Rewriting Life

This Gadget Has a Real Working Menstrual Cycle

The latest organ-on-a-chip can release an egg in 28 days.

A virtual representation of a human being is known as an avatar. But what about a biological representation of the female reproductive organs?

That would be “Evatar.”

We’ve seen other organs-on-chips before, acting like little lungs or livers. Now Evatar, say its creators, is the first laboratory gadget able to copy a 28-day menstrual cycle, during which an egg matures and gets released.

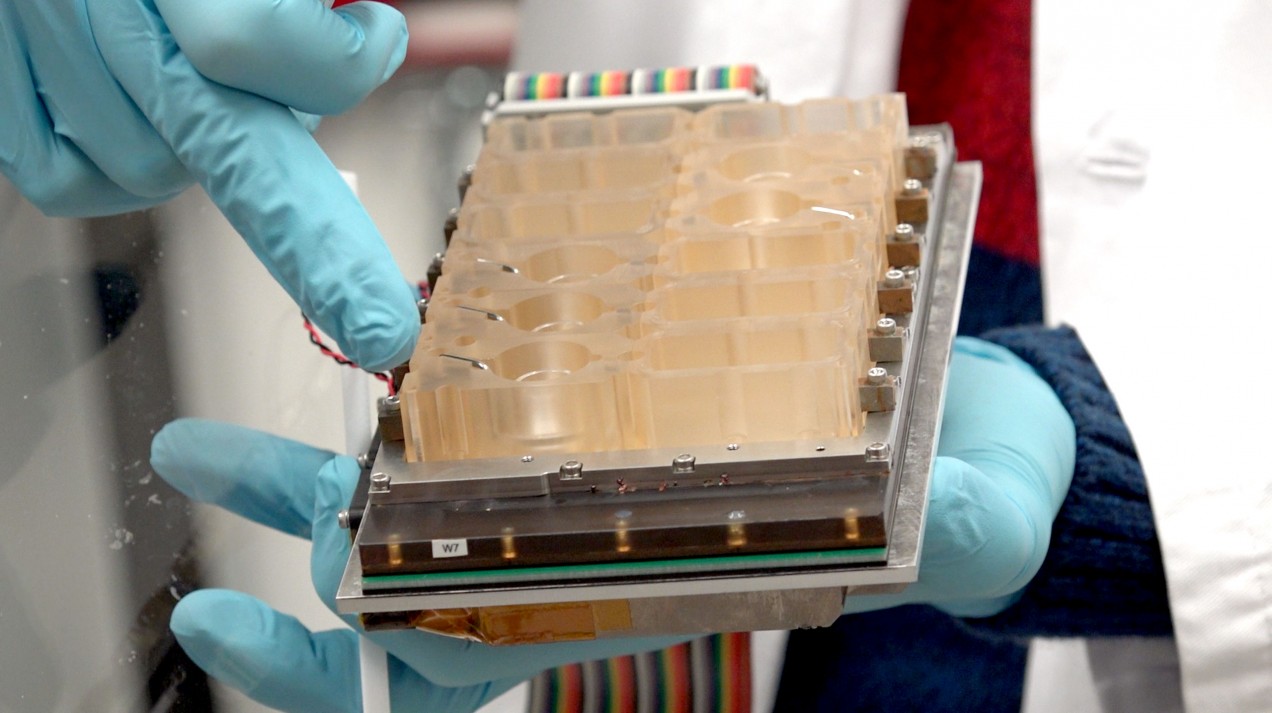

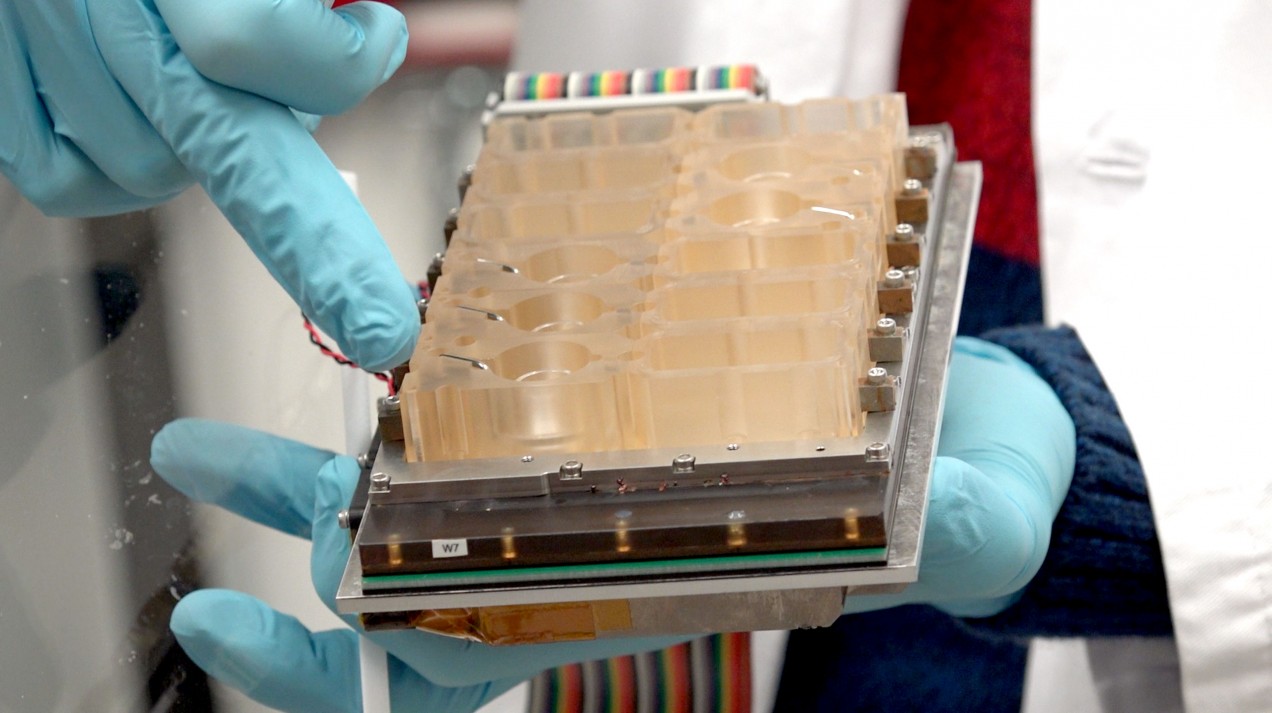

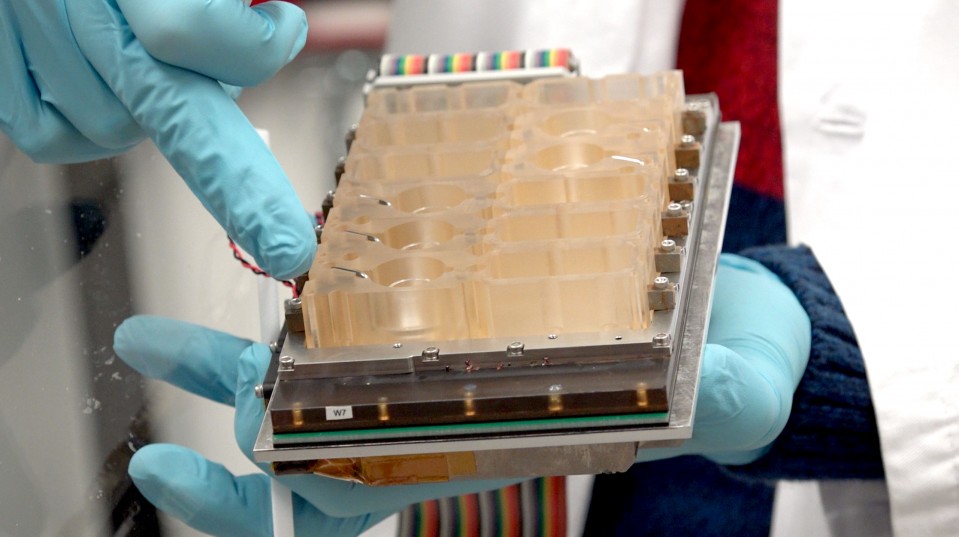

The device is about the size of a paperback book, with plastic compartments designed to mimic a woman’s ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and liver. Evatar has real human cells in it, obtained from women undergoing surgery for other reasons. A mini-liver was included because that’s the organ that metabolizes drugs.

Scientists at Northwestern University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Draper Laboratory, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, say they built Evatar by growing each tissue type in its own plastic compartment, connecting them with a network of tiny tubes. Twenty electric micro-pumps circulate a blue cocktail of nutrients and hormones, which serves as a blood substitute and lets the tissues communicate.

To test whether the chip could ovulate, the researchers added a mouse ovary (human ovaries aren’t easy to obtain). Within 14 days, according to their report in Nature Communications, the ovary released an egg.

Teresa Woodruff, a reproductive scientist at Northwestern University who led the project, says her team is also working on a male version. It may eventually also be possible, she says, to take tissue samples from any woman and, using stem cells, create a “personalized Evatar.”

With Evatar, scientists have come a little closer to creating an entire “body-on-a-chip” that could simulate a person’s physiology. Jonathan Coppeta, a biosystems and tissue engineer at Draper, says the artificial menstrual cycle might let drugmakers safely explore new contraceptives or test treatments for diseases like fibroids, endometriosis, and cervical and ovarian cancers. “Historically, women’s physiology has been underrepresented in the drug development pipeline,” he says.