Rewriting Life

A Better Personal Health Record?

In the wake of Google Health’s collapse, one company hopes to promote personal health tracking through employers.

When Google recently announced it would discontinue Google Health at the end of this year, it left the fate of personal health records (PHRs) hanging. Unlike medical records kept by health-care providers, Google Health offered a single place where people could store, analyze, and share their personal health information. But it was hampered by a fragmented health system that made it difficult to collect medical information, and it relied on the initiative of consumers to gather their own data.

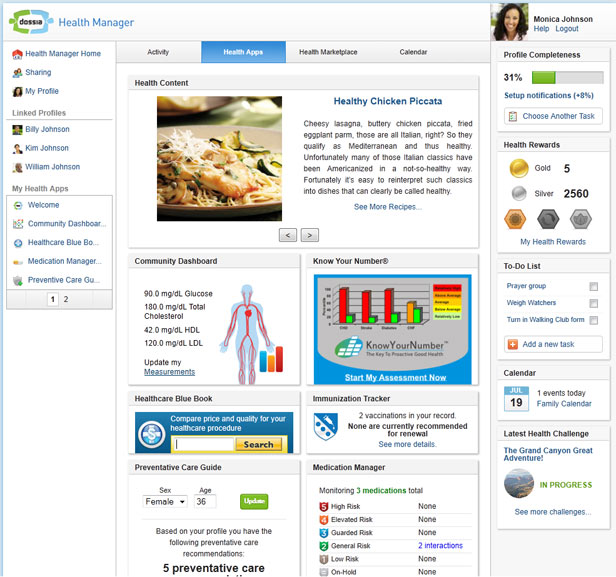

Not everyone is discouraged by Google Health’s demise. Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Dossia, a PHR provider that began as a nonprofit consortium of large employers, recently announced the launch of Dossia Health Manager, which will expand the company’s current PHR platform with a range of new features.

Unlike Google Health and similar services, Dossia’s system is linked to employer-sponsored health plans—its largest user is currently Walmart. Employers are interested in personal health records as a way to encourage healthy behavior—and thus cut down on the money they spend on insurance premiums. Dossia’s system can track subscribers’ health status and tie that information to incentives or rewards. For instance, it could determine whether people with high blood pressure are measuring and controlling their blood pressure and refilling their prescriptions. Dossia keeps employees’ private information secure from employers by using security technology similar to the kind used by the financial industry.

Dossia CEO Michael Critelli thinks Google Health’s fatal error was to require consumers to input their own information or request it from a doctor’s office. “Consumers are not going to go to the trouble of assembling their health information,” he says. Dossia’s PHR system uses the leverage of large employers to request insurance, pharmacy, dental, and physician records from multiple sources. Critelli says Dossia is subject to more regulation than Google Health because it accesses health information directly. But he says it’s worth it to take the burden off the consumer.

“The goal of Dossia is to merge clinical and nonclinical records,” says Critelli. It can hold records of lab test results and prescriptions from a doctor’s office, insurance information, and personal data from pedometers or health-monitoring devices. The expanded platform also provides a price comparison tool for people shopping for health services. It adds an option for a caregiver to take charge of the information of a family member.

But assembling information quickly and efficiently is no easy task. Critelli admits it’s Dossia’s greatest challenge. Legislation has given patients the right to control their own health information, but it doesn’t require that health plans, clinics, and hospitals provide that information quickly and automatically at a patient’s request, and many are reluctant to do so.

John Halamka, chief information officer of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, says that while it’s important to aggregate information, it’s even more critical to have information that’s integrated with a doctor’s office. So far, electronic health records have seen the most growth in “tethered” systems, which are connected to the clinician’s office. “My sense is that tethered PHRs are growing much faster than untethered PHRs because patients find value in clinical office integration more than consolidation of their records in one place,” he says.

Dossia’s system offers consumers some of the advantages of untethered records—they are portable from doctor to doctor, and include data from different sources—as well as the benefits of tethered records, because the data is gathered directly from physicians.