Biotechnology / CRISPR

CRISPR could help us cure sickle-cell disease. But patients are wary.

How accessible would a cure be to the people who need it?

A gene-editing technique that has shown promise as a potential cure for sickle-cell disease is now being tested in humans. But if it works, will the people who need it even be able to get it? Now that a cure may be in sight, this is an urgent question, says Vence Bonham, a senior advisor to the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute.

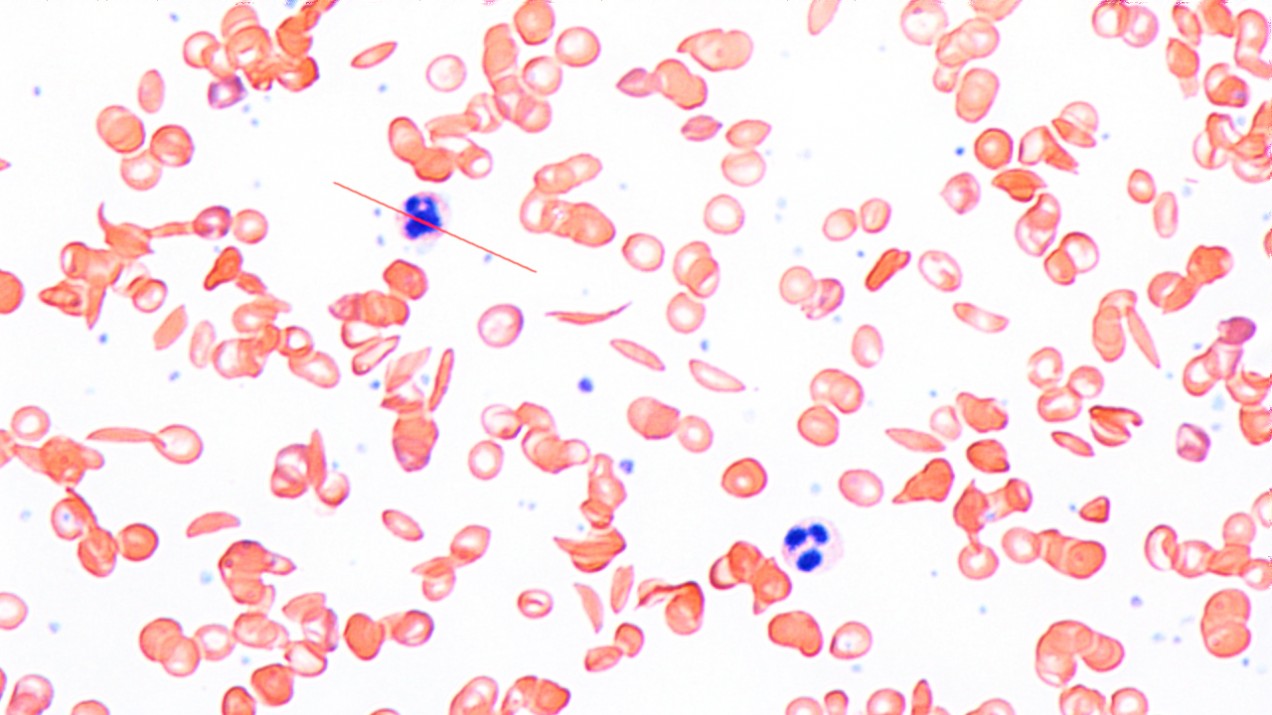

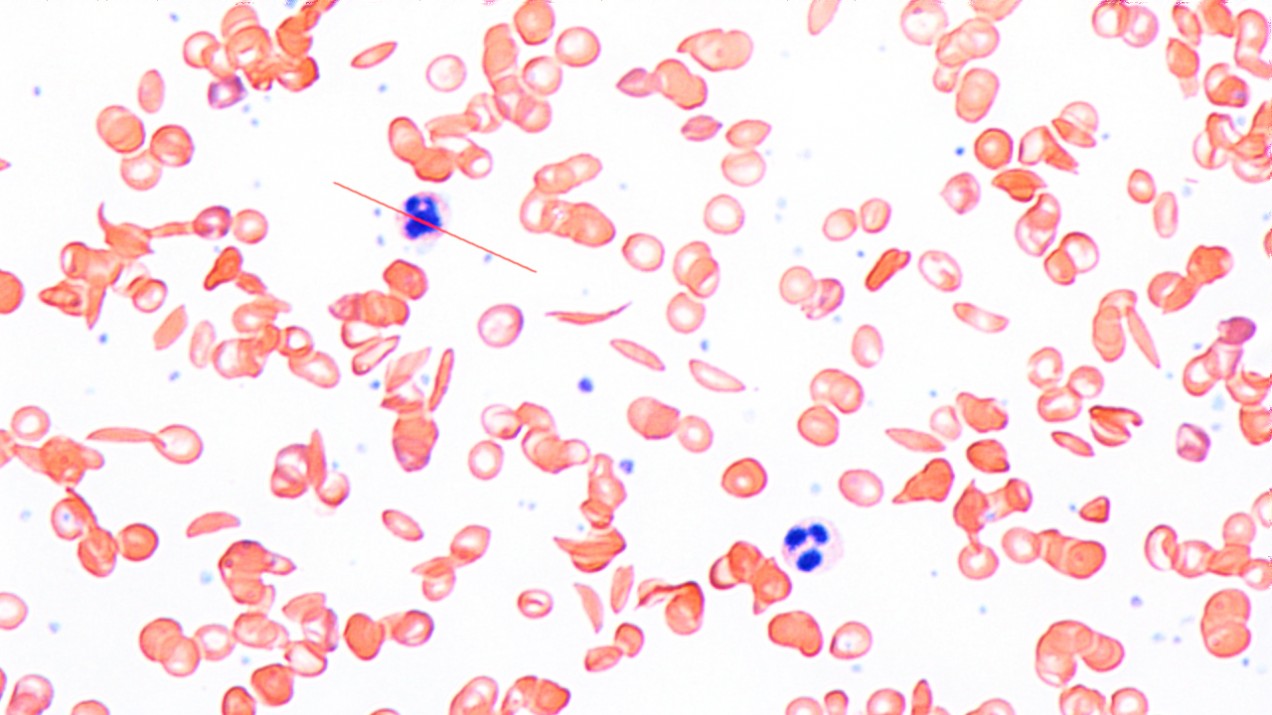

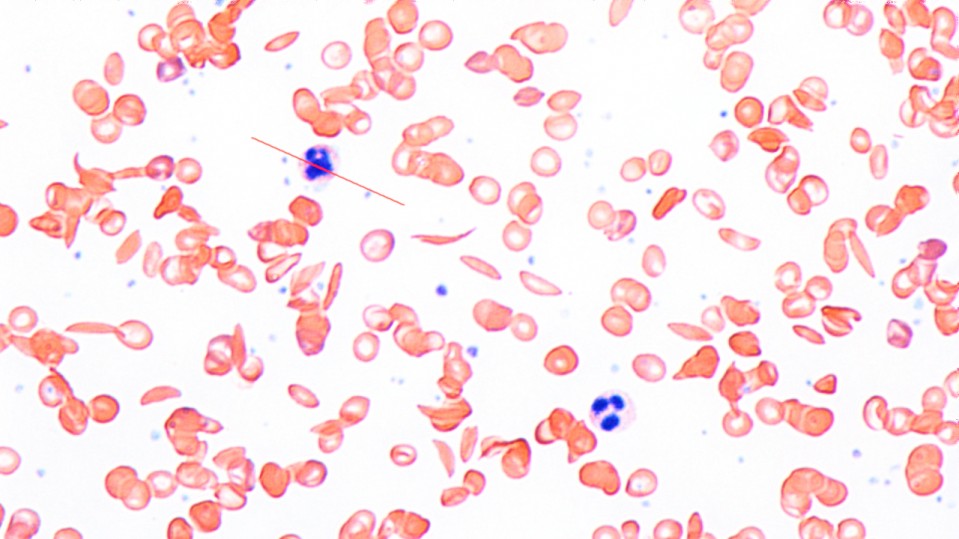

Sickle-cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder that affects millions of people in the world. It causes the production of abnormal red blood cells and can lead to intense pain, strokes, and organ and tissue damage.

From a scientific perspective, “it’s an exciting time” for people who suffer from the disease, Bonham said today at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference. Researchers are testing a technique that uses the precise gene-editing tool CRISPR to modify a single gene associated with the disease.

But from a sociological standpoint, argued Bonham, the work is just beginning. SCD is more common in certain ethnic groups, particularly people of African descent. And while there are around 100,000 people with the disease in the US, the vast majority live in sub-Saharan Africa and India, Bonham said.

He and colleagues recently conducted a study intended to explore the “attitudes and beliefs” toward the promising technique held among people with SCD, their family members, and their physicians. Many of the people Bonham and his colleagues spoke with expressed skepticism that a potential CRISPR-based cure would be affordable and accessible to those who need it. Although they did find “renewed hope,” they also observed “cautionary, apprehensive undertones to this hope,” which they concluded stem in part from decades of “medical disenfranchisement of the SCD community.”

According to one physician interviewed for the study, there is a danger that other rare diseases that tend to affect people “with more resources” might get more attention and, potentially, funding. As a result, there is a concern that the SCD population “could get left in the dust.” This population is already skeptical, since “they have been left in the dust with so many other things,” the physician added.

Besides a cure itself, we also need better and cheaper ways to “expand the benefits of this new technology,” Bonham said. “The potential is great, but we must ask the question: Who will benefit?”