Back in March, Vice President Mike Pence made a surprise announcement: the government was directing NASA to put astronauts back on the moon within five years. This 2024 deadline was always going to be difficult to hit, but it has since morphed into an extremely unlikely scenario for the agency and its partners.

At the National Space Council meeting last week, Pence and NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine went out of their way to emphasize how much support the agency's new lunar program, Artemis, has among the public and private sectors. “Our moon-to-Mars mission is on track, and America is leading in human space exploration again,” Pence told the audience at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center.

What Pence didn’t mention was the serious issues that plague the program and its 2024 hopes. Some of these obstacles are recent, while others have persisted since Donald Trump took office. Here are the five biggest obstacles that make a 2024 moon landing by American astronauts unlikely.

Money woes

Artemis’s biggest problem is money—or a lack of it. The Trump administration began the year requesting $22.6 billion for NASA’s 2020 budget, which now includes an additional $1.6 billion request made just before this summer. Many experts believe that this budget, even with the extra bump, isn’t enough to accelerate Artemis's timetable. “There’s a remarkable gap between the rhetoric surrounding Artemis and the reality of the current situation,” says John Logsdon, a space policy expert based at George Washington University.

Casey Dreier at the Planetary Society predicts that the agency will need an annual $4 to $5 billion increase at minimum for the next several years in order to successfully hit a 2024 deadline. The other options are to slash other NASA programs (the Earth Science programs are constantly under threat) and redirect the money toward Artemis-centric projects, or get the money from other federal programs like Pell Grant reserves that help low-income students afford college.

Congress loves NASA, but it's lukewarm on Artemis. The head of the subcommittee responsible for NASA funding in the Democratic-led House is already skeptical of the mission and its goals. The good news for Artemis is that Congress is unlikely to cannibalize other NASA programs or other federal programs. If the White House asked for more money, Congress would probably acquiesce.

Whiplash expectations about SLS and Orion

Budget issues have also created uncertainty around the two most important elements of NASA’s deep space ambitions: the Orion crew capsule, and the Space Launch System that is poised to be the most powerful rocket in history. When SLS was first announced in 2010, there were expectations the first launch would occur in 2017, sending Orion on an uncrewed journey around the moon and back.

Development delays hit both pieces, and the first Orion mission (now called Artemis 1) will likely now be in 2021. Those delays encouraged NASA to contemplate cutting the SLS budget and turn to a commercial company like SpaceX or Blue Origin to supply a rocket for Artemis 1—before it then reversed course and reiterated its commitment to SLS.

As a result, NASA has faced endless criticism over how much wasted spending has gone into SLS, especially when cheaper launch systems have started to take off. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have shown that even heavy lift rockets can be reusable, helping to reduce launch costs. SLS would not be reusable, and launch cost estimates range from $1.5 billion to $5 billion per launch. By comparison, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch costs around $90 million, and a trip to the moon theoretically should be only slightly more expensive than that. While NASA seems ready to ride SLS out to completion, Pence has previously suggested that the White House will turn to a commercial partner if NASA's own technology cannot meet its goals.

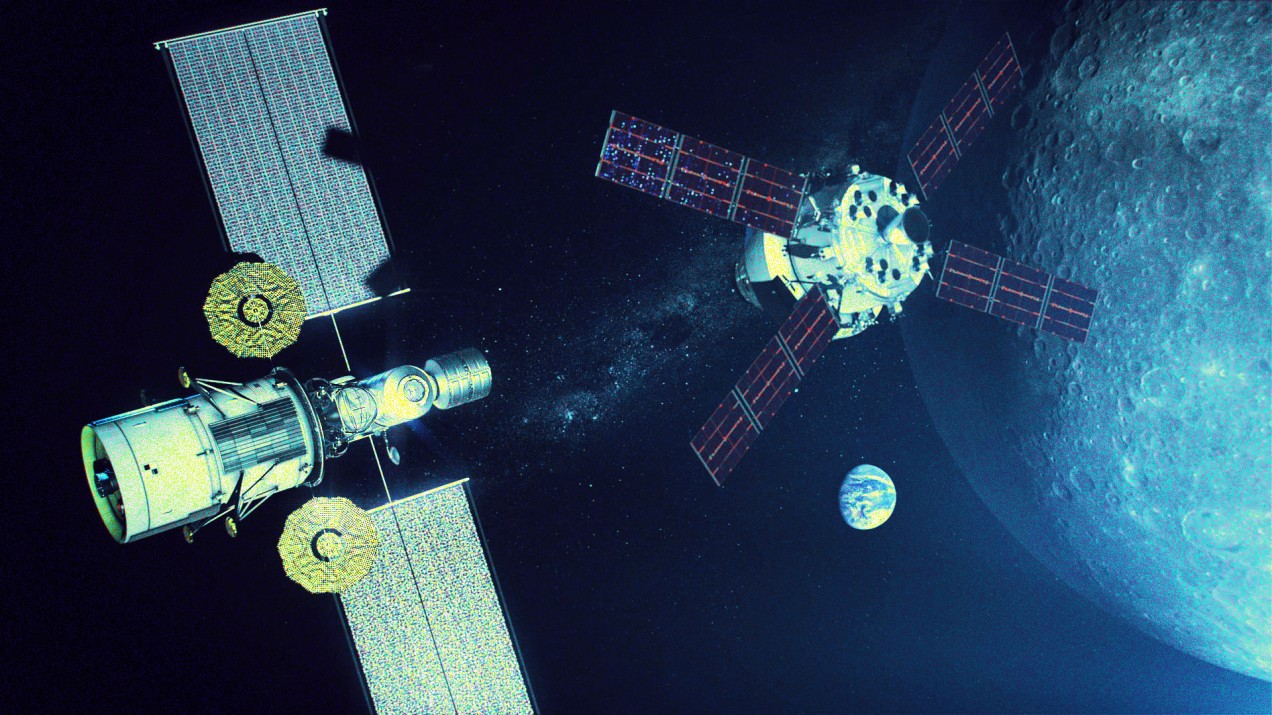

We've barely started on Gateway and a lunar lander

A key part of the Artemis program is a new lunar orbital space station called Gateway. Astronauts would orbit the moon in this space station before descending to the surface. In theory, Gateway could also be used to venture farther out to destinations like Mars. The first contract to build Gateway’s habitation module was awarded in May, but don’t expect it to be a real working space station anytime soon. At best, by 2024, it will be only a bare-bones station from which astronauts could take a lander module down to the lunar surface. Many have called into question how useful Gateway will be—former NASA administrator Michael Griffin and Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin are two of the biggest names opposed to it, claiming it’s an unnecessary distraction slowing us down from getting to the moon and Mars quickly.

Then there’s the fact that NASA has no real plan for building and testing a lunar lander. The agency is turning to the commercial industry for one, which makes sense in this case. Blue Origin, for instance, has already unveiled a design for a lunar lander called Blue Moon, and hopes that NASA decides to use it to send astronauts back to the moon in 2024. But the commercial industry doesn’t have the greatest track record for building and testing new spaceflight architecture. Asking a private company to build and test a lunar lander that needs to safely ferry astronauts in less than five years is a big ask.

Leadership worries during a period of change

Jim Bridenstine, a former Republican congressman, was confirmed as NASA chief last year in an extremely partisan vote, sowing fears that the agency was heading into unstable times. Bridenstine recently removed Bill Gerstenmaier as associate administrator for NASA's Human Exploration and Operations (a role he held since 2011). Gerstenmaier had been involved in the space shuttle program and the construction of the International Space Station, and oversaw the Commercial Crew Program and the Obama administration’s pivot to Mars before the Trump administration decided to go back to the moon again instead. His removal from leading Artemis was a shock, and Bridenstine has not yet named a replacement.

Gerstenmaier is not the only big name to leave NASA recently. Mark Sirangelo, an aerospace industry bigwig who joined NASA this year as an advisor on Artemis planning, was expected to become associate administrator of a new “moon to Mars mission directorate” that would have been explicitly focused on deep space missions, separate from low Earth orbit exploration. Congress rejected the idea, and Sirangelo left NASA soon after. With both Gerstenmaier and Sirangelo gone, it’s really unclear who exactly is in charge of Artemis.

“A leader is clearly needed—there needs to be a focal point to come in and take over,” says Logsdon. He believes the current upheaval is a symptom of NASA’s struggle to transition out of an Apollo-era approach to space, where the agency essentially built an American space-industrial complex, and into a “distributed system between government and private sector activities focused on achieving a common goal.” So far, we haven’t seen anyone able to make such a transition go smoothly.

What exactly is supposed to happen during a 2024 mission?

Much of the frustration directed toward a 2024 mission is simply because we don’t really know what the mission is for. What we know right now is that the mission “will look a hell of a lot like Apollo,” says Logsdon. At least two people are going to the surface (and at least one will be a woman) for a short period of time to do some exploration at the South Pole, where there is likely a huge cache of water ice. “Its main objective is to happen,” says Logsdon.

But we’re told we’re going to the moon to stay, as a prelude to going to Mars. How 2024 fits into this vision is still unclear. What kind of infrastructure are we establishing before landing? What tasks will astronauts complete during this mission? How long are they staying? How is a mission like this going to help us inaugurate a permanent presence on the moon? Are we laying down the first bricks of a lunar colony? What does the next Artemis mission after this one look like? So far there are no answers to any of these questions.