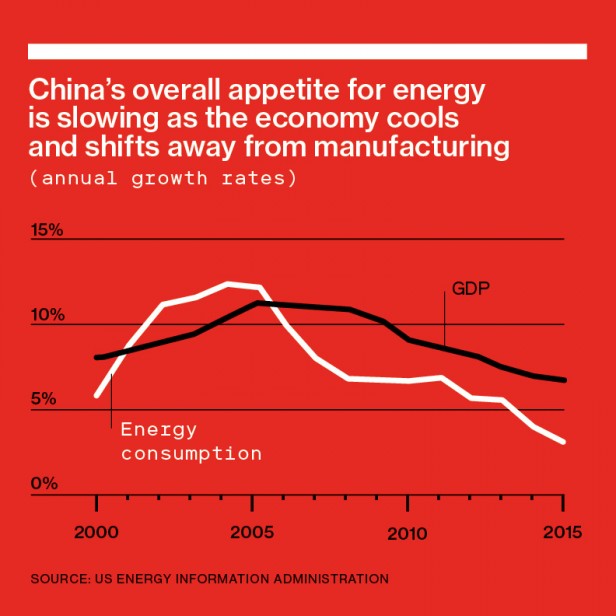

And gone are the days when nuclear power was desperately needed to meet China’s soaring demand for electricity. In the early 2000s, power consumption was growing at more than 10% annually as the economy boomed and manufacturing, a heavy user of electricity, expanded rapidly. Over the past few years, as growth has slowed and the economy has diversified, power demand has been growing, on average, at less than 4%.

China’s disenchantment with nuclear power corresponds with an overall decline in nuclear generation elsewhere in the world. Utilities are retiring existing plants and have stopped building new ones. If China, too, gives up on nuclear, it could sound the death knell for a steady, carbon-free energy source that many see as crucial to slowing climate change.

Fukushima changed everything

China’s energy planners launched its nuclear industry in the 1980s with the construction of plants like Daya Bay. In 2005 the country began a massive building spree that was intended to solve persistent energy shortages and combat worsening air pollution from the country’s numerous coal plants. By 2009, government planners expected 2020 nuclear capacity to be 10 times what it was in 2005.

Then the Fukushima disaster happened. China’s leaders watched in shock as the biggest utility in one of the world’s most advanced industrial countries proved powerless to prevent a series of meltdowns. They knew that if a similar accident occurred in China, the damage wouldn’t be limited to the explosion and nuclear fallout. Such an event would call into question the government’s competence. “If an event like Fukushima punctures that image of competence, that’s very, very consequential,” says William Overholt, a China expert at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. “That would delegitimize the regime.”

Within days of Fukushima, nuclear reactor construction in China was frozen. When building resumed months later, after a wave of inspections, Beijing insisted that future nuclear power projects adopt more advanced designs with extra safety features.

The damage to public confidence, however, had already been done. In 2013 over a thousand people assembled in Jiangmen, east of Hong Kong, to decry a planned uranium fuel plant. Within days the state-run project was scrapped. In 2016 local officials suspended preliminary work on a site in Lianyungang, in northeastern Jiangsu province, after an uproar caused by revelations that it might host a recycling plant for spent nuclear fuel. In the wake of that protest, China’s State Council amended its draft regulations on nuclear power management, requiring developers to hold public hearings before siting projects.

Sticker shock

Last June two of the world’s most advanced reactors began operating in China: a US-designed AP1000 and a French-German EPR. In theory, these reactors are at greatly reduced risk of a Fukushima-style accident. At the Japanese plant, tsunami waves swamped the backup generators needed to keep coolant pumps running, and the catastrophic loss of coolant caused three of the plant’s six reactors to melt down. The AP1000 design stores water above the reactor that can be gravity-fed to keep it cool if the pumps fail. The EPR reactors employ multiple redundant generators and cooling systems to lower meltdown risk.

But adding safety adds cost. At 52.5 billion yuan ($7.6 billion) for an AP1000 plant with the typical configuration of two reactors, the construction cost is nearly double that of the conventional technology commonly used in China. Wenke Han, a former head of the Energy Research Institute, an arm of the powerful National Development and Reform Commission that plans China’s economy, calls nuclear power “very expensive.” He adds, “Nuclear power in China has begun to face price competition, and will certainly face more competition in the future.”

Coal remains the cheapest source of power in China, but grid operators face demands from the government to use more renewable energy to limit air pollution. With pressure from both directions, even the nuclear plants now operating are underutilized. On average they used 81% of their generating capacity in 2017, 10% less than five years earlier, making the electricity they produce even more expensive.

Dwindling options

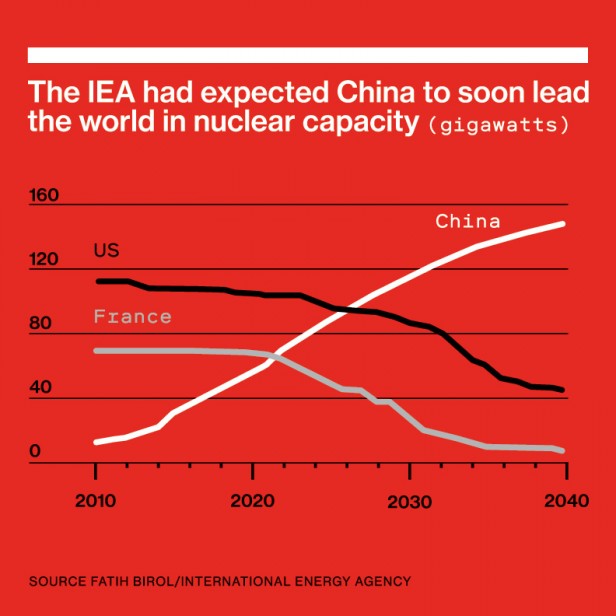

The government has lately said little about nuclear policy. Its official target, last updated in 2016, calls for 58 gigawatts of nuclear generating capacity to be installed by 2020 and for another 30 GW to be under construction. All experts agree China won’t reach its 2020 goal until 2022 or later, and pre-Fukushima projections of 400 GW or more by midcentury now look fanciful. Han says he is betting that after the country builds the 88 GW in its 2020 plan, it will move on to other energy sources.

Others believe that China will continue building reactors but at a slower pace than in the past. The country is developing its own advanced design, the Hualong One, and may want to protect the nuclear industry, including its nascent efforts to export the new reactor. CNNC is building two in Pakistan, and CGN is seeking design approval in the UK. CNNC is also building two at its Fuqing power plant in southeastern Fujian province. Construction began in 2015, and CNNC says it will have one reactor operating in 2019, ahead of schedule.

If the Hualong One proves too expensive, China’s lingering nuclear hopes will be pinned to its advanced-reactor program—an effort to develop a new generation of technologies that include high-temperature gas-cooled reactors, designs cooled with sodium metal or salt, and smaller versions of pressurized-water reactors. These various designs are meant to be cheaper to build and operate—and much safer—than conventional reactors.

But so far there is little evidence that any of them will solve nuclear’s problems. A sodium-cooled reactor completed near Beijing in 2011 has had familiar technical glitches such as problems in its coolant systems. And the rising cost of a pair of high-temperature gas-cooled reactors nearing completion at Shandong Province’s Shidao Bay ended plans for a further 18 such reactors at the site.

There’s always the possibility of a breakthrough that would make nuclear safe and cheap enough to compete with renewables and coal. But even China’s nuclear giants are hedging their bets. Both CGN and the state-owned firm funding China’s AP1000 investments rank among the world’s top 10 renewable-power operators.

Shifting toward renewables and away from nuclear may be a sound business strategy for these companies. But it could mean one less carbon-free option for a world facing the threat of climate change. If China’s nuclear ambitions wind down, it may be the nail in the coffin for the technology’s viability elsewhere.

Peter Fairley is a freelance energy journalist based in San Francisco and Victoria, BC.