Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz were awarded one half of this year’s Nobel Prize in physics today for their discovery of the first planet outside our solar system orbiting a sun-like star, which kicked off the dawn of exoplanet science in astronomy.

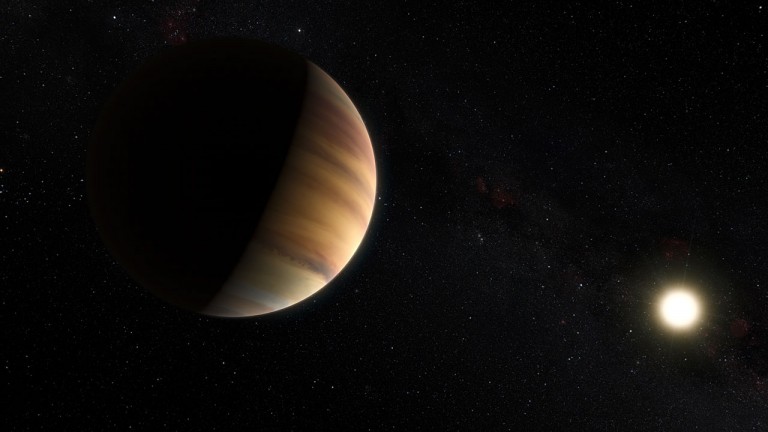

The history: In 1995, Mayor and Queloz identified a planet orbiting the sun-like star 51 Pegasi, over 50 light-years away in the constellation Pegasus. The pair used a spectroscope to detect tiny wobbles in the light emitted by the host star. These changes turned out to be induced by the gravitational effects of a large, hot, gaseous exoplanet orbiting the star 4.3 million miles away. That exoplanet, later named 51 Pegasi b, was confirmed a week later by another team using the Lick Observatory in California.

Although the first exoplanet detection was made in 1992 (with the discovery of a pair of planets orbiting a pulsar 2,300 light-years away), 51 Pegasi b was the first exoplanet to be found orbiting a sun-like star.

Just the tip of the iceberg: Since then, astronomers have discovered more than 4,000 exoplanets across the galaxy, spanning a huge range of types and sizes. We now believe most stars are probably orbited by planets––a radical shift from the conventional thought of most of the 20th century. Many of these discoveries have teased hopes of finding another world that’s habitable to life.

The other half: Canadian scientist James Peebles won the other share of this year’s Nobel Prize in physics for his work in studying the faint afterglow of radiation left over from the Big Bang, which created a framework for modern cosmology. Peebles’s theories eventually led to the characterization of dark matter and dark energy, and to the realization that only 5% of the universe is made of ordinary matter.