Sustainable Energy

Underwater Microscope Uncovers the Secret Lives of Coral Reefs in Danger

A new device that peers at corals in their natural habitat could help us understand how the world’s reefs respond to climate change.

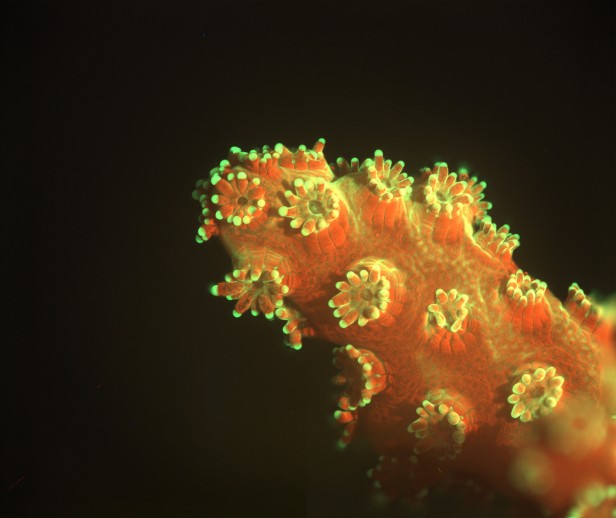

We are getting a new look at some of the ocean’s smallest creatures. Researchers have built a microscope that can be used up to 100 meters underwater to peer into the secret lives of coral, the tiny invertebrates whose skeletal superstructures make up the foundation of life in the seas.

The Benthic Underwater Microscope, developed by Andrew Mullen and colleagues at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, can do what no microscope has done before: record the activities of tiny marine organisms, some just a few microns across, in their natural habitat.

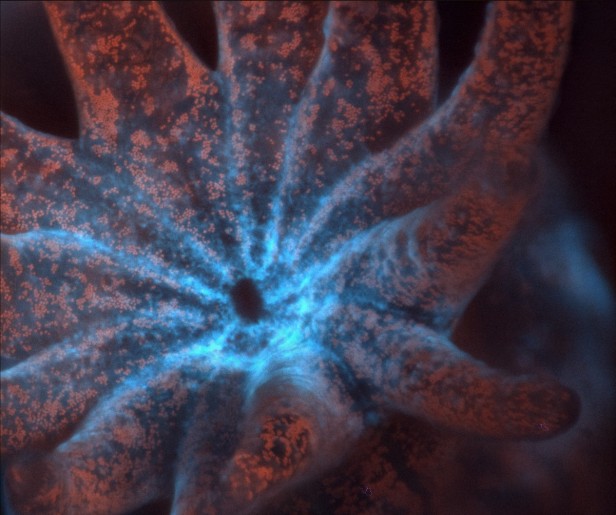

A paper released today in Nature Communications shows off some applications of the technology in coral reef ecosystems. Outfitted with a flexible lens that is similar to the lens in our eyes, the microscope can rapidly bring subjects at different distances into focus. It shines focused LEDs on its subject, allowing an onboard camera to take quick exposures and capture organisms as they move. A dive computer connected to the microscope allows the diver to control the whole setup, or it can be set to run on its own for extended periods.

Life in the world’s oceans depends on coral reefs. Though they cover less than 2 percent of the ocean floor, they support 25 percent of all marine species. But the reefs are in trouble. As climate change raises ocean temperatures, coral bleaching events like the one that devastated Australia’s Great Barrier Reef this year are becoming more common. Such events occur when coral colonies weaken from stress. Reefs can survive some bleaching, but repeated or prolonged events can lead to algae invading the reef and killing it off.

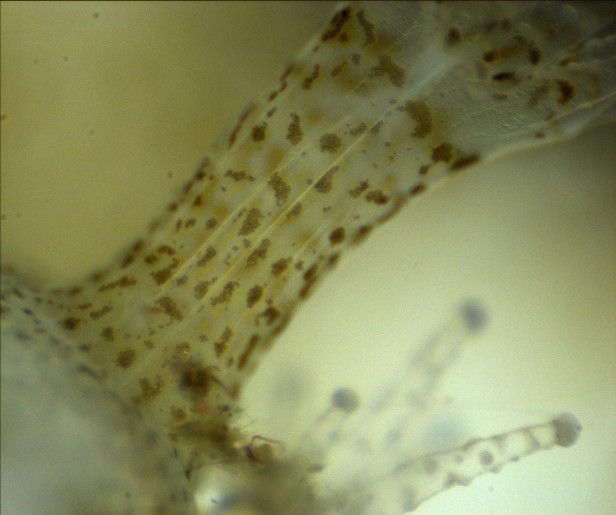

Mullen and his team recently used their microscope to document the ongoing battle between corals and algae in Maui, Hawaii, the site of a large coral bleaching event in 2015. The microscope’s fine-scale resolution allowed the team to observe key aspects of how this battle is going down: for example, the team learned that algae gain a foothold in bleached coral by initially intruding only on certain parts of it.

As the research continues, the team hopes that by watching the dramas of life and death play out on a tiny scale, they may one day find a way to turn their insights into a big help for a fragile part of the ocean ecosystem.