Humans and Technology

“Old age” is made up—and this concept is hurting everyone

Products designed for older people reinforce a bogus image of them as passive and feeble.

Of all the wrenching changes humanity knows it will face in the next few decades—climate change, the rise of AI, the gene-editing revolution—none is nearly as predictable in its effects as global aging. Life expectancy in industrialized economies has gained more than 30 years since 1900, and for the first time in human history there are now more people over 65 than under 5—all thanks to a combination of increasing longevity, diminished fertility, and an aging Baby Boom cohort. We’ve watched these trends develop for generations; demographers can chart them decades in advance.

And yet we’re utterly unprepared for the consequences.

We are unprepared economically, socially, institutionally, and technologically. A wide swath of employers in the US—in both industry and government—are experiencing what has been called a retirement brain drain, as experienced workers depart crucial roles. At the same time, unemployed older workers struggle to find good jobs despite unemployment rates now at a 50-year nadir. Half of older longtime job holders, meanwhile, are pushed out of their jobs before they planned to retire. Half of Americans are financially unprepared for retirement—25% say they plan to never stop working—and state pension systems are hardly better off. Public transportation systems, to the limited extent they even exist outside of major cities, are unequal to the task of ferrying a large, older, non-driving population to where it needs to go. The US also faces a shortage of professional elder-care providers that only stands to worsen as demand increases, and in the meantime, “informal” elder care already extracts an annual economic toll of $522 billion per year in opportunity cost—mainly from women reducing their work hours, or leaving jobs altogether, to take care of aging parents.

And yet these problems might turn out to be surprisingly tractable. It’s strange, for instance, that employers are facing a retirement crisis at the same time that many older workers have to fight outright ageism to prove their value—sort of like a forest fire coexisting with a torrential downpour. For that matter, it’s strange that we, as a society, put obstacles in the way of older job seekers given that hiring them could help prevent programs like Social Security and Medicare from running out of money.

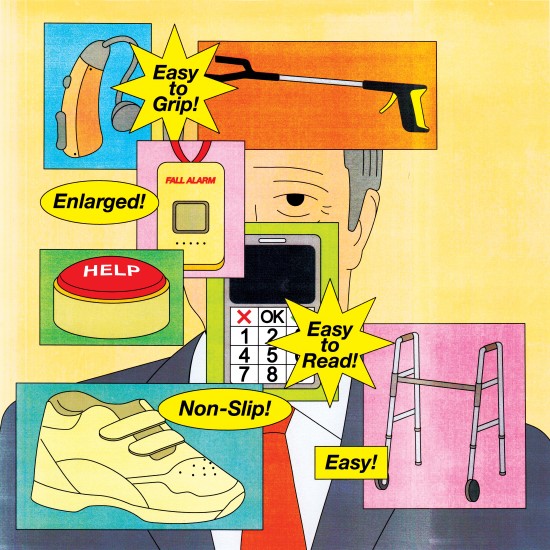

The MIT AgeLab, which I head, has homed in on one such paradox in particular: the profound mismatch between products built for older people and the products they actually want. To give just a few examples, only 20% of people who could benefit from hearing aids seek them out. Just 2% of those over 65 seek out personal emergency response technologies—the sorts of wearable devices that can call 911 with the push of a button—and many (perhaps even most) of those who do have them refuse to press the call button even after suffering a serious fall. History gives us many examples of such failed products, from age-friendly cars to blended foods to oversize cell phones.

In every example, product designers thought they understood the demands of the older market, but underestimated how older consumers would flee any product giving off a whiff of “oldness.” After all, there can be no doubt that personal emergency response pendants are for “old people,” and as Pew has reported, only 35% of people 75 or older consider themselves “old.”

Asking young designers to merely step into the shoes of older consumers (and we at the MIT AgeLab have literally developed a physiological aging simulation suit for that purpose) is a good start, but it may not be enough to give them true insight into the desires of older consumers.

There’s an expectations gap between what older consumers want from a product and what most of these products deliver, and it’s no frivolous matter. If you need a hearing aid but no one can make one that you think is worth buying, that will have serious ramifications for your quality of life, and may lead to social isolation and physical danger down the road.

But the expectations gap is also—here’s that word again—strange. Why do products built for older people so often seem so uninspiring—big, beige, and boring? It’s not that older people don’t have money. The 50-plus population controls 83% of household wealth in the US and spent more in 2015 than those younger than 50: nearly $8 trillion of economic activity, if you include downstream effects. Granted, that wealth is unequally distributed, but if better products existed, you’d expect to see them snapped up by the people with more money, and that hasn’t happened (with a handful of very recent exceptions I’ll discuss).

And don’t try to tell me the real issue is that older people aren’t tech savvy. Maybe that stereotype once contained a grain of truth—in 2000, just 14% of 65-plus America used the internet—but it’s no longer the case. Today, 73% of the 65-plus population is online, and half own smartphones.

The expectations gap, then, is the sort of vacuum one would expect nature not to tolerate. If you believe that markets, given enough demand, tend to solve problems sooner or later, the gap’s persistence is uncanny: like a Volkswagen-size boulder hovering six inches off the ground.

Don’t worry; there is a natural explanation—and it holds clues for how we can turn many paradoxical problems of global aging into opportunities.

The root cause of all this daylight—between products and consumer expectations, between employer and older worker, between what 75-year-olds think of as “old” and their self-conception—is disarmingly simple. “Old age,” as we know it, is made up.

To be sure, a full Whitman’s Sampler of unpleasant biological contingencies can arrive with age, and death ultimately comes for us all. But the difference between those hard truths and the dominant narrative of old age that we’ve inherited is big enough and persistent enough to account for the expectations gap—and then some.

Two hundred years ago, no one thought of “the aged” or “the old” as a population-size problem to be solved. But that changed thanks to a confluence of since-debunked science and frenzied institution-building. In the first half of the 19th century, doctors, especially in the US and UK, believed that biological old age occurred when the body ran out of a substance known as “vital energy,” which, like energy in a battery, was consumed over the course of a lifetime of physical activity, never to be replenished. When patients began to display key signs of old age (white hair, menopause), the only medically sound response was to insist they cut back on all activities. “If death resulted from an exhausted supply of energy, then the goal was to retain it at all cost,” historian Carole Haber wrote in her 1994 book Old Age and the Search for Security, “by eating the correct foods, wearing the proper clothes, and performing (or refraining from) certain activities.” Sex and manual labor were both considered to be especially draining.

By the 1860s, modern notions of pathology had begun to replace vital energy in continental Europe, and they eventually found their way to the US and UK. In the meantime, however, social and economic developments were taking place that would preserve as though in amber the conception of old age as a period of passive rest.

In the increasingly mechanized workplace, efficiency was the new watchword, and by the turn of the century, experts were clambering out of the drywall in offices and factories everywhere, offering to wring extra productivity out of workers. The older worker, low on vital energy, was an easy target. As one efficiency expert, Harrington Emerson, argued in 1909, when a company retired its oldest workers, it produced “a desirable wriggle of life all the way down the line.” Private pensions—which were first introduced by the American Express company in 1875 and exploded in the decades that followed—were one natural response. They were issued in some cases out of genuine humanitarian concern for unwillingly retired employees, but also because they gave managers the moral cover they needed to fire workers merely for the crime of superannuation.

By the 1910s, it was conventional wisdom that oldness constituted a problem worthy of action on a mass scale. Between 1909 and 1915, the country saw its first federal--level pension bill, state-level universal pension, and public commission on aging, as well as a major survey investigating the economic condition of older adults. In medicine, the term “geriatrics” was coined in 1909; by 1914, the first textbook on that specialty was published. Perhaps the best representation of the tenor of the time was a 1911 film by the important (and notoriously racist) filmmaker D. W. Griffith, which told the story of an aging carpenter falling into penury after losing his job to a younger man. Its title was What Shall We Do With Our Old?

By the start of World War I, the first half of our modern narrative of old age was written: older people constituted a population in dire need of assistance. It wasn’t until after World War II that the second half arrived in the form of the “golden years,” a stroke of marketing genius by Del Webb, developer of the Arizona retirement mecca Sun City. The golden years positioned retirement not just as something bad your boss did to you, but rather as a period of reward for a lifetime of hard work. As retirement became synonymous with leisure, the full 20th-century conception of oldness took form: if you weren’t the kind of older person who was needy—for money, for help with everyday tasks, for medical attention—then you must be the kind who was greedy: for easy living and consumerist luxuries.

With both wants and needs spoken for, this Janus-faced picture gave the impression of comprehensiveness, but in fact it pigeonholed older people. To be old meant to be always a taker, never a giver; always an economic consumer, never a producer.

One of the more conspicuous ways the constructed narrative of old age exerts itself today is in products built for older people, which tend to fall to either side of the needy/greedy dialectic: walkers, medications, and pill-reminder apps on one hand, and cruise ships, booze, and golfing green fees on the other.

There’s more to life than the stuff you buy, of course. And yet, there is good reason to believe that the key to a better, longer, more sustainable old age may just lie in better products, especially if we define “product” broadly: as everything a society builds for people, from electronic doodads to foods to transportation infrastructure.

Consider the text message. Originally billed as the province of gossiping teenagers, it’s been a godsend for deaf people. Transcendent design, as we at the AgeLab call such developments, offers a solution that’s larger than the baseline needs of older people, but still includes their needs. The electric garage-door opener is another example: originally designed as a mechanical aid for those incapable of lifting heavy wooden doors, it offered convenience too attractive to ignore, and found its way into general use.

The nascent field of “hearables”—earbuds capable of such tasks as real-time translation and augmenting certain environmental sounds—may finally destigmatize assistive hearing devices. Sharing-economy services, meanwhile, offer services à la carte that were previously obtainable only as a bundle in assisted-living settings. When you can summon grocery deliveries, help around the house, and rides on demand from your phone, you might even delay a move to a more institutional setting—especially since it might save you a lot of money along the way. Some 87% of people over 65 say they’d prefer to “age in place” in their own homes.

But for the purposes of rewriting narratives, even more important than what products do is what they say. I could write a hundred op-eds extolling the virtues of older people, but any positive effect they have on public perception would be far outweighed by a single infantilizing product on store shelves. When a company builds something that treats older people as a problem to be solved, everyone gets the message immediately, without even having to think about it.

Products have perpetuated the reductive narrative of old age in a vicious cycle that has lasted decades. It works something like this: The entire product economy surrounding old age reinforces an image in the public’s mind of old people as passive consumers. Then, when an older adult applies for a job, she must fight this ambient sense—call it ageism if you like—that she, a consumer by nature, doesn’t belong in a production role. As a result, her hard-won experiences rarely find their way into design decisions for new, cutting-edge products—especially the high-tech ones likely to shape how we’ll live tomorrow. And so, without such insight to guide them, the few designers who deign to innovate for older people turn, without realizing it, to the ambient narrative, ultimately churning out the same old reductive products. And so the cycle perpetuates itself.

I’m hardly the first academic to note that the free market can cast what amounts to a distorting field over reality, but in this rare case it may be possible to harness the energy of that market and aim it squarely at our old-age myths. After all, the expectations gap wants to be closed—that hovering boulder wants to crash to the ground—for the simple reason that companies stand to make more money by better serving the truly massive older market.

Such a development won’t solve every problem associated with aging, of course. Income inequality and racial inequities both intersect with aging in troubling ways. Wealthier and whiter Americans are more likely to be better financially prepared for retirement, as well as to be healthier and live longer. Fixing how we think about older people isn’t going to solve those inequities, but it may at least make the premature firing of older people less common, and help them find better-paying jobs.

It works something like this: The entire product economy surrounding old age reinforces an image in the public’s mind of old people as passive consumers. Then, when an older adult applies for a job, she must fight this ambient sense—call it ageism if you like—that she, a consumer by nature, doesn’t belong in a production role.

It also won’t solve the epidemic of suicides, or “deaths of despair,” plaguing middle-aged Americans. But on the other hand, redefining “old age” from a black hole of passivity to a period marked by activity, agency, and even renewal surely couldn’t hurt the view from middle age. When you’re talking about changing the very meaning of the final third (or more) of adult life, it’s impossible to predict all the effects that will spider-web out through earlier stages. Perhaps the promise of a brighter future won’t matter much to people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s—but it certainly won’t make matters worse. In fact, I wonder if a new, more realistic image of old age might motivate younger and midcareer workers to save more for the future, and lead them to demand better retirement benefits from employers. For the first time, they may find themselves saving not for some hypothetical older person, but rather for a better version of themselves.

Technologists, particularly those who make consumer products, will have a strong influence over how we’ll live tomorrow. By treating older adults not as an ancillary market but as a core constituency, the tech sector can do much of the work required to redefine old age. But tech workplaces also skew infamously young. Asking young designers to merely step into the shoes of older consumers (and we at the MIT AgeLab have literally developed a physiological aging simulation suit for that purpose) is a good start, but it is not enough to give them true insight into the desires of older consumers. Luckily there’s a simpler route: hire older workers.

In fact, what’s true in tech goes for workplaces writ large. The next time you’re hiring and an older worker’s résumé crosses your desk, give it a serious look. After all, someday you’ll be older too. So strike a blow for your future self.

Global aging may be inevitable, but old age, as we know it, is not. It’s something we’ve made up. Now it’s up to us to remake it.

Joseph F. Coughlin (@josephcoughlin on Twitter) is the director of the MIT AgeLab and author of The Longevity Economy.