Space

In her light: space fiction

A short story about nanosatellites, love, and freedom

First NASA launched a few nanosatellites as experiments. Then a private space company sent up 300. Soon every government and major corporation had its own satellite network, and nearly a million nanosats were sprayed throughout low Earth orbit in twinkling constellations. No one wanted to talk about the sexual symbolism, because it was crude, which meant no one remembered that men left by themselves who are inflamed with passion can create quite a mess.

Someone needed to clean it up, and I was happy to sign up for the job. I had lingered on the B-list of human spaceflight for two decades after completing my service with the Royal Canadian Navy, supposedly because of my poor scores in leadership potential. This bothered me because not everyone needs to be a leader, to stick out their chest and tell others what to do. Thankfully, Bass-Xianhou Limited found my skills highly desirable—in particular, my work running a salvage operation for a decommissioned submarine in Baffin Bay. I joined a hundred other candidates from around the world to become an orbital ballistics control operator, or OBC—a sanitation worker of the stars.

My partner at Bass-Xianhou was Nanjira Yego, an aspiring astronaut from Mombasa with dyed blue braids who liked to wear heat-sensitive midriff tees and sparkling sneakers. During our training in French Guyana, Nanjira was a quiet, introspective loner who spent her free time jacked into StarWorlds, a massive online game. While I still harbored fantasies of finding the Right Stuff and becoming a Mars explorer, Nanjira visited imagined planets without any sense of embarrassment about our real-life jobs.

But in space, Nanjira transformed into a confident OBC operator who liked to question authority. She even sewed political patches onto her flight suit: free ubuntu! light brigade. quantum spin class. I found her brashness appealing, as if she could make up for my own conformity and meekness. She was a kind of anti-leader I wanted to follow, if that makes any sense. On the station I would try to work up the courage to invite her out, but we had little privacy under the banks of LED lights, so I would inevitably do nothing. Back on the surface, though, she would immediately immerse herself in StarWorlds, leaving me to bury my feelings for her through the intensive workouts they made us do to counter the effects of the time we spent weightless.

There was no press release or fanfare before our first mission. No endorsements of breakfast cereals or underwear. Bass-Xianhou booked us on an Ariane 6 out of French Guyana and hurled us into space along with three other sanitation teams. Once at the station, we docked for 24 hours to acclimatize, slept as much as we could, and then headed out to work.

Nanosats orbited closer to Earth than heavy satellites, which meant they offered lower latency and more stable communication. The latest ones adjusted dynamically to transmit data like a mesh network, but no common protocol had been developed between competing manufacturers, so sometimes they careened dangerously out of orbit. There were already millions of pieces of debris in orbit before the nanos, from discarded rocket stages to loose screws and lost tools, but the little satellites worsened the problem because many of them failed, adding to the detritus. The most legendary constellation belonged to Estée Lauder: a network of nearly a thousand gold-plated nanos that had immediately malfunctioned upon launch, and yet were rumored never to have fallen out of orbit. The talk amongst us OBCs was that if you caught them, you only had to extract the gold and you would retire in luxury.

Our job was to clean out the various giant nets that Bass-Xianhou had launched into different orbital planes. These nets had their own stabilizer jets that held them in orbits with known accumulations of debris. Like lobster fishermen, Nanjira and I would visit each “trap” on a prescribed route, spacewalking in tandem to the nets to extract the debris that had accumulated over weeks. Nanjira would bark instructions—“Up 20 degrees! Reverse, and four to the right!”—and I learned to listen to her. The general principle was to haul the debris back to the station, fish out the nanos, and repair the ones that still had some life in them, which reaped Bass-Xianhou extra revenue. The rest of the debris we would jettison to burn up in the atmosphere.

If it seems like a strange job, that’s because it was. Bass-Xianhou had never planned to launch humans into space, only automated drone sanitation systems. Their prototypes, however, weren’t nimble enough to pick the debris out of the nets. They had already secured several billion dollars’ worth of contracts, so they sent us OBCs as a stopgap. I didn’t gripe—the pay was good, and it beat salvaging submarines.

We catalogued each nanosat we collected. Many were from the so-called Third Tier of spacefaring nations—even minuscule São Tomé and Príncipe had managed to lob a few up. Some were labeled or had a scannable bar code, but other models—especially those that had been irradiated or damaged by a flare—did not show clear ownership. We were supposed to return unclaimed nanos to orbit, but sometimes, after taking a few plugs of whatever booze someone had smuggled aboard in French Guyana, we’d toss them out of the airlock to watch them burn up in the atmosphere. Nanjira liked to sprinkle different chemical compounds atop them like sesame seeds so that they would pop with bright colors.

It was juvenile, to be sure, but such moments helped us let off steam, because our work was dangerous. One time, a crew member returned from a spacewalk with his leg mashed by a chondrite meteoroid. His superkevlar suit had prevented it from being severed, but it flopped about like a tube of jelly. We had to put him into a partial coma and dispatch him back to the surface in an escape pod.

The station was skirting above the bleached white crust of the Great Barrier Reef one night when I noticed that Nanjira had disappeared into the toilet for longer than usual.

“You all right in there?” I shouted.

“Yes, why?”

“You’ve been in the head for a while.”

“You need to go?”

“No.”

“Okay, so wait your turn.”

I busied myself by sorting the nanosats we’d collected: repair, return, or discard. I logged seven Safaricoms and four Dancoms in the repair category, at about a $500 bonus for each; 30 miscellaneous (mostly Iroko) in the return pile; and then eight for the discard pile, which we would jettison.

After Nanjira returned from the bathroom, I re-counted our haul and found that we now had 12 in the repair bin.

“Where did you find that extra nano, Nanjira?”

“We got it outside.”

“I don’t remember grabbing it.”

“Leave me alone, Marcus.”

I decided not to press her. Instead, I examined the nano, made a few minor repairs, and relaunched it into orbit the next day. Still, I found it suspicious that Nanjira would keep secrets from me on the station. We could activate privacy screens that shielded out sound and light, but we knew each other intimately. After the gravity centrifuge stopped working one day, we had to race through the station to catch turds that had escaped from the toilet. When your fellow crew member’s poo gets on your face, there’s not much else you can be embarrassed about.

The next haul was a lucrative one. Nanjira and I maneuvered together, balletic in our coordination, to collect our haul from a net on an especially difficult orbital plane. Yet the moment we docked, she disappeared into the toilet and stayed there for 15 minutes. I barged in to find her dismantling a Dajiang MS142, a variant of a common Asian nanosat.

“Why are you doing that in here?”

“No cameras,” she said, pointing at the walls. It was true—the toilet was the one area of the station that even Bass-Xianhou did not observe. She inserted a tool that looked just like the one we used to plug in to nanos so the system could analyze them. Then she adjusted a piece inside the satellite, and screwed the plate shut.

“Will you tell me what you’re doing?”

She shook her head. “It’s better if you don’t know.”

Back on Earth, I grew nervous when the management at Bass-Xianhou called an emergency meeting, thinking that perhaps Nanjira’s tinkering in the toilet had been discovered. Instead, our route planner explained to us that an Israeli-French firm had cracked the so-called automation problem and was expected to launch its first products within a year—drone sanitation systems with no need for a human crew. To cut back on costs, Bass-Xianhou was reducing our bonus pay for fixing repairs. We would also be subjected to random audits.

“You’ve all signed noncompete clauses,” the vice-president of the company growled. “So don’t bother selling out to those copycats, or we’ll sue your ass.”

But on our very next route, once again I found Nanjira squirreled away in the toilet fixing a Dajiang.

“Aren’t you afraid of being caught, Nanjira?”

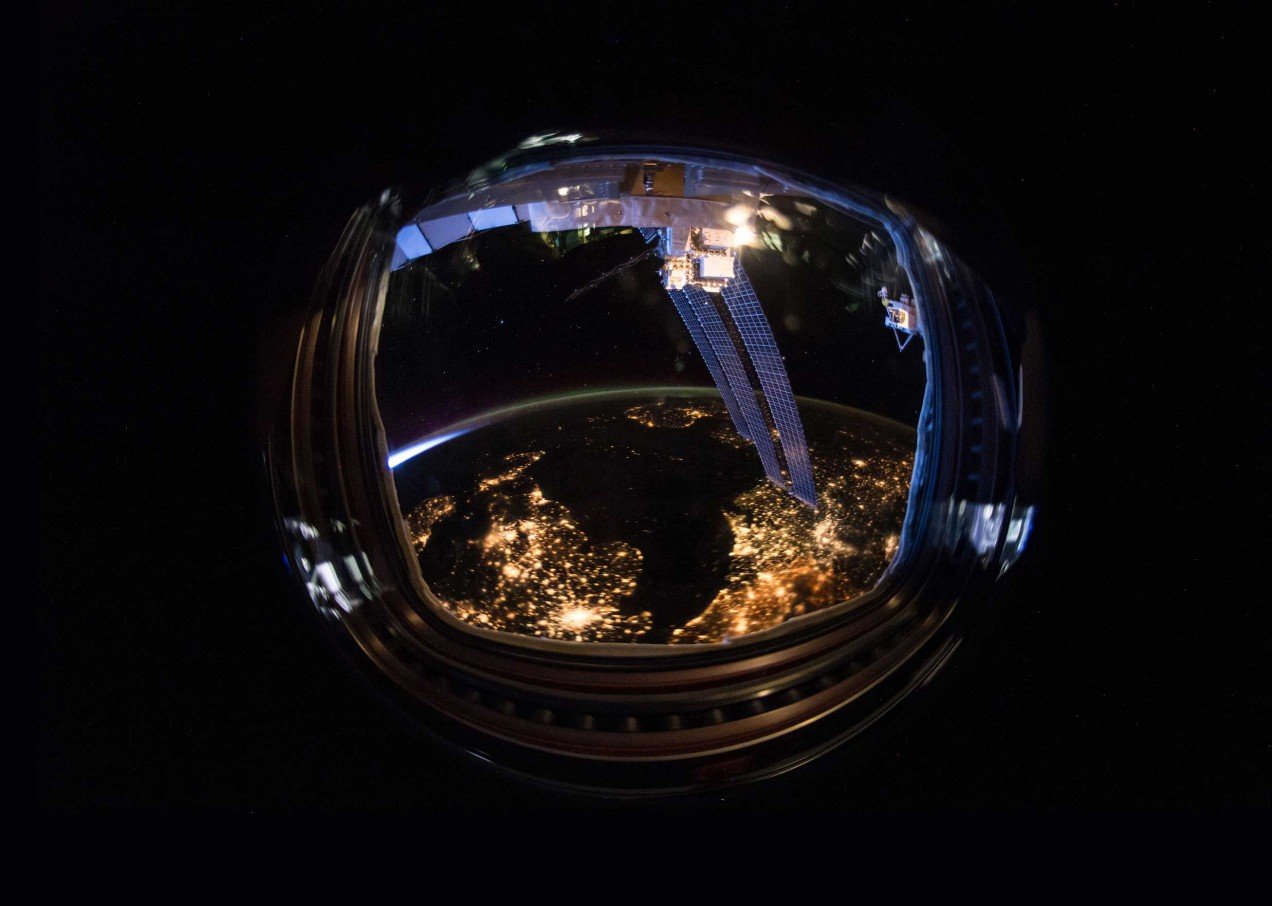

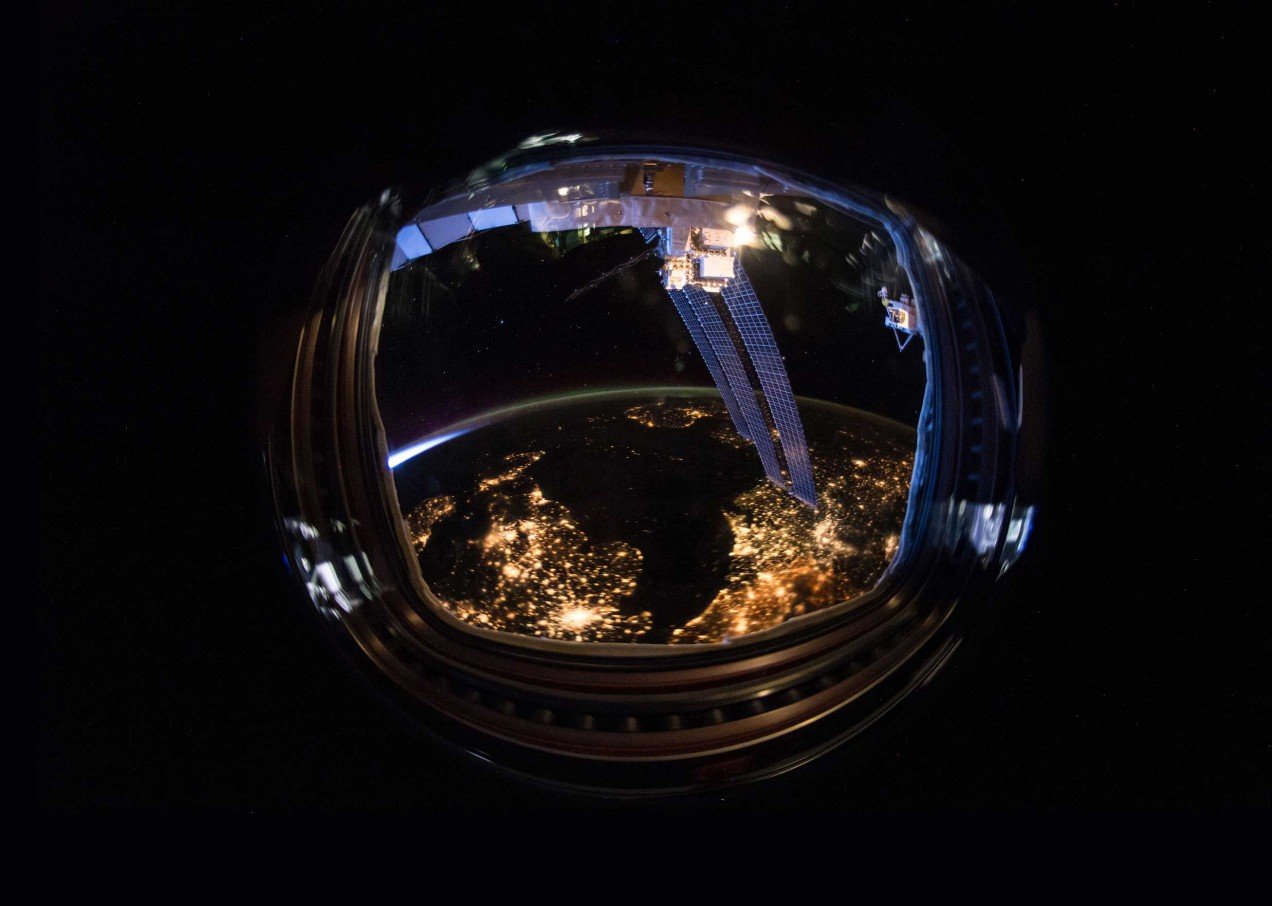

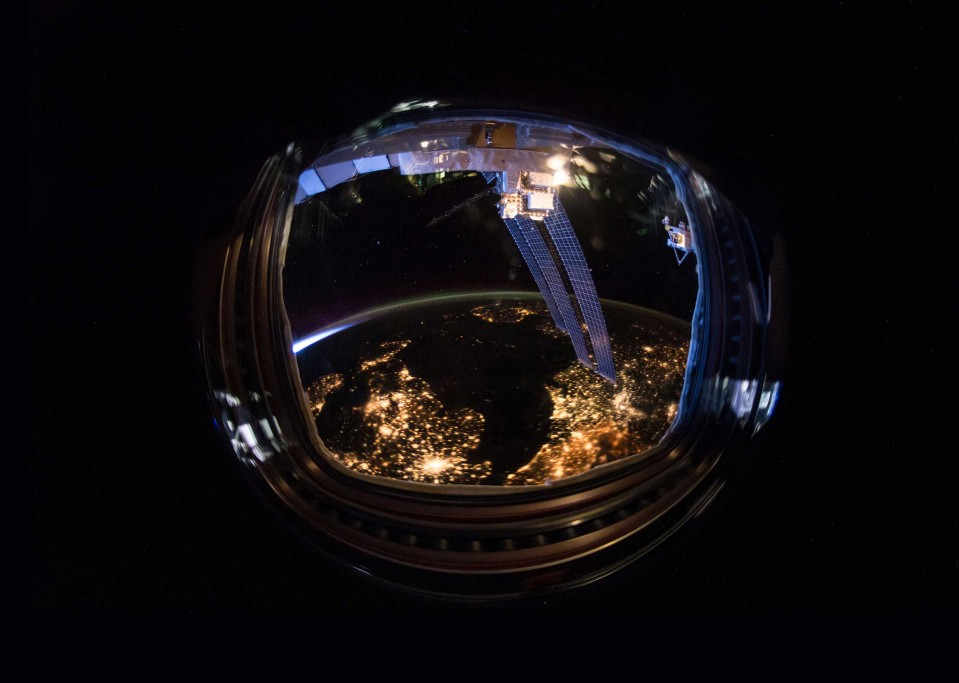

We watched the jagged Horn of Africa slide beneath us, pinpricks of light spread all over, with corridors of illumination linking the cities across the region. “There—what do you see, Marcus?”

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “I’m almost done.”

“Almost done with what? Can you at least tell me? We’ve worked together for nearly three years now, and for all I know we’re about to lose our jobs. What are you doing to those nanos? Spying for the copycats?”

“You really want to know?” Nanjira asked.

“Yes.”

“Follow me.”

We climbed some handholds to the small cafeteria, actually just a table folded into the wall, and she pointed through the large observation porthole. I could smell the geranium-scented wipes she used to mop her brow after we completed a route. We watched the jagged Horn of Africa slide beneath us, pinpricks of light spread all over, with corridors of illumination linking the cities across the region. “There—what do you see, Marcus?”

“Maglev lines.”

“You see the connections. Your eyes are drawn to the light. But what’s in the dark?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Desert. Mountains.”

“Many people,” Nanjira said, wistfully. “Many people live in that darkness.”

“That’s why we’re up here,” I said. “To service the nanos. To help those people stay connected.” This was our sacred responsibility, instilled in us by Bass-Xianhou on our first day.

But she had a determined look in her eye. “Connected to what? What are they connecting to?”

Related story

A Full Life

A science-fiction story about America in the age of climate change.

“To each other,” I blurted. “To information. To knowledge. Knowledge about their lives and how they can live them better. It’s why everyone has the right to a node now.”

She gave me a look that I wanted to interpret as fondness.

“The right to a node? Sure. A node that harvests their data, feeds them ads and propaganda, filters out what they aren’t supposed to see.” She swept her hand across the Earth beneath us. “Think of all this spectrum, Marcus. All of that light beaming information down to the planet from the nanos. All I’m doing is taking a little slice of that spectrum. A tiny, infinitesimal sliver that’s rarely used.”

“You’re talking about stealing.”

“I’m talking about untapped potential.”

“Our job is to maintain the network. You shouldn’t get your hands dirty in all this.”

“My hands are dirty?” she said, smiling. “Take a look at our catch next time and tell me if you really believe that.”

I did take a look the next time, and I didn’t see anything particularly strange about our catch. In fact, we had a bumper crop: nearly 100 nanos, with three dozen Standard Bank crypto-nanos in prime repair condition, and 12 Mo-Cola energy drink nanos that seemed serviceable. Nanjira did her thing and disappeared once again into the toilet after fishing a Dajiang from the spoils.

We were fortunate to have made that haul, because we soon received notice from Bass-Xianhou that our program was going to go through “slimming.” The French-Israeli competitor had underbid us on a major contract and our company was now planning to shift to servicing government--owned nanos, which were much less lucrative but would offer a stable source of income, according to our executives.

Strangely, Nanjira didn’t seem bothered by the news. In fact, she laughed more easily and joked with the other crew members without a care in the world. I wondered if she had taken too many stims, and whether there would be enough left over for me—we’d been working for nearly 72 hours straight.

“It’s finished,” she announced, happily.

“You mean you’re done with your thieving,” I goaded.

“Marcus, no one should own the light. The nodes are corrupted. Every single one is owned. We need a pure band, not an on-ramp to some bullshit data mining or shopping experience. It’s what we deserve.”

“That’s how the internet was in the beginning,” I said, “and it was polluted. That’s why we controlled it. Humanity wasn’t ready.”

“This is different, Marcus. We’re building it within—tunneling through the very heart of the beast. This spectrum will live in the center, hidden as if behind a cloud, and belong to anyone who can find it.”

Her passion for the cause made me want to kiss her, but she was looking at me as if I were a poor student who might one day, with a little extra effort, catch on.

We didn’t speak much before our next route, yet we behaved like total professionals as soon as we left the airlock. Nanjira barked instructions and I swiftly complied, even more eager to please her than before, as if I could reconcile our differences that way. We extracted over 50 nanosats from the net in record time. I managed to grab one in my glove. It was about five centimeters wide and coated in shimmering gold. It was clear its stabilizing propulsion system was still active, giving off light puffs of air like a perfume bottle. Only its uplink was switched off.

“Nanjira!” I shouted. “We found them!”

“What?”

“The Estée Lauder constellation! We hit pay dirt!”

“Are you sure—” she began, and then it sounded as if someone had punched her in the gut.

“Nanjira?”

I looked along the net. She had crumpled over in her propulsion chair and was trying to remove her boot, her fingers fluttering at the straps. Her chair suddenly began accelerating toward the net.

“Watch it, Nanjira! Shut off your jets!”

Except she kept on trying to unstrap her boot, as if it were the most important thing in the world.

“Home!” I shouted to the station. “Status on Nanjira.”

A voice crackled back. “Heart rate spiked. Air is intact.”

Her chair had now pushed into the center of the net, which was starting to coil and swoop down upon her like a giant wave. If she became entangled, it would be almost impossible to extract her.

“Marcus …” I heard her whisper.

“Roid shower!” home announced. “Escape protocol.”

“There’s something wrong with her.”

“Escape protocol!”

“I’m telling you she’s not responding!”

I could see the streaks in the corner of my vision, some of the meteoroids catching in the net, while the microscopic ones pushed right through it and flamed into the atmosphere. I launched myself toward my partner.

“Nanjira!” I yelled. “I’m coming!”

A roid slid past my visor as I unfastened her from her chair and clipped her to my own. Then my escape jets flung us away and back toward the station.

“We hit pay dirt, Nanjira,” I found myself saying over and over again. “Pay dirt.” But she only moaned. Back in the airlock, she slumped against a wall as I disrobed from my suit. Now I saw why she was trying to unstrap her boot—it was bulging as if it had filled up with water. But when I released the strap, blood gushed into the airlock.

“No!” I shouted. “No! No!”

The medic entered the airlock, unbolting Nanjira’s helmet, her blue-dyed braids drifting up around her head. Her eyes were open as if she were staring into a brilliant light. I began waving my hand in front of her face. “Nanjira! Wake up. Wake up!”

“Sensors 14 through 45 were triggered. Traumatic impact.”

“No!” I said. “It’s just blood. We can fix this. Snap out of it, Nanjira!”

“She’s dead, Marcus.”

Through the porthole, I saw the net filling up with meteoroids and starting to fall slowly, inexorably, toward the planet.

I found myself lingering in the living room of her family’s compound, trying to make sense of her journey from Kenya to the stars.

At her funeral in Mombasa, Nanjira’s family probed me with questions to determine if we had been lovers, as if such intimacy, even unsanctioned, would impart some dignity to her passing. I felt ashamed that I couldn’t even offer them that, when she herself had mustered the strength to utter my name in the midst of all that pain. I found myself lingering in the living room of her family’s compound, trying to make sense of her journey from Kenya to the stars. She was by no means poor, as I had stupidly assumed, and clearly came from a prosperous and loving family.

Her kid sister tugged at my arm and pulled me toward Nanjira’s bedroom. “Nanjira wanted you to see this,” she said.

Her sister had set up a node for me, and hooked me into the game. My entire field of vision was filled with ships: dreadnaughts, cruisers, fighters, battle destroyers, transports, ice tugs, seemingly every ship ever imagined or built in StarWorlds. In the vastness, a spinning wheel of white light opened and the ships began moving toward it. It looked like an event horizon with a beautiful corona. This was it, I understood. This was the spectrum Nanjira had sliced away from those nanos, her tunnel into a new, unfettered place where our words could mean what we wanted them to mean. One by one the ships began to approach the corona and disappear. I joined them, moving toward the light.

Deji Bryce Olukotun is the author of the novels After the Flare and Nigerians in Space. He works at the sound experience company Sonos.