Biotechnology

Opioid overdoses could be prevented by an app that listens to breathing

Many overdoses don’t have to be fatal if they’re caught in time. A new app can identify when you might be in trouble and call for help.

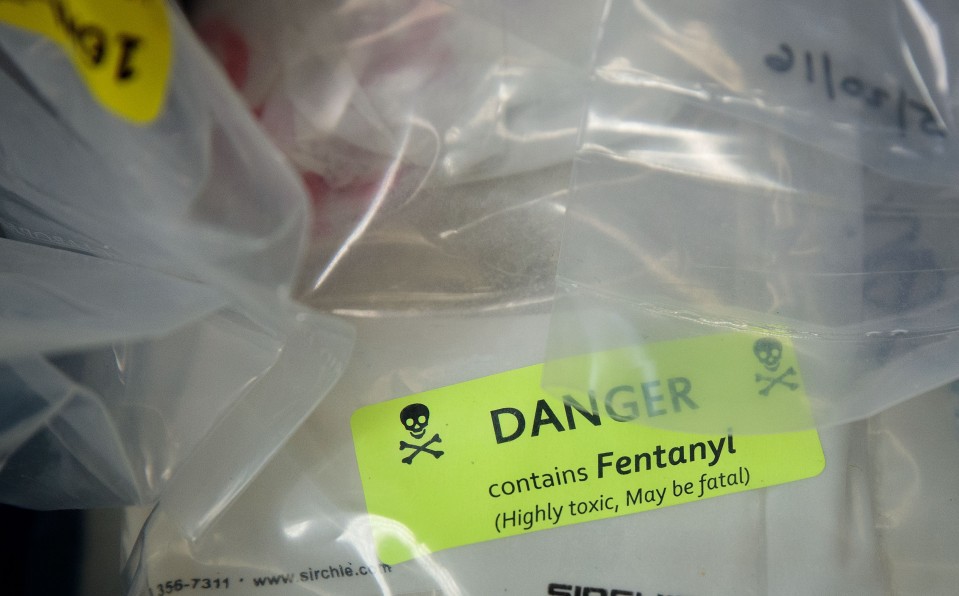

The opioid epidemic in the US kills 115 Americans every day, with fentanyl by far the biggest killer. Per year, drugs in the US are deadlier than gun violence or car crashes. But if caught in time, opioid overdoses are entirely reversible. A new smartphone app might one day help save lives by identifying people when they have overdosed—and then calling their family or emergency services for help.

The system, developed by a team from the University of Washington, effectively converts a phone into a sonar device using the built-in speaker and microphone. An algorithm analyzes the rate of reflected sound waves to identify if someone’s breathing has slowed or stopped (apnea), or if the person isn’t moving—all of which could signal that an overdose has started.

The system was tested on 194 participants using heroin, fentanyl, or morphine in a supervised injection facility in Vancouver. It managed to accurately identify apnea 97.7% of the time and slow breathing 89.3% of the time. All participants who overdosed were resuscitated by onsite staff.

The app also managed to spot 19 out of 20 simulated overdoses in an operating room, where anesthetics were used to mimic the problem. The results were published in Science Translational Medicine today.

“For a user, all they will have to do is turn the app on, press a button, and it will monitor their breathing, then notify their loved ones if they get into difficulty,” says coauthor Rajalakshmi Nandakumar. In the tests the phone was within a meter of the user, and the app was able to adjust if the phone was moved or if the user’s posture changed.

The team hopes to integrate the app with 911 and emergency services so help can get to people who’ve overdosed as quickly as possible. It has also applied to get approval from the US Food and Drug Administration so it can spin the technology out into a company.

The app has proved popular with drug users in follow-up studies, says Nandakumar, thanks to the fact that it doesn’t require camera access or store any recordings, thus preserving privacy.

“The vast majority of people we ask want to use it. Do they engage in high-risk behavior? Yes. But they want to do it in a safe manner,” she says.

The challenge now will be encouraging take-up of the app among the population it’s targeting, says Traci Green, an associate professor at Brown University who specializes in opioid overdose prevention.

“You need to make sure the app is running on a phone that’s got enough battery and that people have access to data plans,” she says. “The question is: what access to tech do people need to make this great idea a reality?”